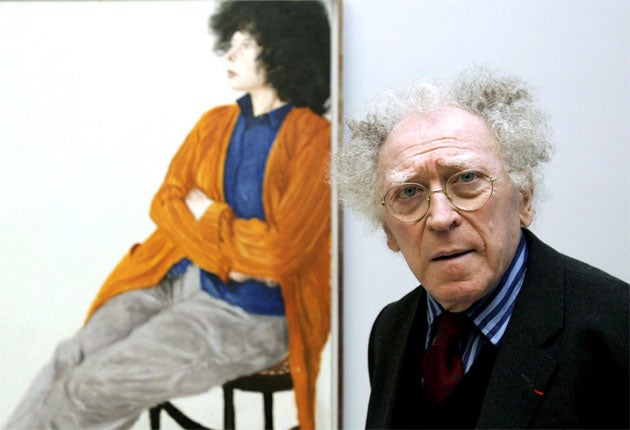

Avigdor Arikha: Artist and scholar who sought to capture existential truths in the everyday

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The apparent simplicity of the representational paintings, drawings and prints made by Avigdor Arikha over the last four decades of his life masked a rare sophistication and visual intelligence that bridged the modernist avant-garde of pure abstraction with traditions of observational drawing and painting stretching back to the Renaissance and beyond. He was truculently insistent that he was not part of any "return to figuration", but rather had found his own way as "a post-abstract representational artist".

Arikha's mature pictures were unapologetically beautiful and tender, depicting scenes of domestic life in and around his studio and apartment in Paris; this gave some the misleading impression that he was a mild traditionalist. Certainly his pictures are easy to like and generous towards the spectator. But there was no timid desire to please in Arikha's approach; his insistence on the everyday was born of a conviction that through an extreme attentiveness to the subtleties of experience one could convey a reverential celebration of the mystery of being alive. "Only this is true", he was fond of remarking when explaining why he worked only from direct observation, completing every picture in a single session.

The meditative humility of Arikha's picture-making was often rather vaguely labelled Realism, but he was not concerned with social history or with documenting the mere look of things; even "naturalism" falls short of describing it. Like Lucian Freud (a painter he much admired), but with a much lighter touch, he made pictures that strike the viewer as convincing equivalents to people he had encountered, to things he had witnessed and to specific experiences. Despite his great friendship with Henri Cartier-Bresson, it would not have crossed his mind ever to make reference to photography when the spectacle of the world itself was there for the taking. By the same token, he was infuriated by talk of "the image", rejecting the concept – however powerfully conveyed by contemporaries such as Andy Warhol – as an impoverished and modish substitute for picture-making.

Arikha was unapologetically sure of the path he had taken after first making his name as a painter of refined, sensuous and intellectually rigorous abstractions. He rejected, at least for his own work, the notion of painting from memory or the imagination, since he considered it essential to respond always to what was in front of his eyes. His profound admiration for Chinese brush painting – with its insistence on the continuous energy of the stroke through the entire picture – was evident in everything he did, but particularly in the virtuosic paintings on rag paper made with brushes and sumi ink.

The traumatic circumstances of Arikha's childhood as a Jew during the Second World War coloured not only his life, but more specifically his dedication to art. He was born in Radauti, then in Romania, in 1929, and shortly afterwards the family moved to Czernowitz. He was deported, with his family, to a Ukranian labour camp at the age of 12. There he made drawings bearing witness to the atrocities he had seen. In 1944 he and his sister were transported by the International Red Cross to Palestine. His father had already been beaten to death, and he was not to see his mother for the next 14 years.

Arikha studied art in Jerusalem before making his way to Paris in 1949, where he established himself as a painter of complex abstractions. But he underwent a conversion in 1965 after seeing an exhibition at the Louvre of Caravaggio and 17th-century Italian painting. For the next eight years, he drew solely from life, and discovered his métier as a portraitist, landscapist and still-life artist.

When in 1973 he began painting again in oils, working "alla prima" (wet into wet) on canvases completed all in one go, he had a very clear conception of his territory. Though he later made some beautiful landscapes in Israel, he had little need to venture out of his apartment and studio in order to find ample subject matter. With delicacy and deftness, he applied the sense of order he so admired in the paintings of Mondrian to motifs spied in his immediate environment.

For his portraits Arikha generally favoured family and friends, although he later also painted Catherine Deneuve and produced commissioned portraits of unusual informality and sensuality of the Queen Mother and Sir Alec Douglas-Hume. The tenderness suffusing his nudes is evident also in his many portraits of his wife, the American poet Anne Atik. Arikha's concern with the truth was perhaps most in evidence in his self-portraits; frank images of his sagging middle-aged body in the mid-1980s and, poignantly, a pastel self-portrait of 2007, After Surgery, showing him in a hospital gown with a bandaged head after the operation for skin cancer that was to prove the beginning of the end.

Arikha had a parallel and distinguished career as an art historian, writer, lecturer and curator. Foremost among the artists he wrote about were two French painters in the classical tradition, the 17th-century Nicolas Poussin and the 19th-century master draughtsman J A D Ingres. The breadth of his scholarly interests, comparable to his fluency in several languages including Hebrew, French and English, encompassed not only such 19th- and 20th-century French artists as Daumier, Degas, Bonnard and Matisse, but also Caravaggio and Memling. He wrote passionately about the importance of natural light when displaying paintings, arguing that artificial light catastrophically altered both tones and hues. A French 1994 collection of his writings was translated and published in English as On Depiction (1995).

Though he exhibited frequently with Marlborough's London and New York galleries from 1974 onwards and had various retrospectives, including at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem (1998), the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh (1999), and the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid (2008), Arikha felt marginalised in Paris, where he had settled as a young man in 1949. Nevertheless he was held in high esteem both as an artist and scholar in France, where his prints were the subject of a retrospective at the Bibliothèque Nationale in 2008 and where for many years he had a certain influence (unusual among practising artists) at the Louvre.

A major donation by the artist of more than 100 drawings and prints to the British Museum became the subject of an exhibition there in 2006, cementing his already close relationship with the UK. He divided his time between Israel and the French capital. His wife described him as "Israeli in heart and language and culture and citizenship, and also French (Parisian) in heart, language and culture." In Paris he was sustained by his close friendship with Samuel Beckett: their great mutual admiration, and their shared ability to wrestle a profound philosophical response to life with a complete lack of pretension was manifested in the many informal portrait drawings and etchings that Arikha made of the playwright.

Arikha could be difficult, unforgiving, uncompromising and argumentative, and even some of his closest friendships ended in silence and recriminations. He fell out for a while with the equally strong-willed American artist, R B Kitaj, though they were eventually reconciled. An evening in his company could feel like an oral exam for a doctoral thesis, with topics ranging from Michelangelo, to modern literature, to the frontiers of science and technology. Given his sometimes forbidding seriousness and the strictness of his opinions, which included a loathing of contemporary popular culture, his laughter always came as a welcome and joyous surprise. He was a human being of rare integrity, guided by his formidable intellect and his passions, and an artist of consummate grace who breathed life on to the surface of every canvas and every sheet of paper he touched.

Marco Livingstone

Avigdor Arikha, artist and scholar: born near Radauti, Romania (now Ukraine) 28 April 1929; married 1961 Anne Atik (two daughters); died Paris 29 April 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments