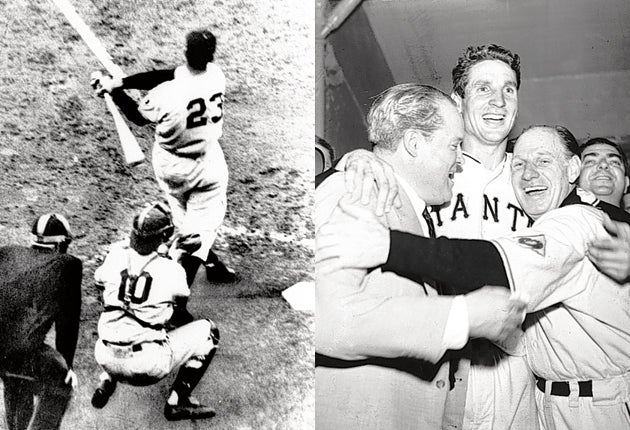

Bobby Thompson: Baseball player who hit ‘the shot heard round the world’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For most students of history, the "shot heard around the world" is either the one at Concord, Massachusetts in 1775 that started the American War of Independence, or the one that killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914. But for baseball fans it means something else: the most famous home run of all, hit by Bobby Thomson to win the National League pennant for the New York Giants in 1951.

In fact, the author of this American legend was not a native-born American at all. The son of a Glasgow cabinetmaker, Thomson arrived in the US when he was two, following his emigrant father. At high school, he showed a talent for the national pastime of his adopted country and was signed up by the Giants at the age of 18. On the afternoon of 3 October 1951 came his date with destiny.

It was the decisive third game of the NL play-off between the Giants and their bitter rivals the Brooklyn Dodgers, at the Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan – the first sporting event to be telecast live from coast to coast. Thomson came up to bat at the bottom of the final ninth inning, with the Giants behind 4-2, and smashed a three-run homer on the second pitch he saw.

The epic blow, rounding off a regular season in which the Giants at one point late in the season trailed the Dodgers by 13 games, completed a comeback out of the pages of Boy's Own magazine. "I don't believe it, I don't believe it, I don't believe it," screamed the Giant's radio commentator Russ Hodges.

In the New York Herald Tribune the next day, the great sportswriter Red Smith elevated the moment to universal significance. "Now it is done," he wrote, "Now the story ends. And there is no way to tell it. The art of fiction is dead. Reality has strangled invention. Only the utterly impossible, the inexpressibly fantastic can ever be plausible again."

Over the years, the homer moved beyond journalistic hyperbole to enter 20th century myth. The old Polo Grounds have long since vanished beneath high-rise apartment blocks, and within a few years of Thomson's feat the Giants had moved to San Francisco and the Dodgers to Los Angeles.

Thus the moment turned into a sepia symbol of a vanished and less complicated age, a time of post-war prosperity, when major league baseball was played on midweek afternoons and New York seemed to rule the universe. The fact that the home-run ball, the Holy Grail of baseball collectors, was never found only added to the legend.

In his celebrated novel Underworld Don DeLillo uses the lost ball as a thread of memory. The home run cropped up in the movie The Godfather, and in an episode of M*A*S*H. In 1999 the US post office issued a stamp commemorating the event.

Inevitably, Thomson's subsequent career was an anticlimax, though he hit a more than respectable total of 264 homers before he retired in 1960. A reserved and modest man, he then became a salesman for a paper products firm – but all anyone wanted to hear about was The Home Run. As the years passed, he and Ralph Branca, the Dodgers pitcher who threw the strike that Thomson dispatched into the Polo Grounds' left-field stands, appeared together at baseball dinners and memorabilia sales. Bound together by an accident of sporting history, they became firm friends. And Thomson never lost his sense of proportion. "It was just a home run," he would say, "It was just a home run."

Rupert Cornwell

Robert Brown Thomson, baseball player: born Glasgow 25 October 1923; died Savannah, Georgia 16 August 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments