The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

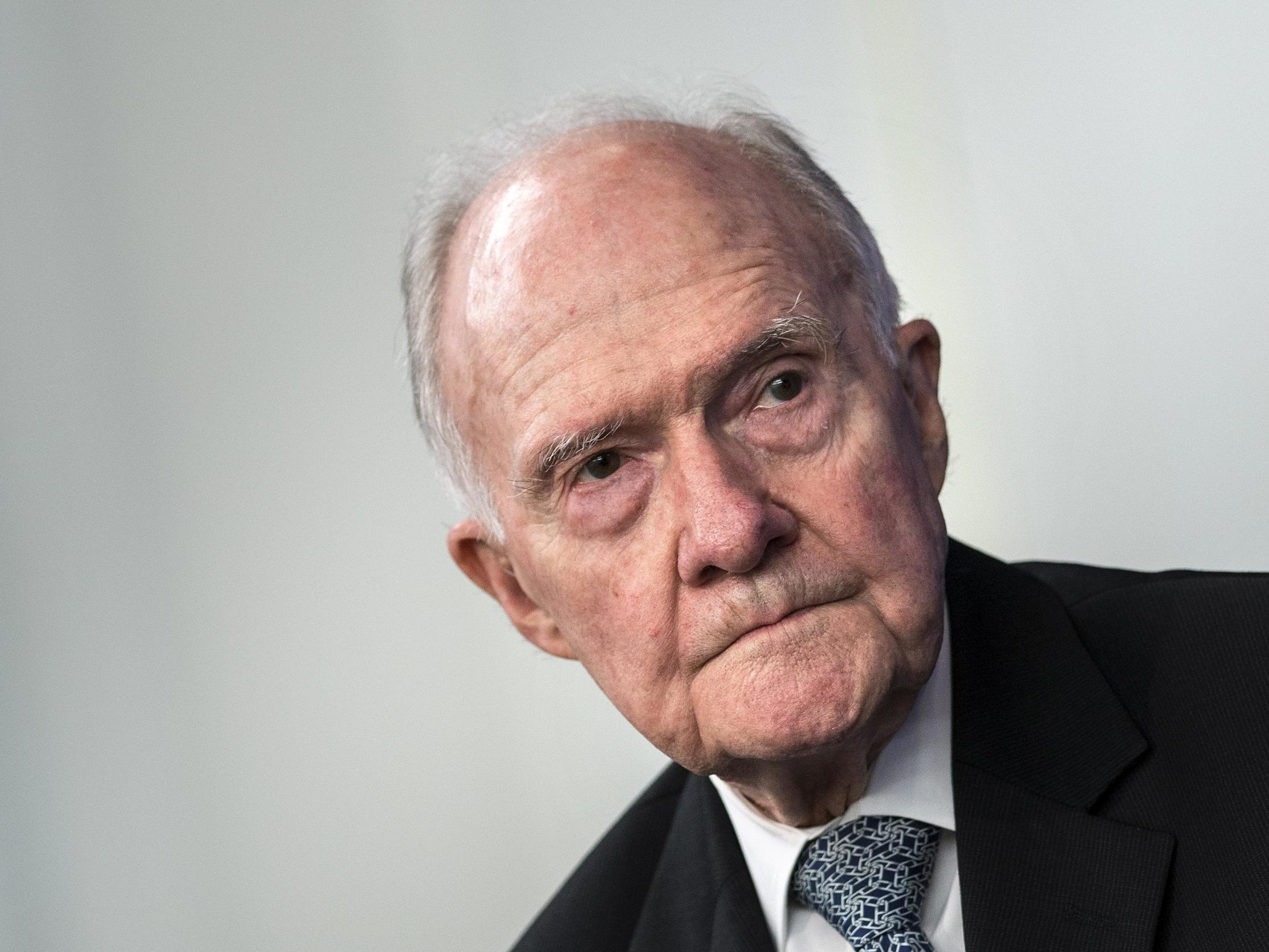

Brent Scowcroft: Pragmatic national security adviser to George HW Bush

Above all, he was a ‘realist’ who believed America should accept the world as it was

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Brent Scowcroft was arguably the most effective US national security adviser since the post was created in 1953. His mentor Henry Kissinger might have surpassed him for gravitas. But measured by deftness, cool judgement, and the ability to preserve smooth relations between the often warring arms of the US national security apparatus, Scowcroft’s performance between 1989 and 1993 under George HW Bush set the gold standard.

He was above all a pragmatist, a “realist” who believed America should accept the world as it was and not seek to impose transformation through grand gestures and messianic ideas. “I believe in the fallibility of human nature,” Scowcroft told The New Yorker magazine in 2005. “We continually step on our best aspirations. We’re humans. Given a chance to screw up, we will.”

Like the first President Bush, with whom he had the closest of personal friendships, Scowcroft did not do “the vision thing”. Soft-spoken, at times almost gentle, but tenacious in his ideas, he was above all a manager of global affairs. He advocated the first Gulf war simply because he believed that Saddam Hussein’s invasion and occupation of Kuwait could not be allowed to stand, for geostrategic reasons. Equally firmly however, he believed that when Kuwait had been liberated in February 1991, America should not go all the way to Baghdad.

“At the minimum, I believed we’d be an occupier in a hostile land,” he said years later, summing up the central problem the second President Bush would encounter in 2003. And once there, Scowcroft argued back in 1991, how would the US extricate itself? “I don’t like the term ‘exit strategy’ – but what do you do with Iraq once you own it?”

He was thus a forthright opponent of Operation Iraqi Freedom, and of the “utopian” neo-conservative dream of bringing democracy to the Middle East. Fiercely proud of the elder President Bush’s coalition-building in 1990 and 1991, he was also appalled by the go-it-alone, my-way-or-the-highway approach of the younger.

In August 2002, Scowcroft set out his objections in The Wall Street Journal, with an op-ed piece entitled “Don’t Attack Saddam”. For critics of the war, a foreign policy grown-up was finally speaking out. But he was accused by old colleagues of rocking the boat – among them Condoleezza Rice, the then national security adviser whose talent Scowcroft had first spotted and nurtured, but who was furious at the perceived disloyalty. Most embarrassing for the White House, there was a strong sense that the father’s most trusted retainer was speaking for the first President Bush, who obviously could not criticise his son directly.

Brent Scowcroft was born in Utah in 1925, a Mormon who all his life neither smoked nor drank. After graduating from the US Military Academy at West Point near the top of his class in 1947, he entered the then Army Air Corps, because “all my friends were joining”. His flying days however ended when he broke his back in a training accident and was hospitalised for two years.

Instead, Scowcroft returned to West Point to teach Russian history, before taking a series of staff jobs at the Pentagon. Among the assignments was a stint as deputy air attache at the US embassy in Belgrade between 1959 and 1961, where he was first confronted by the enduring power of nationalism. “I don’t remember ever hearing people call themselves Yugoslavs,” he would remember, “They always called themselves Serbs, Croats, Slovenians.” Decades later, the experience would shape the initial hands-off reaction of the US as the Balkan wars exploded in the early 1990s.

Scowcroft might have continued to toil in relative obscurity, had he not in 1972 caught the eye of Henry Kissinger, who then combined the posts of secretary of state and national security adviser, first under President Nixon and then briefly in the Ford administration. Scowcroft became Kissinger’s deputy as national security adviser, and then took over the job himself in 1975 when Kissinger returned full time to the State Department. Modest and unassuming, he lacked Kissinger’s deviousness, bombast and self-importance. But as a back-stage operator who could be trusted absolutely, he quickly made his mark.

When Jimmy Carter defeated Ford, Scowcroft found himself on the sidelines – and generally remained there even when Ronald Reagan recaptured the White House for the Republicans. Scowcroft the cautious pragmatist was out of step with Reagan the idealist; he was predictably sceptical about Star Wars, and disapproved when Reagan labelled the Soviet Union the “evil empire”.

But under George HW Bush his talents found a perfect setting. The two men’s friendship went back to the mid-1970s, when Scowcroft was national security adviser for the first time, and the future president was director of the CIA. Not only were their world views virtually identical, they shared a deep and genuine affection. As president, Bush Sr would set up the “Scowcroft Award”, for the senior official who fell asleep most obviously during meetings. Scowcroft “earned the award the old-fashioned way”, Bush would write, “he slept and slept in trying situations”.

Indeed the tougher the going, the cooler was Scowcroft. The first Bush administration had to deal with some of the most momentous events of the 20th century; not just the 1991 Gulf war, but the collapse of communism, the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the reunification of Germany, as well as the Tiananmen Square massacre in China, and the outbreak of war in the Balkans. By and large the cautious approach was vindicated.

The relative inertia on Yugoslavia might be seen as a failure of realism. On the other hand the peaceful end of the Soviet Union – without war, indeed with almost no loss of life – was in part thanks to the sensitive, non-triumphalist diplomacy of the White House. Seen through the prism of America’s various and mostly self-inflicted disasters in the Middle East, the 1998 memoir by Scowcroft and the elder Bush, entitled A World Transformed reads as a manual of statecraft.

But Scowcroft found himself almost a dissident, as another Bush became president. His own views hadn’t changed, he would remark, but those of many old friends had – and none more so than Dick Cheney, the vice president with whom he worked closely in the Ford and first Bush administrations, the pragmatist now turned grim ideologue. “I consider Cheney a good friend – I’ve known him for thirty years,” Scowcroft said. “But Dick Cheney I don’t know anymore.” During George W Bush’s first term, Scowcroft chaired the Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, a body supposed to offer impartial counsel to the president. Alas, on the decisions that really mattered, he was never consulted.

Brent Scowcroft, US national security adviser, born 19 March 1925, died 6 August 2020

Rupert Cornwell died in 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments