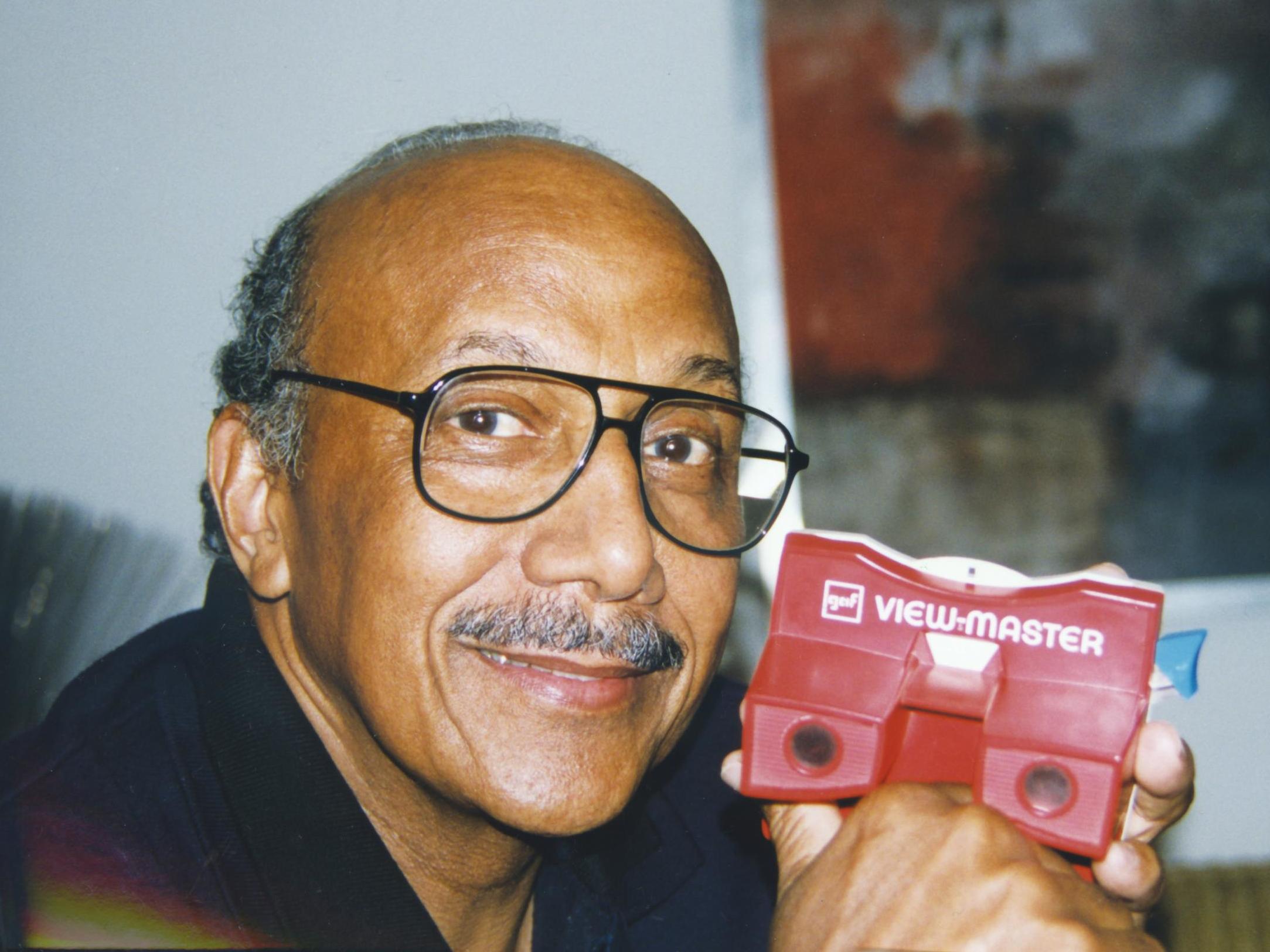

Charles Harrison: Designer whose refashioning of the View-Master made it a popular toy

As chief product designer for Sears, he oversaw the design of hundreds of products, blazing a trail for African-Americans in the process

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Charles Harrison first interviewed for a job at Sears, Roebuck and Company in the mid-1950s, he was told they would not hire him because he was black. Five years later, he became the company’s first African-American executive.

The industrial designer, who died aged 87, would go on to work for Sears until his retirement, rising to oversee the company’s design group and helping create more than 700 consumer products including the first plastic dustbin – polypropylene products had only been cast in small moulds until that point.

Charles Harrison was born in Shreveport, Louisiana. His father Charles Harrison Sr taught industrial arts at Southern University. His mother Cora Lee was a housewife with a love of nature and a talent for making a beautiful home. Harrison credited them both with inspiring his passion for design.

During his childhood, the family moved to Texas and then Arizona for Harrison Sr’s work. In Arizona, Harrison attended an all-black high school, the George Washington Carver High School, which closed during integration. Upon leaving school, Harrison earned his bachelor of fine arts at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, which is where he met his future wife, Janet Eleanor Simpson.

After graduation, Harrison was drafted into the army. He served in Germany for two years, working as a cartographer. When he was back in the US, he took a masters degree in art education at the Illinois Institute of Technology. It was at this point that Harrison first interviewed at Sears, only to be told that he would not be hired because of the colour of his skin.

However, Carl Bjorncrantz, who had interviewed Harrison, was impressed enough to give him freelance work for the firm on the side. This Harrison undertook alongside his first full-time job, which came courtesy of his former professor, Holocaust survivor Henry P Glass. The Viennese designer abhorred discrimination and ensured that Harrison’s talent was recognised.

It was while working at Robert Podall and Associates that Harrison first made his mark on the design world. In 1958 he oversaw an update of the View-Master’s clunky 1938 design, turning the 3D transparency viewer, which up until then had been largely confined to professional use in photographic studios, into a must-have toy by remodelling it in lightweight red plastic. Importantly for Harrison, who was dyslexic, his new View-Master was so instinctive to use that it required no complicated instructions – simplicity informed all of the 750 things he designed.

In 1961, two years after Harrison successfully relaunched the View-Master, Bjorncrantz called to say that he was in a position to offer Harrison a job at last. In an interview for Aileen Kwun and Bryn Smith’s 2016 design book Twenty Over Eighty, Harrison described how he reacted to the development.

“I just took it in stride,” he said. “I see it as a parallel to Nelson Mandela’s life under apartheid, for example, where he was put in prison and then one day he became president of the company. That’s how I feel about it… Ultimately, I think they decided it was time to make some effort to show that Sears was not so rigid or mean-spirited.”

He added: “That was just life in America. A lot of that racism still exists. It was understood clearly that African American people were on the outside of American culture… I accepted it as the way life was going to be, and that I’d have to learn to negotiate. And I did.”

Harrison’s design work for Sears had incredible breadth. He worked on everything from toys to sewing machines to power tools. His use of materials was particularly innovative. He revolutionised the heavy old sewing machine by casting it in lightweight aluminium. However, his personal favourite design triumph was the first plastic dustbin.

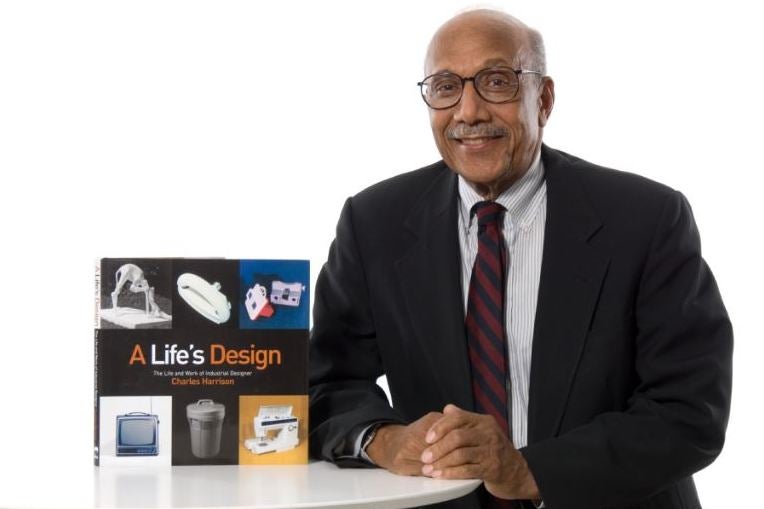

The project was inspired by Harrison’s frustration with the terrible racket metal dustbins made as they were emptied into the refuse truck. He wrote in his 2005 memoir, A Life’s Design that “as an industrial designer, your audience is neither history nor fame but a couple who worked hard to buy their first home on a quiet street and would love just one more hour of sleep in the morning, even on trash day”.

After retiring from Sears in 1993, Harrison took a part-time teaching position at his old alma mater, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He also taught part-time at the University of Illinois and Columbia College. He published his memoir in 2006.

In 2008, Harrison’s invaluable contribution to industrial design was recognised when he became the first African American to receive the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum’s lifetime achievement national design award. Meanwhile, George Washington Carver High School became a museum and cultural centre, with a room dedicated to showcasing his work.

Harrison said what ultimately motivated him to design so many things throughout his career was “the challenge of improving something, and making people smile” and “making life better for people – for humanity”. As he did with those quiet dustbins.

Harrison is survived by his son, also called Charles, and two grandchildren.

Charles “Chuck” Harrison, American industrial designer, born 23 September 1931, died 29 November 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments