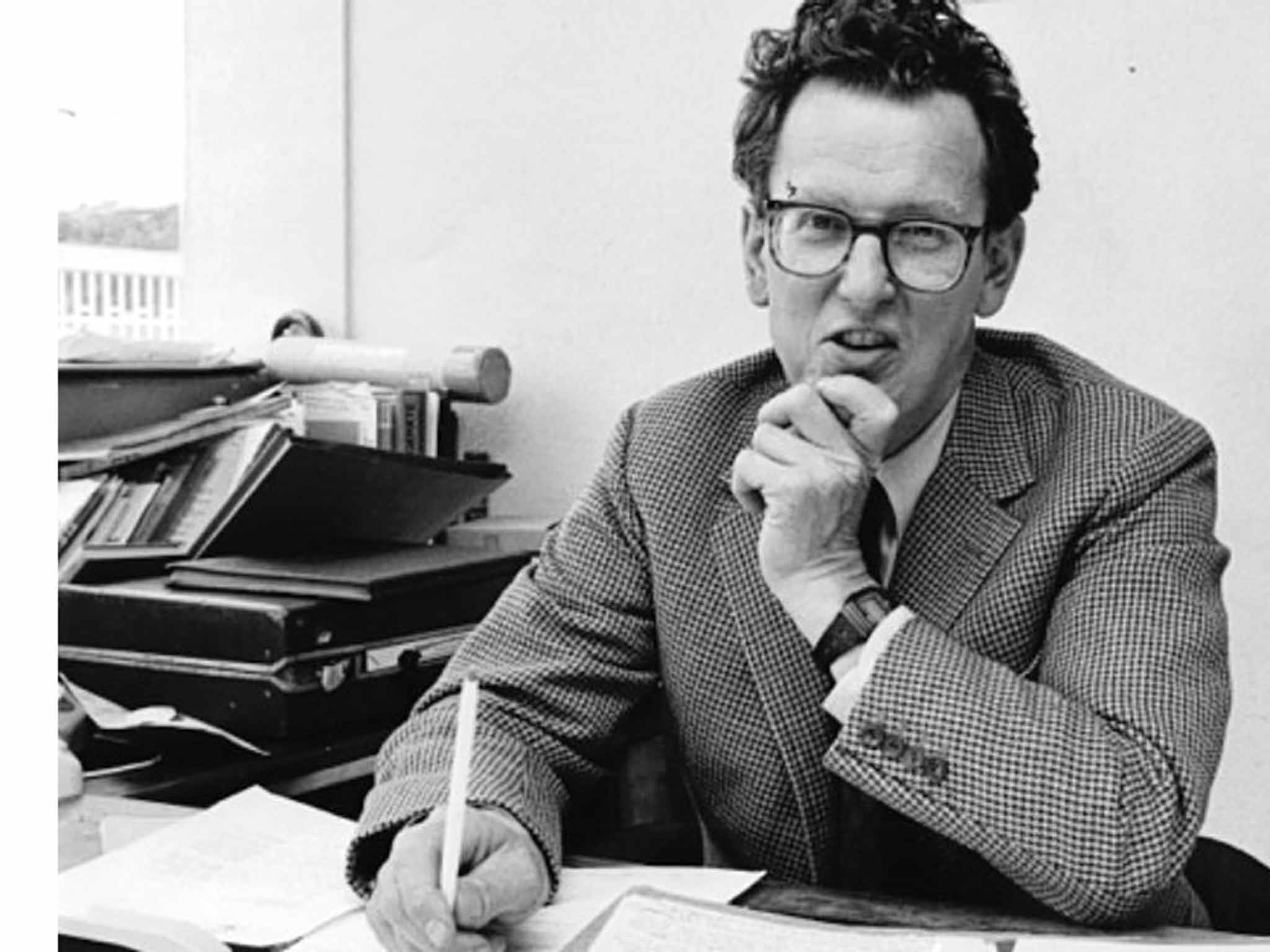

Andy Garnett: Leading figure of the 1950s London set who later helped develop one of Britain's most innovative engineering firms

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."Engineer, philanthropist and optimist" was the description of Andy Garnett given by Frances Lincoln, who published his book on conserving and documenting his meadow. Aside from the engineer ascription, it was a fair summary of an extraordinary character who was the only boy at Eton to convert to Roman Catholicism, who sped around London in a bubble car as a founding member of the London set in the 1950s and who went on to help Jeremy Fry, along with Michael Briggs, to develop the automatic-valve concern, Rotork, into one of the country's most successful small engineering innovation companies, and then did the same with his own company, Radiodetection.

In fact he was never an engineer, except by passion, and never attended university, being intended, quite unsuitably, for the army. When he joined his friend Fry in the recently formed Rotork in 1959 his reputation was more as a "flaneur", a man about town who was a joy to know but hardly cut out for serious business. He titled his autobiography Memoirs of a Lucky Dog, an archaism he relished in the same way he spoke of his friends always as "chums" and the girls of his youth as "dropsies". People he liked were "good eggs".

The only child of a forceful mother, and a father who separated from his wife when Andy was young, the boy had to work hard to be liked. Suffering from eczema, which resulted in repeated stays in hospital and a succession of ever more eccentric "cures", he was sent to Eton and shuffled around aunts and friends of his mother during his holidays. With a crippling self-consciousness about his skin he emerged from school to follow his mother's wish to go to Sandhurst, only to be turned down on medical grounds. He signed up as an ordinary conscript alongside the reluctant National Service recruits before his medical record caught up with him and he was discharged.

His life after that was one of drift and revelry; he joined a brewery in South Wales, Whitbreads in London as a ledger clerk, British Tabulating as a trainee and then the management consultant MWM, none of which stretched his abilities but which provided him with endless anecdotes with which to regale his friends. Living the bachelor life in Chelsea, Soho and the East End, gathering a band of friends for life such as Tony Armstrong Jones and George Melly, he was finally, aged 28, offered a job by his friend, Jeremy Fry, in his young automatic valve company.

Garnett proved his worth, first setting up the business in France, where he displayed an unexpected combination of determination and persistence, mastering the technicalities of his product and carefully preparing his plan of attack on markets and potential allies. He became sales director but the US proved a harder nut to crack – as it is still. Local companies were well entrenched and this idiosyncratic Englishman was an uncertain quantity, but through hard work he broke through in an industry they thought their own.

It was while at Rotork that Garnett met and wooed his wife, the writer and journalist Polly Devlin, then at Vogue. The story goes that he arrived at a dinner party with a French girlfriend. Seeing Polly, a fellow guest, his heart went "Wham Bam Boom Wow", as he put it. The French girl announced that she was asking Andy to marry her. Andy sidestepped an answer and, asked by Polly whether he was going to accept the French girl's proposal, he replied "No, I'm going to marry you."

Their wedding was in Italy – the bride given away by her brother-in-law Seamus Heaney – on 5 August 1967. The couple made two highly personalised homes, an Elizabethan manor house, Bradley Court in Gloucestershire and a farmhouse, Canwood, in South Somerset. Concerned at what he saw was growing energy shortages, Garnett rearranged Canwood around a central heat sink, doing away with internal corridors. Together with Polly he bought and nurtured a rare surviving meadow. He proposed a sprung floor in the main room of the barn so that it could be used as a ballroom for his three daughters, Rose, Daisy and Bay, oblivious of the fact that their generation no longer went in for that kind of occasion.

Tiring of the travel and with heart problems, he resigned as sales director of Rotork in 1978, taking with him a small company specialising in scanning equipment to detect underground pipes and cables. Although Electrolocation, as it was then called, had promising technology , it was in financially poor shape until Garnett, with the help of colleagues who had accompanied him from Rotork, took charge. Reorganising the management and introducing a new basic product, a handheld scanner that could be used by workmen in the field, he built up a thriving technological company until, sensing that it had grown beyond his competence, he sold it on to a venture capital group in 1993.

The great enthusiasm of his later years, and ultimately his great frustration, was his philanthropic venture into education. "Multi A", as he called it, was an effort to give confidence and self-discipline to schoolchildren in the deprived areas of Bristol through music, dance and the arts. At its height it was giving weekly classes to 3,000 children but, with it haemorrhaging money, he was forced to seek funds from the City and the Arts Council. Strangled by bureaucracy and unadventurous appointees, the venture eventually folded.

Garnett's last years were dominated by debilitating illness, Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy (CIDP). Stubborn and determinedly cheerful, he survived to see daughters married and grandchildren born. He died buoyed by the faith he held close throughout his life. At his funeral his family spoke the prayers he read every day, adapted to his personal conscience and broader concerns.

At the reception, one of his 28 godchildren recalled being rung up on his seventh birthday to be sung "Happy Birthday" in a gravelly voice. "That," came Andy's voice at the end, "was Louis Armstrong." Andy had met the great jazz musician in New Orleans and persuaded him to sing his birthday wishes to the boy.

Adrian John Fortescue Garnett, businessman: born 26 September 1930; married Polly Devlin (three daughters); died 10 July 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments