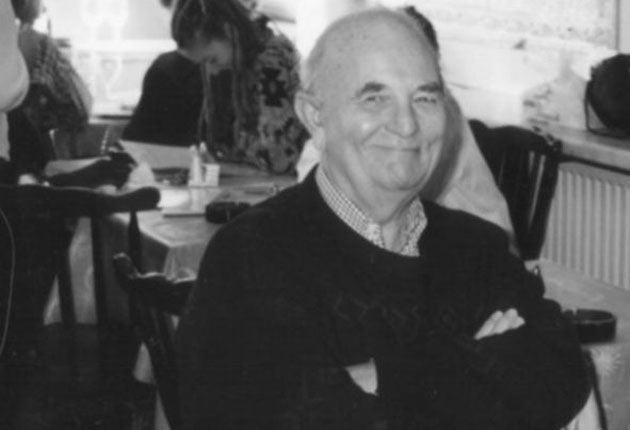

Bill Millinship: 'Observer' stalwart during the paper's golden age

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Bill Millinship spent almost all his distinguished career in journalism on the staff of The Observer. He was a key figure in the world's oldest Sunday newspaper in its golden age, which began when it published Khrushchev's "secret speech" of 1956, opposed the government during the Suez crisis and continued with its splendid coverage of the Hungarian uprising, its denunciation of apartheid in South Africa and its support for the ANC, and which lasted for a brief time after David Astor stepped down as its editor in 1975. Trevor Grove, editor of The Observer Magazine and later of the Sunday Telegraph said, "When I joined in 1980 Bill seemed to represent, along with a small band of colleagues like Terry Kilmartin and Michael Davie, the very soul of the old Observer, the keepers of the flame."

Like Kilmartin and Davie, Millinship not only embodied the institutional memory of the paper, but also was one of the guarantors of its integrity. "In those days the leader conference," Grove remembered, "was a cockpit of strong views, strongly held, as you might expect from a gathering of intellects that typically included Conor Cruise O'Brien, John Cole, Colin Legum, Neal Ascherson, Bill Keegan, Mary Holland and Katharine Whitehorn... and Tony Howard. Arguments could be long and fierce. Bill was a quietly stabilising and cohesive influence in these debates, for whose presence the editor, Donald Trelford, must have been deeply grateful." Bill was a taciturn man, with a flinty humour, and wry, smiling eyes that often betrayed his attempts to frown, but were capable of turning steely if someone was failing to do the right thing.

William Henry George Millinship was born in 1929 in Newport, South Wales, one of two children of a working class family. His father was a shipwright, and expected his son to join him working in the Newport shipyards, while his mother also worked. At St Julian's High School Bill played rugby (and was a member of what people still remember as "the invincible team"), went to concerts (he taught himself to play the piano) and acted (he was notable in Peer Gynt.) Millinship's younger sister Joyce, who survives him, said about him as a schoolboy that "he was like an alien, so brilliant and so intelligent."

His headmaster took an interest in this talented boy and had a word with a don at Keble College, Oxford, where Bill got a place on a State Scholarship. But first he did his National Service from 1947-49 in the RAF as a pilot (in later life he used these skills in gliding). At Keble he read English, ending up with a 2.1, and acted. A tutor at Keble told him that he thought there was a job available in Paris with the RTF, and Bill bravely packed his bag and went.

There he was befriended and mentored by Sturge Moore (son of the poet T. Sturge Moore and nephew of the philosopher G.E. Moore), who asked the young man if he could type. When Bill said no, Moore told him to "come back in six weeks when you can." He did – and got the job.

He had met Vera Zeale at a youth club in Newport when he was 14 and she a year younger, and in 1953 they married in Newport, but lived in Paris. Vera returned to Wales to have their eldest child, Julia, but their other three children were born in France. When taking her French driving test, Vera mentioned to the examiner that her husband was away, interviewing Brigitte Bardot. She was always convinced that she passed only because the examiner was so impressed.

Bill then worked in Paris for the BBC and stayed in France until 1964, reporting the Algerian War for the Observer as a colleague of Nora Beloff, and later as its Paris correspondent. Julia remembers him being away so frequently when they were children in Paris that they seldom saw him.

In 1964 the Millinships went to London and moved their four more or less French children into a house in Dulwich. (One son now is French, married to a French woman, and living in the Dordogne, near the house Bill converted for himself and Vera from an old barn.) Bill had returned to be news editor of the paper until, in 1969, he was sent to Washington.

It was a family joke that the biggest story happened when Bill was on holiday. He had to rush back to the office when the Watergate story broke in 1972 and when Nixon resigned in 1974. Returning to London, Millinship was foreign news editor, and was managing editor when I joined. He called me into his office at the end of 1980 when my column had won several prizes, and tried to look dour as he said, "I expect you'll want a rise, so I suppose we'd better put you on staff."

It was a slight surprise when, aged 59, Bill learnt Russian and he and Vera went to Moscow in late 1988. He retired from The Observer from Moscow in 1992, sending some of their household furniture to the Dordogne. In 1993 he published Frontline: Women of the New Russia, for which he had conducted extensive interviews with 31 women, some of whom had been privileged during the Soviet era. The blurb said: "this volume records the Neo-Stalinist who wants a return to the good old days, the apparatchik who has had 11 abortions, the seamstress who made Lenin's corpse a new suit every 18 months - women who have experienced great privilege and endured harsh living conditions, who witnessed great cruelty, and were fed colossal lies."

Many of the reviews were by academics, but even the most critical acknowledged the real value of the book in presenting, as one reviewer wrote, "a rich and interesting complement to qualitative studies of women in the new Russia." Bill's feminist sympathies were not surprising to those who knew how much he liked women and enjoyed their company. He began, but did not quite finish, work on another book, about Kate Marsden, an English nurse disliked by the nursing profession who travelled to a leper colony in Siberia in 1891.

Bill was interested in food, keen on and knowledgeable about wine, relished the theatre – and, said Julia, "many French artistes such as Piaf, Brel, Brassens, and Aznavour, whom he often saw perform in Paris. I remember him coming back from the Grand Old Opry, when he was Washington correspondent, with country music records including Crystal Gayle."

A rare disease, at first misdiagnosed at its onset in 2003, when Vera also learned she had breast cancer, marred Bill's last years. It turned out to be progressive supernuclear palsy (PSP), and meant he suffered from something like locked-in syndrome, able to communicate only by moving his hand, which meant he missed out being an active grandfather to his nine accomplished grandchildren.

Still he managed to indicate that he wanted to be taken back to France in October 2007; and also that he had wanted to attend the last hurrah of FObs – Friends of the Observer, an organisation of the paper's old guard, survivors of its golden age, scheduled to take place on 24 March.

Paul Levy

William Henry George Millinship, journalist and author: born Newport, South Wales 11 September 1929; Paris correspondent, Algerian War correspondent, Observer, to 1964; news editor, 1964-69; Washington correspondent, 1969-73; foreign news editor, 1973-1980; managing editor, 1980-1988; Moscow correspondent 1988-1992; married 1953 Vera Zeale (died 2008; two daughters, two sons); died Danbury, Essex 16 January 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments