Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

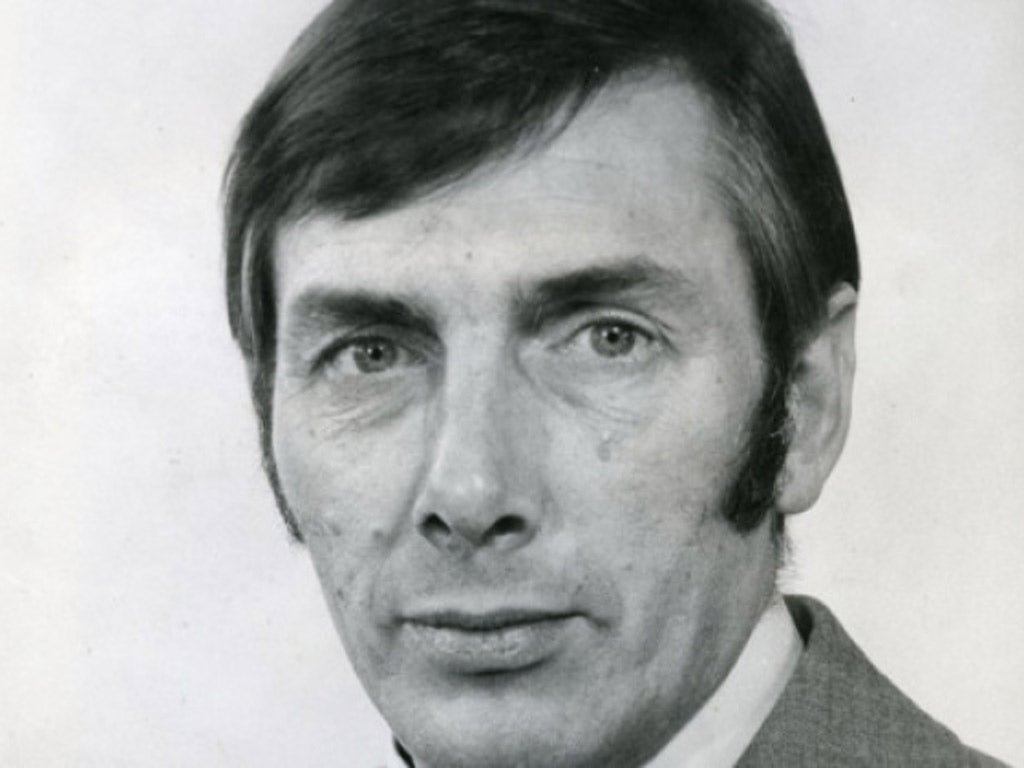

Your support makes all the difference.When Barry Askew arrived in Fleet Street to rescue the ailing News of the World, his star was in the ascendancy. Eight months later his future was all behind him. His brief stewardship proved to be one of the shortest editorships in journalistic history.

Spending his formative years in the Peak District, Barry Askew wanted to become a professional footballer, but at 16 became a trainee on the Derbyshire Times. Five years later he moved to the Sheffield Telegraph before an invaluable apprenticeship with Raymonds News Agency, based in Derby.

His editorial career began in earnest in 1961, with a not entirely untroubled stint at the Matlock Mercury. He went on to edit the Sheffield Morning Mercury and Sheffield Star before moving to Preston in 1968 to take charge of the Lancashire Evening Post. Over 13 years Askew turned this somewhat venerable daily broadsheet into a vibrant and successful campaigning newspaper.

On taking over, he became aware that all was not well at nearby Whittingham Hospital, then one of the largest mental hospitals in the country. Increasingly desperate claims of overcrowding, understaffing, racketeering, cruelty and even murder were ignored or suppressed by the hospital's management committee. Askew's campaign helped turn the institution on its head and ultimately brought about national reform within the mental health sector.

He went on to serve on the Davies Committee, set up in the wake of the Whittingham affair to reform hospital complaints procedures. His crusade brought him the 1971 National Press Awards Campaigning Journalist Award. Further honours would follow, most notably for his pursuit of Stanley Parr.

In July 1976, a Blackpool police officer, Harry Roby, made a formal complaint about Lancashire's Chief Constable during the annual inspection of the force. A subsequent report by Sir Douglas Osmand, then Chief Constable of Hampshire, outlined 37 charges against Parr. They included misuse of police manpower, showing favour to individuals, falsifying documents, intervening to reduce criminal charges and securing preferential treatment for motorists accused of speeding and parking offences.

With the County Council trying desperately to keep the matter under wraps, all would have remained secret had Askew, in February 1977, not published the charges in full. Suspended a month later, Parr was dismissed that December. Askew produced a damning 50-page dossier outlining further allegations of corruption then seemingly endemic at all levels of local government.

In 1979, a phone call intended for Askew and recorded by a receptionist at the paper's Fishergate headquarters created national headlines. Purporting to be the Yorkshire Ripper, aman with a Wearside accent referred to the unsolved murder of Joan Harrison, murdered in a derelict Preston garage in 1975. Seriously wrong-footing the police hunt, the phone call was later found to be a hoax. In 2006, a 49-year-old unemployed man, John Humble, was convicted of perverting the course of justice.

Alongside his newspaper work, Askew was also forging a successful career on radio and television. A regular contributor to regional news programmes, he also regularly presented Granada Television's What the Papers Say. Arriving in Fleet Street in April 1981, he was by then the archetypal hard-drinking, hard-living hack, soon to be lampooned by Private Eye as "The Beast of Bouverie Street".

With circulation of the News of the World in free-fall, his bold launch of a colour magazine quickly reversed the decline. However, behind the scenes he was enduring an increasingly fractious relationship with the paper's owner Rupert Murdoch. Matters soon came to a dramatic head over Sonia Sutcliffe, wife of the Yorkshire Ripper. Askew thought he had successfully negotiated a successful deal for her story, but suddenly the Murdoch coffers clanged firmly shut.

In December 1981 he was one of several editors invited to Buckingham Palace after Princess Diana had been hotly pursued by photographers when popping out of Highgrove to buy some wine gums in Tetbury High Street. His host had expressed her sadness that her daughter-in-law was being unduly harassed by the press, "With respect Ma'am, don't you think it would be a good idea if she sent a servant out for the wine gums instead of going herself?" Askew rather unwisely observed. "That is a most pompous remark, Mr Askew," responded the Queen before quickly moving on.

Rupert Murdoch was also not amused. Within a week, Askew had gone. Thereafter, not always in the best of health, while fronting a Lancashire cable television company, he also edited a number of Fylde Coast free sheets.

Kenneth Shenton

Barry Reginald William Askew, journalist: born Basford, Nottinghamshire 13 December 1936; married firstly June Roberts (one son, one daughter), secondly Deborah Parker; died Broughton, Lancashire 17 April 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments