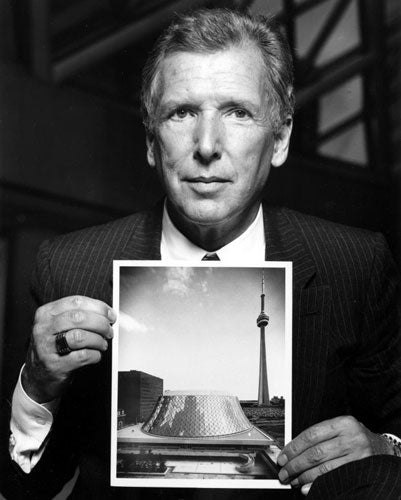

Arthur Erickson: Modernist architect celebrated as a master of concrete

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Canada's well-known modern architect Arthur Erickson died last month aged 84 in Vancouver. Last year, an exhibition was held at Canada House in Trafalgar Square acknowledging his unique contribution to architecture in Canada and other parts of the world. The exhibit included work by his former assistants James Cheng and Bing Thom, who described Erickson as one of "the greatest Canadians of all time. He has done so much to put Canadian architecture on the map." In a sense, he defined West Coast Modernism in Canada. He abhorred the post-Modernist phase in architecture, with its historicist and superficial ornamentation.

Outside Canada, the projects his largish firm carried out include the Napp Laboratories at Cambridge, the Kuwait Oil Sector Complex in Kuwait, the Kunlun Apartment Hotel building in Beijing and the San Diego Convention Center. He had branch offices in Los Angeles, Toronto, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Many of these schemes were big projects in their own right, but designed before the now current, iconic "star architecture" took over. His buildings were creative works of art, drawn by hand and both innovative and experimental. He was closely attentive to landscape details and usually built in concrete, a material he loved, calling it "the marble of our time".

Arthur Erickson was born in 1924, a native of Vancouver and the son of influential promoters of the arts. They encouraged him to establish contacts with other artists. However, it was the sight of an article in Fortune magazine on Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin West, Scottsdale that inspired him to take up the architecture course at Montreal's McGill University. He later commented in his autobiography that, "If such a magical realm was the province of an architect, I would become one." He did, graduating in 1950.

After graduation, his first major university project was for the Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, which he won together with his then-partner, Geoffrey Massey. Other work immediately followed, including his widely published and beautifully landscaped "horizontal skyscraper" for the Vancouver Law Courts, an elegant and transparent attempt to democratise the legal system. According to Erickson, with this building a passer-by was meant to be able to see justice at work.

Among other prestigious national projects was the Canadian Pavilion for Expo 67, shaped in the form of an inverted pyramid for that year's World's Fair in Montreal. He also designed the popular Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto. Less successful, perhaps, was the Canadian Embassy that he designed for Washington DC, which was a direct commission awarded by the Prime Minster of Canada, Pierre Trudeau, without due process.

At the Vancouverism exhibition at Canada House, it was claimed that Erickson was the first to believe that Vancouver "could be a world-class city". Subsequent events, including the concentration on a more diverse and dense urban planning fabric in the city, brought in more residential sites with expansive sea views, while commercial areas were moved to downtown sites such as Richmond.

The huge concrete superstructure that Erickson designed for the Museum of Anthropology (1976) at the University for British Columbia not only framed a splendid ocean view, but also provided generous spaces and superb light conditions for the tallest of all the Totems displayed within. A major achievement locally, it is undeniably one of the best buildings he designed, drawing as it does upon both local native cultural sources and the solid concrete technology of the modern movement.

A master of modern concrete, Erickson experimented with the rough-textured, concrete-framed commercial high building for MacMillan-Bloedel in downtown Vancouver in the mid-Sixties. Its neat, egg-crate façade is amplified by his use of an entasis that allows the building to reduce its structural loading towards the top, making it a more economical solution for high building.

Arthur Erickson, who was unmarried, is survived by his brother, Don Erickson, his nephews, Christopher and Geoffrey, and his niece, Emily McCullum.

Dennis Sharp

Arthur Erickson, architect and landscape architect: born Vancouver 14 June 1924; died Vancouver 20 May 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments