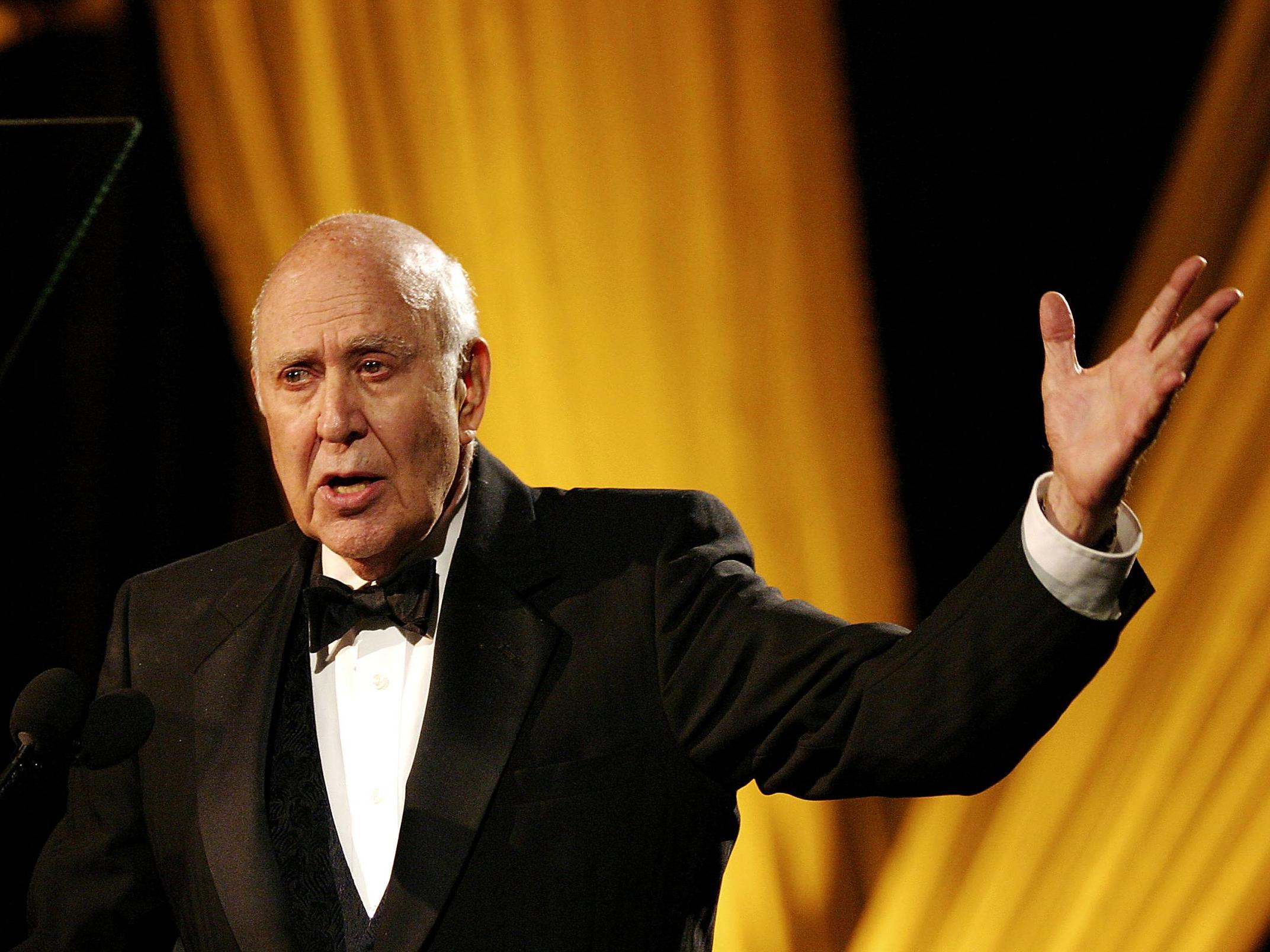

Carl Reiner: Giant of American comedy who didn’t need the spotlight

Often playing second fiddle to bigger names, the actor, writer and producer played a major role in the careers of Sid Caesar, Steve Martin and Dick Van Dyke

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Carl Reiner was one of the most influential and prolific figures in post-war American comedy, writing, producing, directing and acting over seven decades.

In a career rich with distinction, one would have to single out his eight-year association with Sid Caesar in the 1950s, the long-running Dick Van Dyke Show, which he produced, wrote and appeared in throughout the 1960s, and the four films he later directed with Steve Martin – The Jerk, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, The Man with Two Brains and All of Me.

Born in the Bronx district of New York, where his father worked as a watchmaker, Reiner found employment at 16 as a machinist’s helper in a millinery factory. He was also accepted for free evening classes at drama school, and quickly found himself cast in a jazzed-up version of The Merry Widow.

Years later he turned the experience of combining a boring day job with an exhilarating nightlife into an autobiographical novel, Enter Laughing, which went on to be adapted for the Broadway stage in 1963.

At the start of the Second World War, Reiner entered the signal corps and teamed up with another future American comedy star, Howard Morris, with whom he subsequently toured the Pacific for 18 months in GI revues. After his discharge in 1946, he landed the leading role in a touring production of Call Me Mister, and appeared in the Broadway musical Alive and Kicking.

His big break came in 1950 when he was spotted while working as a stand-up comic in the Borscht Belt in New York State by the producer Max Liebman, then putting together the young team that would support the great post-war comedy find, Sid Caesar, in Your Show of Shows. Reiner became Caesar’s lead stooge or straight man. Much as he admired Caesar’s talent, Reiner preferred to hang out with the show’s writers, who included Mel Brooks and Neil Simon, and began contributing ideas for sketches.

While he never received any credit for his writing efforts on Your Show of Shows, or the subsequent Caesar’s Hour, Reiner received the first of eleven Emmy Awards, in 1956, for his work as supporting comedy actor to Caesar.

Away from the cameras, Reiner also became the straight man to Mel Brooks, whose gift for improvisation was known only to a small circle of friends and workmates at the time. As a double act, they became the most popular party guests in Manhattan, performing unscripted sketches at the drop of a hat.

One of these, The 2,000-Year-Old Man, was eventually recorded and fashioned into an animation. What started out as an after-dinner turn at Reiner’s house in New Rochelle became a minor American cult in the 1960s. Reiner would introduce Brooks as “a man who was present at the crucifixion of Jesus Christ”, then ask leading questions about his life and times. With their combined comedy talents, Reiner and Brooks managed to walk a fine line between inspiration and sacrilege.

In 1958, after Sid Caesar’s third and final series was cancelled, Reiner spent the summer writing the first 13 episodes of Head Of The Family, a semi-autobiographical sitcom featuring the exploits of a comedy writer, Rob Petrie, intending it as a vehicle for himself. The pilot didn’t find any takers but CBS producer Sheldon Leonard thought it could work with a bright young comedy star named Dick Van Dyke in the lead.

Once again it meant another talent taking the lion’s share of the credit, but since he was the show’s writer and producer, as well as playing Alan Brady, Petrie’s egotistical TV star boss, Reiner knew his work would be acknowledged by those who mattered. It also made him extremely rich. The Dick Van Dyke Show, which also starred Mary Tyler Moore as Petrie’s wife, enjoyed five series and became the first sitcom to address the question of balancing family life with the workplace.

In the 1970s, Reiner and Van Dyke returned with The New Dick Van Dyke Show, but Reiner was frustrated by the censorship increasingly imposed by CBS that he felt cramped the show’s sophisticated style. He walked off the show when CBS executives banned an episode in which one of Petrie’s children wandered into the bedroom while he was cuddling up to his wife.

Reiner had a parallel career in movies throughout the 1960s and 1970s, both as an actor (It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming, A Guide for the Married Man etc) and director (Where’s Poppa? Oh God! etc), and with the enforced demise of his professional association with Dick Van Dyke, he linked up with the up-and-coming Steve Martin to make a series of acclaimed comedy classics.

In the underrated Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, filmed in black and white, Reiner contrived to have Martin’s 1940s private eye interact with stars such as Ingrid Bergman, Humphrey Bogart and Ava Gardner, using cleverly interposed scenes from pre-war film noir classics. Reiner himself contributed a cameo as a psychopathic Nazi.

In 2003, Reiner published a memoir, My Anecdotal Life, recalling amusing incidents from his long career, including the time he captivated Sidney Bechet and his band by reading them Kafka’s Metamorphosis during a thunderstorm in the Catskill Mountains in 1942.

In recent years he starred as Saul Bloom in the Ocean’s Eleven series and appeared in documentaries such as Broadway: Beyond the Golden Age and If You’re Not in the Obit, Eat Breakfast. The latter’s title was inspired by his morning ritual. “Every morning before having breakfast,” Reiner said in the film, “I pick up my newspaper, get the obituary section and see if I’m listed. If I’m not, I’ll have my breakfast.”

Of his lifetime of playing second fiddle to bigger names, Reiner once said, “I used to aspire to be the top banana until I realised how good a second banana I am. I have the facility to appreciate all kinds of comedy and to herd it in the right direction when it is not focused enough.”

Carl Reiner, actor, born 20 March 1922, died 29 June 2020

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments