Andrei Mironov: Russian human-rights campaigner and translator who was a political prisoner during the Soviet era

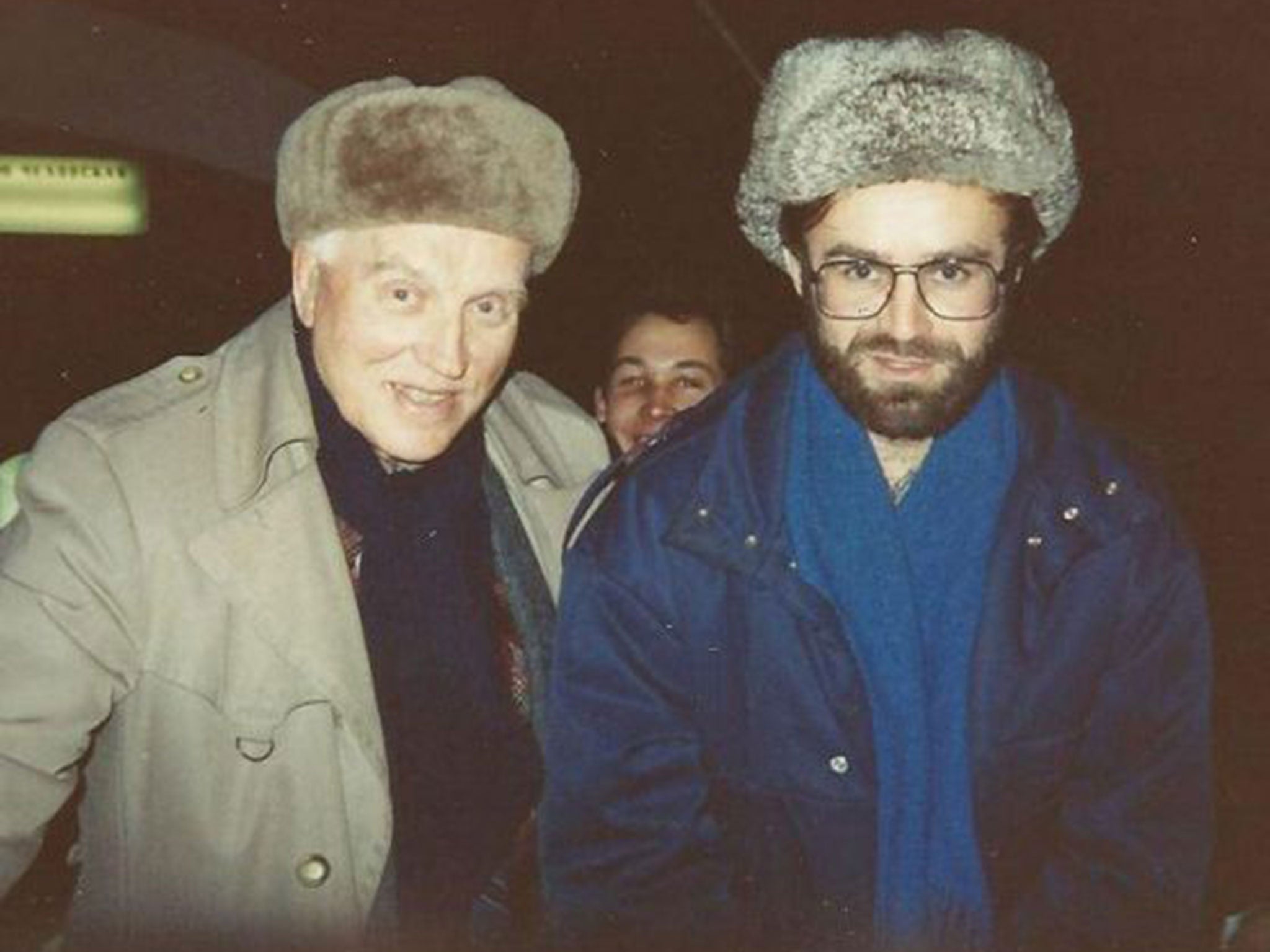

Andrei Mironov, who was killed in eastern Ukraine on 24 May, was a 60-year-old veteran of the Russian human-rights movement. He was apparently hit by shrapnel from mortar shells during a battle between Ukrainian forces and pro-Russian separatists near the village of Andreyevka near the city of Slaviansk. He had been acting as a translator for the Italian photojournalist Andrea Rocchelli, who was also killed in the incident.

Mironov was born in the Siberian city of Irkutsk in 1954, the family later settling in Izhevsk (renamed Ustinov in the years 1985-87), the capital of Russia's Udmurtia republic. His interest in human rights owed something to his family. Geophysicists by profession, his parents were privately very critical of the Soviet regime, their outlook reflecting the relatively independent attitudes of the Soviet scientific intelligentsia.

In 1974, following two years in the army doing military service, Mironov enrolled as a student at the Mendeleev Institute of Chemical Technology in Moscow, but he found that his mind was as much taken up with history and politics as chemistry, and he left within a year. During the next decade he became closely involved in the illegal copying and distribution of samizdat, and this resulted in his arrest in 1985. The arrest came as no surprise, as for some time Mironov had been tailed around Moscow by small groups of KGB men. The lengthy investigation that followed, which included 35 days in the kartser (isolation cell), was a harrowing experience.

One episode in particular he never forgot. An interrogator performed a near-strangulation upon him with a towel, and he lost consciousness. Yet he strangely found that he felt no hostility towards the interrogator, and indeed felt a peace within himself in the consciousness that he had been acting in the right way. He drew the conclusion that he was spiritually stronger than the interrogator. It reflected a wider message the dissidents often promoted: that it was possible to acquire a certain inner freedom even when living in an oppressive society.

Another memorable moment for Mironov came during his trial in 1986 when he was asked whether or not he was guilty. He replied "No," and then felt an overwhelming sense of relief that he had spoken truthfully – which, he suggested later, testified to the serious, and to a degree subconscious, interior struggle he had been undergoing.

Mironov was sentenced under article 70 by the Supreme Court of Udmurtia to four years in a labour camp and three in internal exile. He was sent to a camp for political prisoners in the Dubrovlag chain of camps in Mordovia. However, in February 1987 he was released, along with a number of other political prisoners, following pressure from the West.

Mironov's knowledge of languages – he learned Italian in the camp in Mordovia – meant that in the late 1980s he became involved in interpreting for and advising Western journalists and other visitors to Russia. He rarely succumbed to the lure of ordinary employment, believing that he needed to be available to respond quickly to situations as they arose.

He liked playing the role of helper and link-person, and was content with being out of the limelight – although his story was among those featured in Scott Shane's Dismantling Utopia: How Information Ended the Soviet Union (1994). An admirer of the physicist and dissident Andrei Sakharov, he was well-connected at the Memorial Society, founded in 1988 to record and bear witness to the history of Soviet repression.

Mironov's work to expose human-rights abuses often took him to areas of conflict. He visited the Russian republic of Chechnya many times following the war that broke out there in 1994, and he also spent time in Afghanistan in 2001 at the time of the collapse of the Taliban. The authorities remained wary of him. Mironov believed that an attack on him in a Moscow street in 2004 that led to him having medical treatment in Germany had been sanctioned by someone in government.

In 2008, he and Andrei Makarov (also connected to the Memorial Society) were awarded the Pierre Simon prize for ethics and society that is awarded every year under the auspices of the French Ministry of Health. In recent years Mironov was a regular presence at anti-government demonstrations, and was apprehended by the police on a number of occasions. He was positively impressed by the Maidan demonstrations in Kiev.

Although strongly committed to the Russian human-rights movement, Mironov was not uncritical of it. He was unhappy about internal divisions and personality differences within it. He always insisted that Russia needed to develop a greater capacity for dialogue if it was to succeed in developing a strong civil society. In this context he was an admirer of the peace campaigner and former member of the Norwegian wartime resistance, Leif Hovelsen. Hovelsen, who had been tortured by the Gestapo, had a message of forgiveness and reconciliation that appealed to Mironov, and he regularly translated for Hovelsen during the latter's frequent visits to Moscow in the post-Soviet era.

Mironov is survived by his mother and two brothers. He lived with one of them, Aleksandr, in a small flat near Moscow's Mayakovsky Square. As well as being a man of conviction, he had a good sense of humour. After his death, the social activist Svetlana Gannushkina described him as a person with a "crystal clear soul, absolute unselfishness, a limitless, uncompromising sense of justice, a remarkable kindness and belief in goodness". It is a good summary of how his many friends in Russia and the West – including myself – will remember him.

PHILIP BOOBBYER

Andrei Nikolaevich Mironov, human-rights activist: born Irkutsk, Siberia 31 March 1954; died Eastern Ukraine 24 May 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments