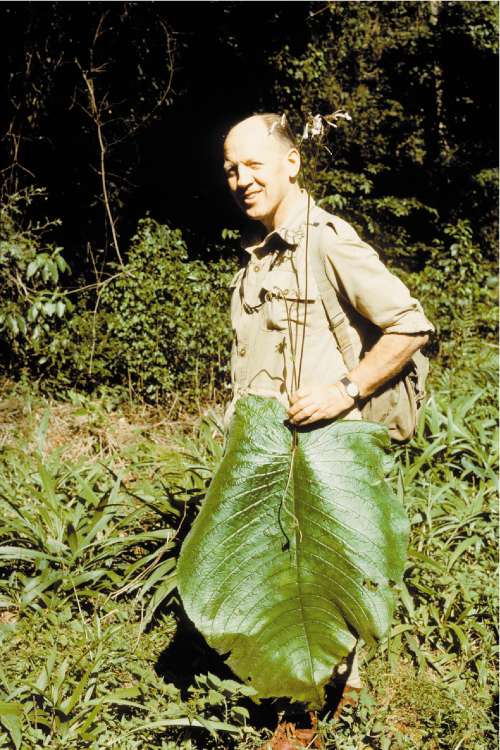

B. L. Burtt: Plant taxonomist

Prolific plant taxonomist at Kew and Edinburgh who described 637 species new to science

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.B.L. Burtt was one of the most prolific and knowledgeable of plant taxonomists, in the grand tradition of Sir Joseph Hooker. His long life was devoted almost exclusively to the classification of flowering plants and it is hard to imagine that his achievements can ever be repeated.

His first scientific paper was published from Kew in 1932, written jointly with John Hutchinson; his last from Edinburgh, with Olive Hilliard, in 2006 – between these came an astonishing 260 solo, 122 jointly authored papers and three co-authored books. Burtt's fieldwork included five trips to Sarawak, and 19 to South Africa, resulting in the collection of 19,102 dried herbarium specimens.

Alone, or in collaboration, Burtt described 637 species new to science, of which more than half were in the family Gesneriaceae (including Streptocarpus and African violets), the others spread across no fewer than 46 families, but especially Compositae (daisies), Zingiberaceae (gingers), Umbelliferae (hemlock) and Scrophulariaceae (figworts). Being of the old school, he would have hated these statistics – their citation he would have considered vainglorious, and the quoting of mere numbers pointless as compared with the work and meaning that lie behind them.

Brian Laurence Burtt (known as Bill) was born in Surrey in 1913 and obtained a classical education (with prizes in Latin and Greek) at Dulwich College, leaving at the age of 17. Through an army contact of his father, he entered the herbarium at Kew as assistant to the Director, Sir Arthur Hill. During this time he attended evening classes in botany at Chelsea Polytechnic and took an external London University BSc in 1936.

The experience of this period moulded the interests and methods that were to be relentlessly pursued for the rest of his career – a scientific education grafted onto a classical, and, at Kew, exposure to a heady world of horticulture and international botany under the tuition of an inspirational boss, surrounded by distinguished colleagues. Through Hill, Burtt learned the importance of evidence from the living plant and commonly overlooked features (such as the seedling stage), towards a broad systematic view – allowing the making of classifications that attempted to reflect evolutionary history more accurately than those based entirely on dried specimens.

This gave rise to a love of gardens and the opportunity of collaborating with the great horticulturist E.A. Bowles on crocuses and colchicums. But, at the same time, Kew, the botanical hub of the British Empire, was receiving herbarium specimens for naming from all over the world, and so Burtt had to develop the knowledge and skills to move, taxonomically speaking, from family to family and continent to continent.

Taxonomy is pre-eminently a historically based science, and it was also at this point, with Kew's great library at his disposal, that Burtt developed his passion and expertise for the works of the great botanists of the past. This work at Kew continued after wartime service with the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, working on the development of radar, including a spell in Nigeria and Cameroon.

In 1951 he moved to the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, then at a low ebb. Usually from behind the scenes, Burtt's intellect and vision played a critical role in transforming RBGE into one of the great botanic gardens of the world in terms of its scientific research, taxonomic teaching and horticulture.

He introduced a scientific research programme, including major work on Gesneriaceae and Zingiberaceae and brought new life to its long-standing work on Ericaceae. He transformed the Garden's scientific journal (Notes from the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh), and played a key role in designing the new library and herbarium. This state-of-the-art building was opened in 1964, the year the International Botanical Congress was held in Edinburgh. His teaching inspired students drawn from all over the world, and Burtt was hugely generous in sharing his vast store of botanical knowledge with any who sought his help.

It was during this period, in 1958, that Burtt made his first foreign botanical field trip (a Colombo Plan appointment to advise on the setting up of a national botanical infrastructure in Pakistan) and his first tropical trip to Sarawak in 1962, the latter of fundamental importance in studying and understanding his beloved "gesners" and gingers.

In 1942 Burtt had married Joyce Daughtry, but after their two sons had left school an amicable separation took place. A new phase in Burtt's life followed, in the form of an extraordinarily creative partnership with Professor Olive Hilliard, whom he met in South Africa in 1964 during research on the genus Streptocarpus. The Hilliard and Burtt collaboration, which was in equal measure inspirational and daunting to lesser mortals, lasted over 40 years, during which the word "retirement" (which technically came in 1975) had no meaning.

All of Burtt's old interests were retained and published upon, but an exciting new field opened up in their exploration of the remarkably unknown flora of the Drakensberg mountains of Natal and Lesotho. The expeditions on horseback, camping under the overhangs of cliffs, were a source of fascinating anecdote, but, more importantly, underpinned a frenzy of publication on particular plant groups. Some of these, including Dierama, Rhodohypoxis and Diascia, are of great horticultural merit, and members of all these genera can now be found in British gardens.

Apart from scientific papers, three major books resulted, Streptocarpus: an African plant study (1971), The Botany of the Southern Natal Drakensberg (1987), and Dierama (1991), on the elegant Iridaceous wandflower. These were designed to be useful both to scientists and gardeners, and are profusely illustrated – Dierama with outstanding paintings by Auriol Batten (Burtt's earliest papers having been illustrated by another renowned artist, Stella Ross-Craig, a lifelong friend).

Despite Burtt's unfashionable desire to avoid any hint of limelight, his achievements could not fail to receive recognition in the form of honours – fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1954), the Veitch Memorial Medal of the Royal Horticultural Society (1971) and the Linnean Medal for Botany from the Linnean Society of London (1981).

To outsiders Burtt appeared the archetypal reserved English gentleman. There was, however, another side to Bill, a love of music (Brahms, Beethoven, Schubert) and of poetry (Helen Waddell), revealed in print on a single occasion – a review of a translation of the "Hortulus", a poem by the ninth-century monk Walahfrid Strabo. A quote from this poem epitomises the humility and philosophy of Burtt's life's work:

Now I must summon all my skill, all

My learning, all my eloquence, to muster

The names and virtues of this noble harvest,

That this my lowly subject may receive

The highest honour that my heart can give.

H.J. Noltie

Brian Laurence Burtt, taxonomist: born Claygate, Surrey 27 August 1913; Senior Principal Scientific Officer, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh 1951-75; married 1942 Joyce Daughtry (died 2003; two sons), 2004 Olive Hilliard; died Loanhead, Midlothian 30 May 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments