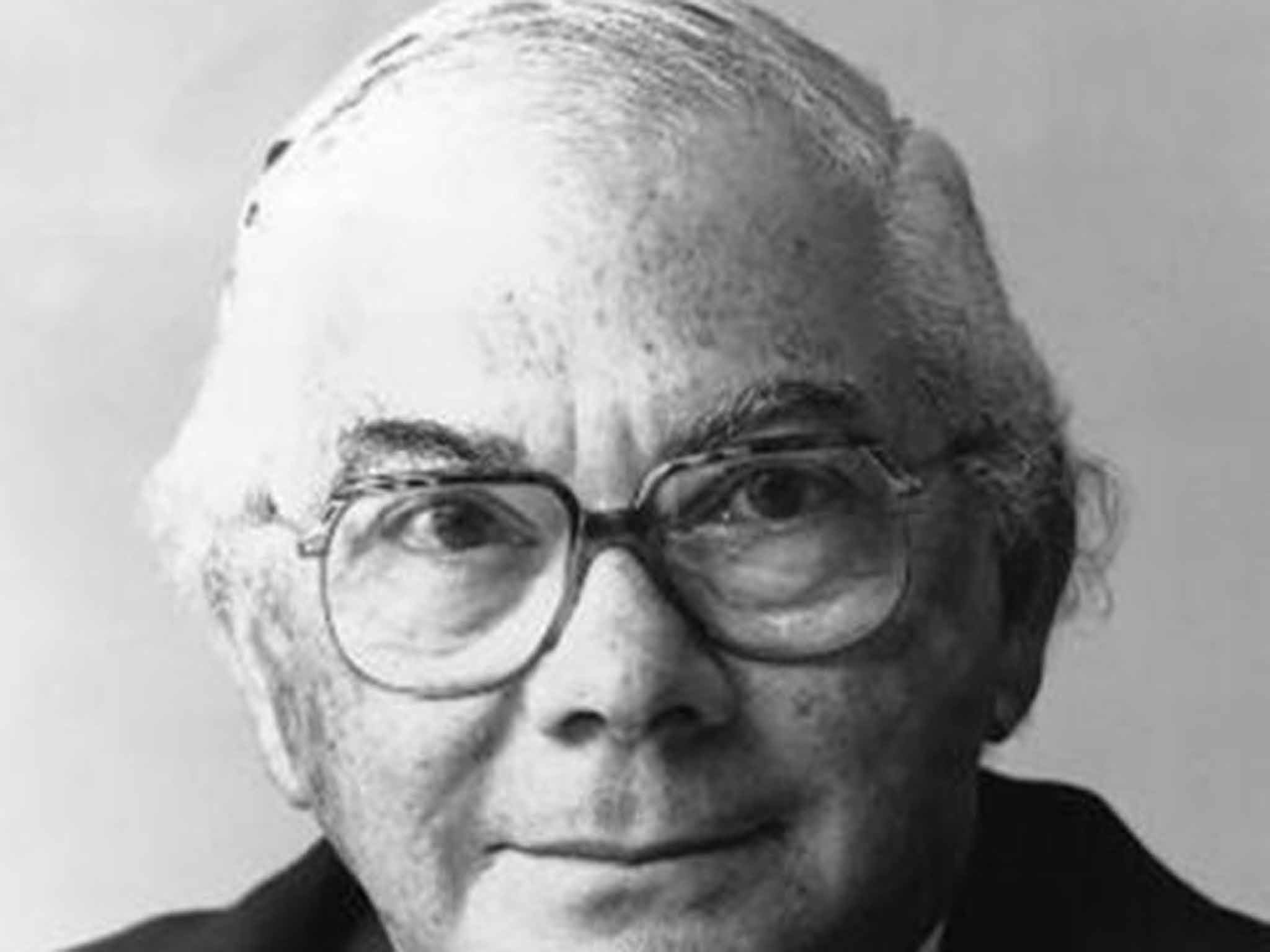

Bernie Leser: Shoe salesman who rose to become a much-loved executive in Condé Nast's 'Vogue' empire

A glad-hander to his shoulder blades, he knew everybody, dined all and sought always to engage with them personally

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Bernie Leser was the shoe salesman who lived out the dream of Arthur Miller's Willy Lomax in Death of a Salesman and achieved it all. The son of a Jewish German textile manufacturer, he fled Germany aged 14 for New Zealand, left school at 15 and rose as a magazine publisher with Condé Nast, launching Australian Vogue, heading the British company and finally becoming President of the US corporation in 1986.

His was a classic story of survival from the fate that befell the European Jews with the rise of Hitler. It was also a tale of the “provincial” from the Antipodes who succeeded through sheer hard work and a salesman's outgoing personality in reaching the top jobs in London and New York. A glad-hander to his shoulder blades, he knew everybody, dined all and sought always to engage with them personally.

Born in 1925 in Berlin, Bernie, or Bernd, as he was named, was brought up in Sondershausen, near Weimar, where his father, Kurt, ran a knitwear factory. His parents separated when Bernie, their only child, was three. His mother moved to Berlin after a scandalous liaison with a married man was revealed, while Bernie remained with his father and his extended family of aunts, cousins and grandmother in Sonderhausen.

He was saved from the Holocaust by an extraordinary coincidence. His father, Kurt, had been awarded the Iron Cross First Class for saving a fellow infantryman's life in the battle for Verdun. As the Nazi actions against Jews at home gathered pace in 1938, Kurt was contacted after nearly 30 years by the man whose life he had saved and who was now head of the Gestapo in the region. “Get out and get out quickly and I will help you,” was the message when the two met discreetly.

Two days later, Kurt left Germany. Bernie remained for six fraught months, excluded from his secondary school, moved to a Jewish boarding school and then driven from that when it was closed, the older boys being sent to Dachau and the younger left to fend for themselves. He finally fled, aged 14, with his aunt, uncle, cousin, grandmother and stepmother, helped again by his father's war companion.

Although many did get out in time, few countries made it easy for them to find refuge. Bernie's mother was only able to reach sanctuary separately through a connection in Bolivia. Bernie's family, reunited with his father, was one of the few who were able, through family relations of his aunt, to get into New Zealand, having failed to get into the US or Australia.

Bernie, like many of his compatriots, didn't speak much about his early life and only revealed the story in detail to his journalist son, David, for a book, To Begin to Know: Walking in the Shadows of My Father (2014), a work as much of personal expiation as biography.

In New Zealand and Australia, he found a region ready for his talents. Shedding his German language and name, and short of funds, he left school at 15 after less than two years. Studying business at night school, he tried his hand first at clothes cutting and design, for which he was ill-suited, and then as a salesman for shoes and clothes, for which he was.

The role launched him on an international career. At 22 he moved to Australia and married Barbara, daughter of the music publisher Howard Davis and an eminent concert pianist. In 1952 his company, HM Marler, sent him to Canada and in 1956 he went to London in a marketing role for Everglaze and Ban-Lon fabrics that took him all around Europe.

It was in London that he was approached, somewhat to his surprise, to launch an Australian edition of Vogue in March 1959. It took him back to Australia, where he became a citizen, and to a business he instantly embraced, with its mixture of eccentric fashionistas, endless gossip, high public profile and prestigious advertisers. With the creative help of an imperious and acerbic editor, Sheila Scotter – with whom he spectacularly fell out after five years – and against the predictions of many who said that Australians would never go for high-end clothes, he made Vogue Australia and a sister publication, Vogue Living, a success.

With a reputation for making businesses grow he was persuaded to become managing director of Condé Nast in Britain in 1976. It was a time of expansion and creative confidence. The Swinging Sixties had put London at the centre of the fashion and art worlds and Vogue was at its pinnacle. Bernie exuded bonhomie and optimism, increasing advertising and purchasing two new upmarket titles, The World of Interiors, edited by Min Hogg, and Tatler, then edited by Tina Brown. In 1979, as President of Condé Nast International, he launched German Vogue, speaking for the first time openly the language of his childhood.

Like Tina Brown, he moved to New York in 1986 when Si Newhouse, head of the Newhouse family's magazine businesses, appointed him President of Condé Nast's US operations. They were tougher times and a harsher corporate climate. Leser travelled tirelessly and helped launch two new titles, Condé Nast Traveler, edited at first by Harry Evans, Tina's husband, and Allure. But profits were harder to make and internal relations more fractious.

In the end the commercial forces of change encapsulated by the character of Howard Wagner in Miller's play came to the fore and Leser retired in 1994, tired and feeling that the world was turning away from him. The personal, engaging approach to business which he personified, was going out of fashion. Far more than just a glad-hander, he was incredibly kind to his staff. When an editor said she hadn't seen her Australian grandmother for more than five years, he thought up a business pretext to send her there. When an employee was going in for a serious operation, he rang the surgeon to ensure she was getting the best treatment.

In retirement, he returned to the Sydney which had always enthralled him, the books of biography which he devoured, his family and friends. His legacy was best summoned up by Jonathan Newhouse, chairman and chief executive of Conde Nast International. During his travels, Newhouse recalled, whenever he said he was from Conde Nast , even after a gap of some 20 years, the person would invariably say that they knew someone from the company. It was inevitably Bernie. “It seemed,” wrote Jonathan, “he knew everyone and they knew him, and they loved him.”

Berndt Leser, magazine publisher: born Berlin 15 March 1925; married 1952 Barbara Davis (one daughter, two sons); died Sydney 12 October 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments