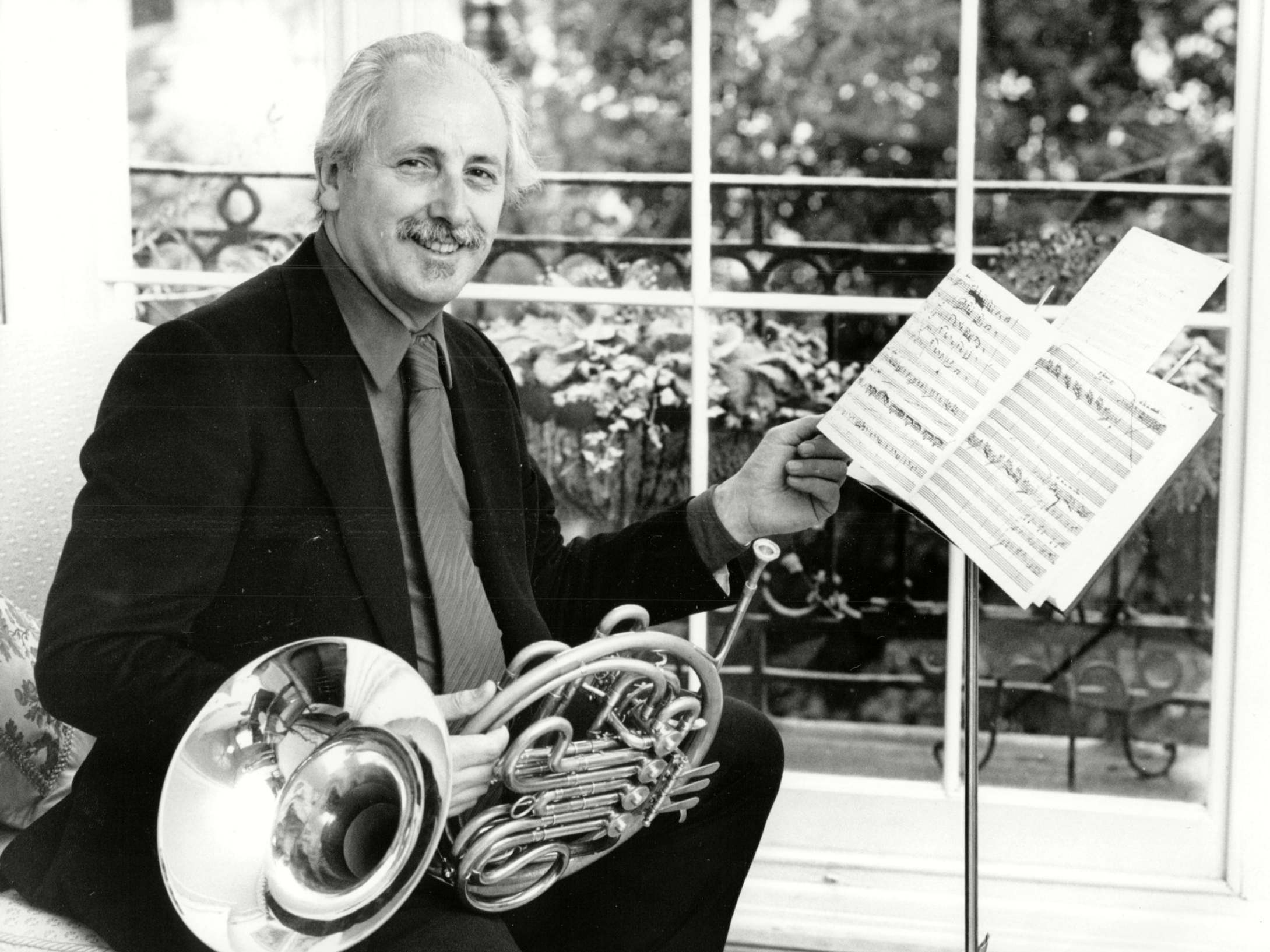

Barry Tuckwell: Pre-eminent horn player who became a star of orchestral music

His interpretations of Mozart and Strauss were dazzling, and he also stood out as a conductor

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Barry Tuckwell, who has died aged 88, rose to become the leading horn player of his time, a virtuoso who transformed the instrument’s place in the orchestra.

He was born in Melbourne, Australia, to Charles and Elizabeth Tuckwell in 1931. His sister, Patricia, was a violinist and one of a group of students at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music that included Charles Mackerras, the pianist Maureen Jones and Richard Merewether, who gave Barry his first lessons. His talent soon led him to play with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra at the age of 16 and with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra before he was 20.

In 1950 he came to England and pursued a career through the Halle (1951-3), the Scottish National (1953-4) and the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, from which he was headhunted in 1955 by the London Symphony Orchestra.

It was in poor shape: its finances were precarious and it had no chief conductor. But Tuckwell was one of a number of gifted young musicians – Gervase de Peyer and Neville Marriner were two others – who joined at this time. Soon elected to the orchestra’s board, in 1962 he became its chair, a position he held for five stormy years. “It was like sitting on a volcano. There was trouble almost all the time,” he recalled.

He clashed with the orchestra’s chief executive, Ernest Fleischmann, a brilliant entrepreneur and fundraiser who, in the board’s view, aspired to unreasonable influence in musical matters. In March 1967 Tuckwell resigned, stating that he could not work with Fleischmann. But Fleischmann was soon ousted and Tuckwell reinstated.

Despite these tensions, the period 1962-7 saw a sharp revival in the orchestra’s standards and status. Istvan Kertesz had been appointed principal conductor, Rozhdestvensky had accompanied Rostropovich’s marathon cycle of 31 cello concertos; Stokowski, Solti and Colin Davis had been among the guests who appeared with the orchestra on its first world tour in 1964.

Tuckwell asked the board to make him managing director, but this was rejected and in 1968 he left the orchestra after 13 turbulent but musically distinguished years. As principal horn he had displayed an iron nerve and, in the big solos of Strauss and Mahler, a snaring beauty of phrasing and sound (he played a Holton instrument with a large bore).

He now formed his own eponymous wind quintet and appeared at the Edinburgh Festival regularly between 1962 and 1992 (sometimes as a soloist), an astonishing span for a brass player. The year 1974 was characteristic: with the quintet he performed Danzi, Rossini and Schoenberg; with the Scottish National Orchestra, under the composer, he revived Thea Musgrave’s Horn Concerto, which he had premiered three years before in Glasgow’s Musica Nova series (he revived it again at the 1992 festival). He also championed works by Iain Hamilton, Alun Hoddinott, Don Banks and Richard Rodney Bennett, whose Sonata he premiered at the 1979 festival with the composer at the piano.

But it was the Mozart and Strauss concertos which were his daily bread. At the Proms, where he was a frequent soloist, he gave Strauss’s Second Concerto, in 1984, with Charles Mackerras and the Australian Youth Orchestra. Between 1970 and 1995 he regularly toured in the country of his birth. Tuckwell’s faultless virtuosity is apparent in no less than four recordings of the Mozart concertos, in Strauss and in a number of 20th-century works.

Made an OBE in 1965, he was president of the International Horn Society from 1969 to 1977 and again from 1992 to 1994. Professor at the Royal Academy of Music from 1963 to 1974, he was appointed Hon RAM in 1966. He edited much horn literature for Schirmers and published two books: Playing the Horn (1978) and The Horn (1981).

He also had a secondary career as conductor of the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra (1979-83) and of the Maryland Symphony Orchestra (1982-98). No doubt he kept in mind, in these roles, the advice he had once given to Andre Previn: “When you do a piece that is terribly complicated, if you ever get lost, just look vague and elegant and we’ll fix it. If you start flapping at us, we’re all sunk.”

He was married three times (to Sally Newton in 1958; Hilary Warburton in 1971; and Susan Levitan in 1992) and had three children.

Barry Tuckwell, musician, born 5 March 1931, died 16 January 2020

Robert Ponsonby died in 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments