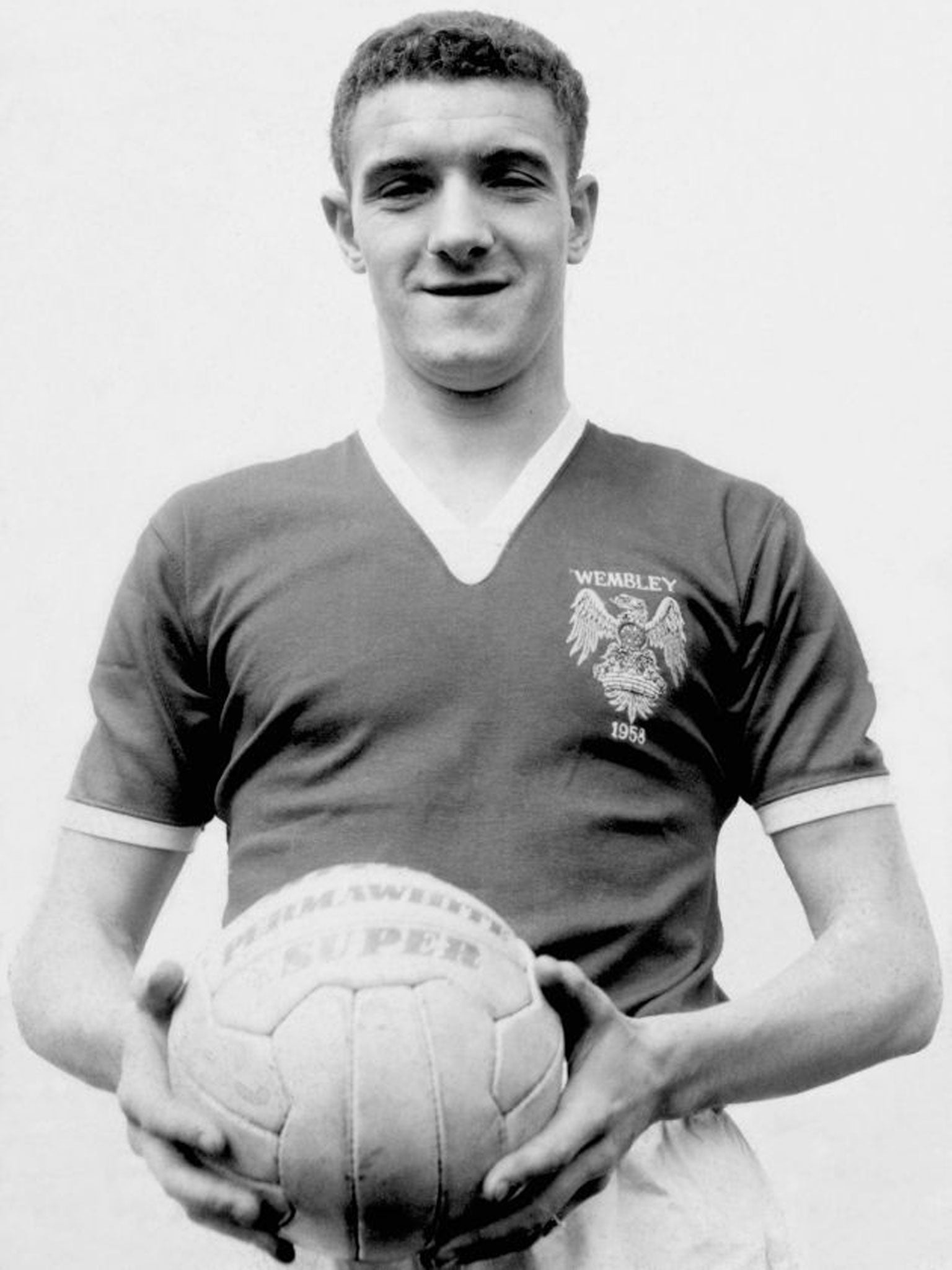

Bill Foulkes: Manchester United stalwart who survived the Munich disaster and went on to achieve European Cup glory under Matt Busby

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is scarcely possible to exaggerate the colossal stature of Bill Foulkes in the Manchester United story. A one-time miner and an extraordinarily hard man both physically and mentally, he grew up with Matt Busby’s “Babes”, the exuberant masterclass of English football who seemed destined to sweep all before them until calamity struck on a snowy runway at Munich airport in 1958.

He survived the crash of the Elizabethan airliner which claimed the lives of eight comrades, then played a seminal role in the rebuilding of the team before becoming the Red Devils’ granite-tough defensive cornerstone throughout the high-achieving 1960s. Verging on the realm of comic-book fiction, he confounded friend and foe alike by forsaking his customary back-line beat to surge forward and grab the semi-final goal against Real Madrid which lifted United to within touching distance of achieving their treasured, almost sacred ambition of lifting the European Cup.

Then finally, having become the old man of Old Trafford at the age of 36, along the way making more appearances as a Red Devil than any other footballer – since then his total of nearly 700 has been surpassed by only Bobby Charlton, Ryan Giggs and Paul Scholes – he was a key figure in the glorious denouement of his beloved club’s epic quest on a balmy evening at Wembley in May 1968 when Benfica of Portugal were beaten by four goals to one.

Foulkes hailed from a keen sporting family, his grandfather having excelled as a rugby league full-back for St Helens and England, and his father guarding New Brighton’s net during the Merseysiders’ spell in the Football League between the wars. However, despite being a natural at all ball games, the sturdy, rather stolid six-footer opted initially for the security of a mining job and when he turned professional with Manchester United in 1951, it was on a part-time basis.

Despite dividing his time between kicking footballs and man-handling coal trucks, he progressed rapidly through the junior ranks at Old Trafford, becoming part of the exhilarating youth revolution which was shortly to overturn the established order. The grittiest of realists, Foulkes recognised readily that he was not blessed with the extravagant natural talent possessed by most of his fellow rookies – the likes of Duncan Edwards, Eddie Colman and company – but it became steadily more apparent that his iron resolution and implacable aggression were valued hugely by manager Busby and his coaching staff.

For all that, as a callow reserve with no senior experience and besieged by gifted ball artists, he was fearful of the sack when he received a summons to the boss’s office in December 1952. Instead he was asked if he was fit for a top-flight debut at right-back against Liverpool and, after telling a little white lie – he concealed the pain of an injured ankle rather than miss his big chance – he ran out at Anfield for a searching direct confrontation with revered Scottish international Billy Liddell.

In the event, although Liverpool’s star winger grabbed an early goal, the newcomer coped manfully for the remainder of the match, inspired by the sage guidance of inspirational captain Johnny Carey, and United recovered to win 2-1. Busby was sufficiently impressed to let the flinty Lancastrian retain the No 2 shirt for the next fixture, but then his ankle problem ruled him out for the remainder of the campaign. Opportunity knocked again early in the following season and this time Foulkes made the right-back berth his own, performing with such consistent authority that he was handed a full England call-up to face Northern Ireland in October 1954, incredibly enough while still a part-timer.

Accordingly, after a shift at the pit he sailed for Belfast, where he acquitted himself competently in a 2-0 victory but was never selected for his country again. Years later, having enjoyed vast success as a centre-half, he would reflect ruefully that his only international chance had occurred when he had played only a handful of League games in a less-favoured position.

Still, the England experience emphasised to Foulkes, who had been loth to relinquish the long-term security of his colliery job, that his future lay in football, and now he bowed to long-term pressure from Matt Busby to go full-time. It was a decision that was to be vindicated handsomely as he thrived at club level in a precociously entertaining team which fired the imagination of the sporting world.

For all that, he was anything but a celebrity in the modern footballing sense, as illustrated by his mid-1950s experiences while completing his National Service in the Army. Unable to arrange permission to leave barracks on a regular basis, frequently he went absent without leave, disguising himself on train journeys to grounds all over the country in a successful attempt to avoid the military police. Thus, with the aid of a smart trilby, a voluminous overcoat and a briefcase, he played in 27 games during 1955-56, garnering a League Championship medal for his pains and amazing Busby by the single-mindedness, independence and audacity which underpinned his outwardly dour nature.

In 1956-57 there was another title, but also the bitter disappointment of FA Cup final defeat by Aston Villa. Had United won – which they had been favourites to do before being reduced to 10 men by the loss of their injured goalkeeper Ray Wood for most of the match – Foulkes would have been a member of the first club in the 20th century to land the elusive League and FA Cup double.

By then, the Red Devils were pioneering Britain’s path into European competition and in 1957-58 had qualified for their second successive semi-final when the team was decimated by the air disaster. Foulkes walked from the wreckage unscathed physically but suffering severe psychological wounds which would never leave him. However, he battled on as emergency captain as an under-strength United rode an emotional roller-coaster all the way to Wembley, where they lost the FA Cup final to Bolton Wanderers.

Thereafter Busby embarked courageously on radical team reconstruction and Foulkes was switched to his preferred role of centre-half. He emerged as one of the most dominant stoppers in the English game and struck up a formidable partnership with England notable Nobby Stiles, with Foulkes dominant in the air, the diminutive Mancunian more comfortable at ground level. Duly he helped to lift the FA Cup in 1963, League titles in 1965 and 1967 and, climactically, the longed-for European Cup in 1968.

That season, despite being closer to 40 than 30, and carrying a serious knee injury, Foulkes remained a veritable bulwark at the back, and he stunned manager, colleagues, opponents and fans by his derring-do in snatching the goal which scuppered Real in the European semi-final. His zero-tolerance policing of Benfica’s giant spearhead Jose Torres was crucial to United’s final triumph, after which he made only a few more appearances before making way for younger men.

Subsequently he became a successful coach, first at Old Trafford, then in the United States, Norway and Japan. Thereafter he returned to the Manchester area, passing on his expertise to local youngsters when well into his seventies, and remaining astonishingly fit for his age.

Bill Foulkes was never a star, exactly, and until he mellowed late in life, he was always something of a loner in the social sense, partly by inclination and partly due to spending his formative footballing years as a part-timer, thus missing out on opportunities for youthful camaraderie. But he was as straight as an arrow and Matt Busby knew he could rely on him – and did so for the best part of 20 years.

William Anthony Foulkes, footballer: born St Helens, Lancashire 5 January 1932; played for Manchester United 1950-1970; capped once by England 1954; coached Chicago Sting 1975-77, Tulsa Roughnecks 1978, San Jose Earthquakes 1980; Brynne, Stenjker, Lillestrom, Viking Stavanger, all Norway, 1980-88; Mazda Hiroshima, Japan 1988-91; married Teresa (two sons, one daughter); died Manchester 25 November 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments