Arsène Tchakarian: Last of WWII’s Armenian-led Manouchian network who fought the Nazis in France

He joined a band of immigrants from countries affected by Hitler’s expansionism fighting for the French resistance

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Arsène Tchakarian was the last surviving member of the Armenian-led Manouchian network, which fought alongside the French resistance against the Nazi occupiers during the Second World War. An ethnic Armenian born in Turkey during the Ottoman Empire, he later received France’s highest award, as a commander of the Legion of Honour.

Tchakarian, who has died aged 101, was commemorated on Twitter by French president Emmanuel Macron, who described him as “a hero of the resistance and tireless witness whose voice resonated strongly to the very end”.

The Manouchian resistance network, named after Tchakarian’s fellow Armenian Missak Manouchian, a poet and resistance leader, was made up of immigrants from many nations that had been affected by Hitler’s expansionism – Italians, Greeks, Romanians, Hungarians, Bulgarians, Spaniards, Poles, even young German Jews who had fled to what was then a free France.

“There was such a friendship between us, between all these people coming from everywhere, Jews, Spanish, Italians, Germans, Armenians and French of course,” Tchakarian said in a 2002 speech to pupils at a junior high school near his home in Vitry-sur-Seine, France. “A brotherly friendship which surpassed all that you can imagine.”

Throughout the Second World War, the Manouchian network linked up with the local French Resistance to carry out a guerrilla campaign against the Nazi occupiers, including broad-daylight assassinations and the sabotage of power lines and munitions trains.

Tchakarian, code-named “Charles”, started out secretly distributing anti-Nazi tracts in Paris. After meeting Manouchian, he recalled that his fellow Armenian told him: “Enough of tracts, we are now being asked to fight with arms.”

Tchakarian’s first assignment was to throw a grenade among a group of Nazi soldiers.

“As I hesitated,” Tchakarian told Le Parisien newspaper in February, “Georges” – Manouchian’s nom de guerre – “snatched it from me and threw it himself.”

The following day, Tchakarian took part in an attack on German military police. He was also part of a small resistance cadre that assassinated SS General Julius Ritter in September 1943. Ritter had been in charge of a forced-labour programme that deported hundreds of thousands of French workers to Germany to support the Nazi war effort.

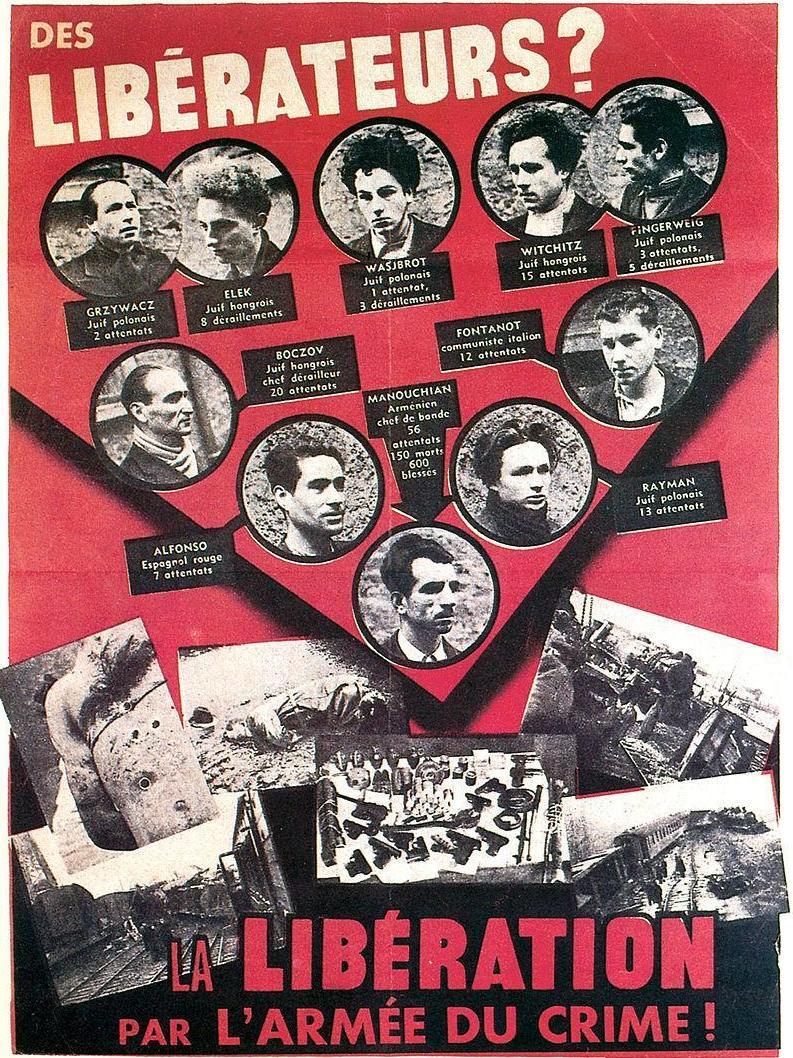

The Manouchian network later became better known as L’Affiche Rouge or the Red Poster Group, after the Nazi occupiers put up blood-red posters carrying the faces of the network’s wanted members, including Tchakarian.

The Germans called them “The Army of Crime” and focused on the fact that many of them were Jewish.

In November 1943, Tchakarian had scheduled a clandestine rendezvous with a fellow resistance fighter, Olga Bancic, a Romanian Jew, at the Gare d’Orsay in Paris.

“She didn’t show up, as she always had without fail,” Tchakarian recalled earlier this year. He had seen pro-Nazi police in the area and escaped shortly before Bancic was arrested along with Manouchian and 22 other male members of the underground network.

On 21 February 1944, all 23 men, including Manouchian, were lined up and shot by a German firing squad at the notorious Fort Mont-Valérien on the western outskirts of Paris. (More than 1,000 people, mostly Jews, were executed at the fort between 1941 and 1944.) Because French law prohibited the execution of women by firing squad, Bancic was taken to Germany, where she was beheaded with an axe.

Tchakarian fled from Paris to Bordeaux and continued the fight with the resistance. The German Luftwaffe had taken control of Bordeaux-Mérignac airport and was using it as a base for maritime reconnaissance and attacks against allied shipping in the Atlantic. Tchakarian helped provide intelligence for a 1943 raid on the airport by British and US bombers.

During the spring and summer of 1944, he joined a resistance group that, along with US army troops, helped liberate the central French town of Montargis. The soldiers and resistance fighters were greeted with kisses, flowers, wine and delirium by residents who knew by then that the war had turned against the Germans.

After the war, Tchakarian returned to his previous occupation and became a master tailor near Paris. He also turned his focus to history, writing memoirs about his wartime experiences and about the Turkish massacres of Armenians when he was a child. Most Armenians, including Tchakarian, described the killings as “genocide”, although Turkish authorities have continued to reject that term.

Arsène Tchakarian was born in 1916, to Armenian parents in what is now Sapanca, Turkey, then part of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Turkish purge of Armenians forced his family to flee first to Bulgaria and then to France.

Young Arsène, who adopted the French spelling of Arsène, arrived in Marseille in 1930 as an apprentice tailor. In 1937, though not yet a French citizen, he was conscripted into a French army artillery unit and fought the Nazis until they occupied France in June 1940 and he was demobilised.

He had come to consider France his home and was determined to fight on. Through Armenian connections, he soon found the Manouchians, the immigrant resistance group with nothing to lose.

Tchakarian was granted French citizenship in 1958. In 2005, he was made a knight of the French Legion of Honour, later upgraded to officer and finally to commander – France’s highest award – last year. His first wife, Bertha Christiane, predeceased him. Survivors include his second wife, Jacqueline Tchakarian, and four children. A complete list of survivors could not be confirmed.

In one of his last interviews, Tchakarian was asked about his time in the resistance.

“I would like to shed a tear,” he said. “But I cannot. I’ve never cried. We were not heroes. We resisted because we could do it: we didn’t have families or jobs. And we resisted because we loved France. She had adopted us.”

Arsène Tchakarian, Second World War French resistance fighter, born 21 December 1916, died 4 August 2018

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments