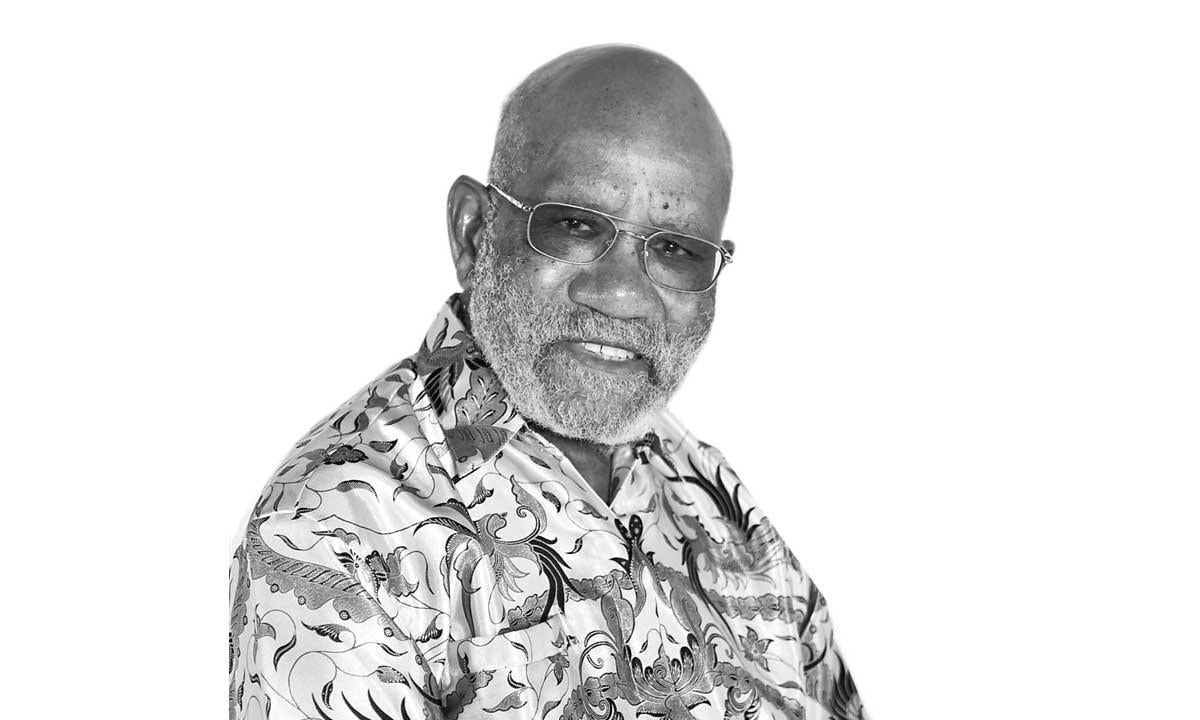

Andimba Toivo ya Toivo, obituary: Namibian independence leader admired by Nelson Mandela

As an activist since the 1950s, he had helped to found his country’s independence movement and spent 16 years imprisoned on Robben Island

Andimba Toivo ya Toivo was a Namibian independence leader whose struggle against his country’s South African rulers landed him for 16 years in the notorious prison on Robben Island, where his steadfastness earned him the admiration of Nelson Mandela.

Ya Toivo fought what was described as a decades-long war of nerves with South Africa on behalf of Namibia. South Africa assumed control of the former German colony, then known as South West Africa, through a League of Nations mandate at the end of the First World War.

To Ya Toivo and his supporters, South African rule became particularly intolerable – although it had always been unacceptable – after the country instituted the apartheid system in 1948. An activist since the early 1950s, he had helped found the independence movement, the South West Africa People's Organisation, or Swapo, which challenged South African rule through protest and guerrilla warfare.

In 1968, after being convicted of violating a terrorism law, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison, where he was tortured and put in solitary confinement. He had faced possible execution but credited a lawyer, who reportedly engaged the help of American officials including senators Robert and Edward Kennedy, with helping him avoid it.

During his trial in Pretoria he drew international attention to the Namibian cause, declaring: “We find ourselves here in a foreign country, convicted under laws made by people whom we have always considered as foreigners. We find ourselves tried by a judge who is not our countryman and who has not shared our background. We are Namibians and not South Africans.”

Entering prison, he said he knew “the struggle will be long and bitter [but] I also know that my people will wage that struggle, whatever the cost”.

Mandela arrived on Robben Island in 1964 and came to regard Ya Toivo as “a formidable freedom fighter.” Ya Toivo refused to participate in the behaviour grading system instituted by wardens that might have allowed him improved conditions – but that would have conceded the legitimacy of South African authority.

“He didn’t care to be promoted and he wouldn’t cooperate with the authorities at all in almost everything,” Mandela recalled. “He was quite militant. He wanted very little to do with whites, with the warders.”

At one point, Mandela took part in a hunger strike to show solidarity with the Namibian prisoners. On another, after a guard reportedly attacked him, Ya Toivo returned the assault, ending up in solitary confinement. He said he received three or four visits in all his years of imprisonment.

His captors noticed his resolve. “Ya Toivo would not bend when others took bribes in prison in order to get more privileges,” Christo Brand, a former guard, told The Namibian in 2014 on ya Toivo’s 90th birthday. He was, said Brand, “cut out of the same rock as Mandela.”

Ya Toivo was released in 1984 and went into exile. Namibian independence did not come until 1990, in part because of its small role in the Cold War. Namibian insurgents received support from the Soviet Union and Cuba. In exchange for the peace agreement that permitted independence, Cuban troops were eventually forced to withdraw from another Communist-backed African nation, Angola.

After independence, Swapo became Namibia’s ruling party, with Ya Toivo serving as secretary general. He also served as minister of mines and energy, labour and prisons under President Sam Nujoma, a former Swapo organiser who had spent years in exile.

According to most accounts, Ya Toivo was born Herman Andimba Toivo ya Toivo in the village of Omangudu, in northern Namibia, in 1924. Another report said he was born Andimba Mwandecki and was given the name Toivo ya Toivo, “hope of hope”, at the Finnish mission school he attended.

He serving with the Allies in the Second World War, then worked as a teacher before moving to Cape Town in 1951. He became a leader in the left-wing Modern Youth Society and helped form precursors to Swapo.

Shortly after he was released from prison, he attended a rally held by the radical feminist leader Angela Davis in New York, and met Vicki Erenstein, an American lawyer. They married in 1990, and had twin daughters and three adopted children.

“I have come to know that our people cannot expect progress as a gift from anyone, be it the United Nations or South Africa,” Ya Toivo said, speaking before the court that would send him to prison in 1968. “Progress is something we shall have to struggle and work for. And I believe that the only way in which we shall be able and fit to secure that progress is to learn from our own experience and mistakes.”

Andimba Toivo ya Toivo, freedom fighter and politician, born 22 August 1924, died 9 June 2017

© Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies