A Life in Focus: Amos Oz, Israeli literary colossus and lifelong advocate of a two-state solution

The Independent revisits the life of Amos Oz, who has died aged 79, with an interview from Thursday 19 March 2009

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The unlikely story of the state of Israel – 60, sullied, surviving – is intertwined with the unlikely story of Amos Oz. He is, all at once, its most distinguished novelist, its most passionate defender, and its most notorious “traitor” – a word he uses about himself. His friend David Grossman says, “Amos is the offspring of all the contradictory urges and pains within the Israeli psyche.”

To spend a day in his company – to follow his story from the birth of the state to the suicide of his mother, from Zionist idealism to a broken heart – is to tour the dizzying dissonances of the Jewish state as it staggers into the 21st century.

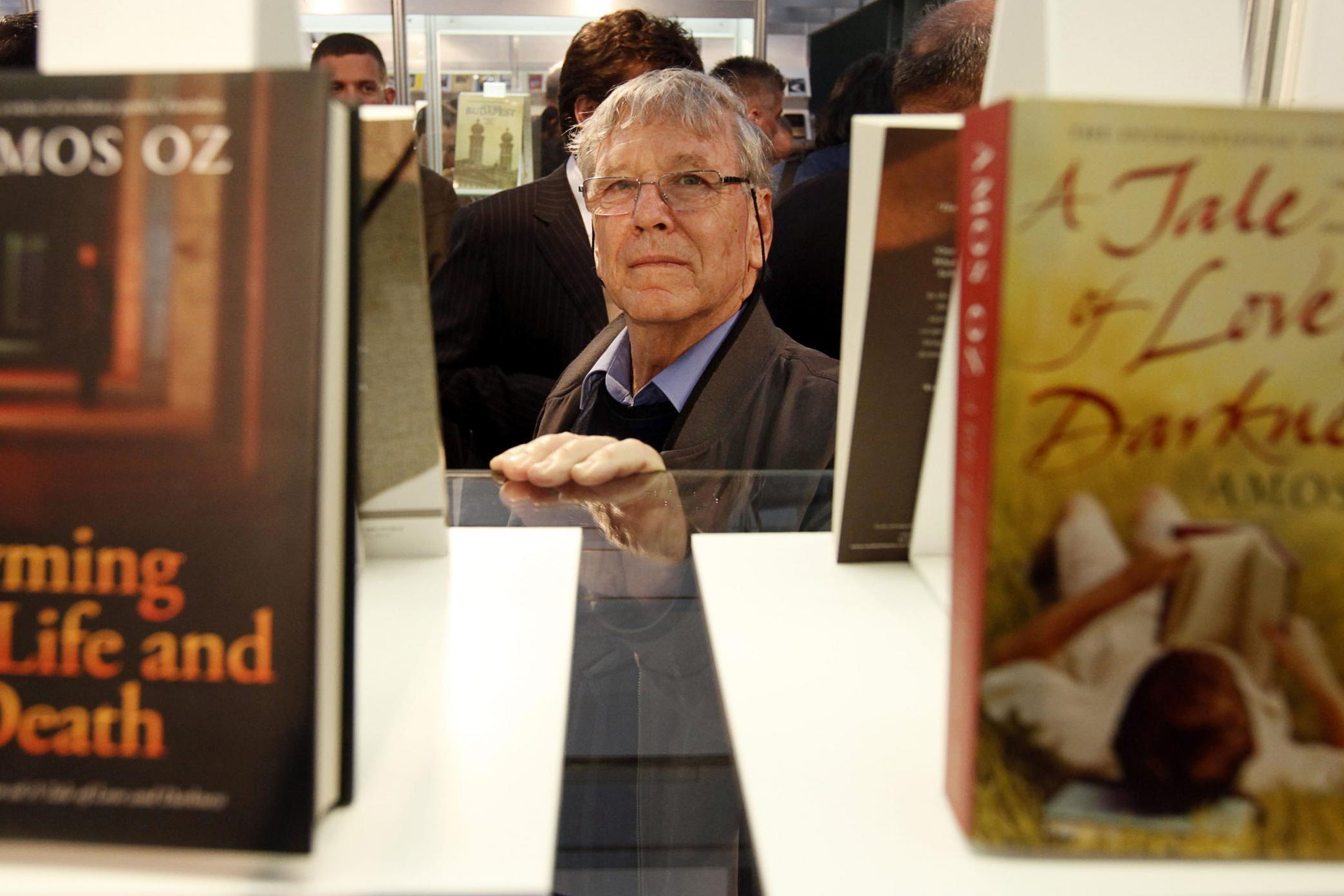

Oz is sitting in the coffee shop of Joseph’s bookstore in Golder’s Green, north London, looking older and more fragile than his vigorous black-and-white author’s picture. He is 70 now, his hair wispier and whiter. He greets me with a gravelly voice, and we order black coffees. It seems far away and long ago, but Oz once dreamed of bombing this city. He was once a child of what he calls “the Jewish intifada” – the stone-throwing, death-defying Jewish rebellion against British occupation.

He believed the state that would emerge from the rubble would be a model of justice and idealism for all mankind. If you were a child in Gaza now, Mr Oz, would you be dreaming the same dreams against Israel? “I don’t even have to imagine the answer to this question – I know it,” he says. “Because I was a kid in Jerusalem in ‘48 when the city was besieged, shelled, starved, [and] the water supply [was] cut off.

And I know the horror, and I know the despair, and I know the hopelessness, and I know the anger, and I know the frustration.” He says he was “not so much a child as a bundle of self-righteous arguments, a brainwashed little fanatic, a stone-throwing chauvinist. The first words I ever learnt to say in English were ‘British, go home!’”

In his novel Panther in the Basement, he writes: “This is how I remember Jerusalem in that last summer of British rule. A stone city sprawling over hilly slopes. Not so much a city as isolated neighbourhoods separated by fields of thistles and rocks. British armoured cars stood at street corners with their slits almost closed, their machine guns sticking out in front like pointing fingers: You there!”

At the age of eight, he built “an awesome rocket” in the backyard of his house. His plan was “to aim it at Buckingham Palace. I typed out on my father’s typewriter a letter of ultimatum addressed to His Majesty King George VI of England... Torrents of blood, soil, fire and iron intoxicated me.” His favourite song – a Stern Gang anthem – proclaimed: “We must fight until we breathe our last breath!”

So how did this boy, from this place, end up co-founding Peace Now, and fighting for a free Palestinian state alongside Israel? What contortions did he travel along the way, and since? And how did Israel’s story come to this?

I. Jerusalem Dreams

Amos Oz was born in Jerusalem because his parents had nowhere else to go. They were running for their lives. “It was the only life raft they could find,” he says. “My parents, they tried to become American, they tried to become British, they tried to become Scandinavian – nobody wanted them, anywhere. So, it’s a very common error to assume that in the 1930s, my parents went to a travel agency and inquired about a holiday resort, and they made a mistake – they should have said, ‘the French Riviera,’ and by mistake they said, ‘Jerusalem.’”

It was a city of “dusty tin roofs, urban wasteland of scrap iron and thistles, [and] parched hillsides”. For his parents, it was a barren shock. They were “troubled refugees from Europe, who loved Europe and were kicked out by Europe, who were devoted Europeans at a time when no-one else was a European. Everyone [else] was a pan-Germanic, or pan-Slavonic, or just a Bulgarian or a British patriot. The Jews were the only European Europeans at that time – and Europe kicked them out. They were labelled cosmopolitans, they were labelled ruthless intellectuals, they were labelled parasites. And they came to Jerusalem hoping to create a tiny little Europe in the heart of the Middle East – a European enclave. Which they couldn’t, of course. Because there was no Europe. Because their idea of Europe was no more than an idea, not a reality. The Europe of their love, the Europe they loved, did not exist, except in their own imagination.”

Oz’s mother, Fania, was born to a wealthy Jewish family in Rovno, a city in western Ukraine. She dreamed of being an artist, and soaked herself in the works of Anton Chekhov. But by the time she went to university in Prague, the tide of antisemitism was rising fast. She got out just in time: the Nazis killed her brother, her sister-in-law and her nephew. They killed almost all her school friends. They killed the world she grew up in – and then Stalin swept away anything that remained.

So Fania was left beached in Jerusalem, a dry, dusty city that seemed wholly alien to her. Oz says her life consisted of “the introspective, melancholy menu of loneliness in a minor key... If you ever spoke about the past, something bitter and desperate would creep into her voice.”

His father, Arieh, was forced to leave Lithuania. He was “a cultivated, well-mannered librarian, severe but also rather shy,” Oz says, who believed his true destiny – to be a great scholar of Hebrew literature – was inexplicably thwarted. When he arrived in Jerusalem, he aligned with the Israeli right, who believed the Arabs in Palestine had to be ruthlessly fought and forced out. Fleeing the Nazi persecution of the Jews, he believed Jews had to show strength to the point of brutality, or die. He wrote propaganda for the Stern Gang, which bombed British targets and Arab civilians, and were labelled as terrorists.

Still, his parents felt a sense of inferiority, and exclusion, even within Israel. “We were out-of-the-way Israelis,” he says. “The drama took place in Galilee, in the valleys, not in Jerusalem. Jerusalem was out of the way. And my parents were cut off [from] the mainstream of the enthusiasm of the Zionist revolution. They were cut off because they were right-wingers at a time when everyone was a socialist, they were city dwellers when everybody was a toiler of the land, they were academics at a time when academics were regarded with a certain suspicion.”

On the night the United Nations voted to establish the State of Israel on part of British Mandate Palestine, Arieh crawled into bed with his eight-year-old son. He whispered: “From now on, from the moment we have our own state, you will never be bullied just because you are a Jew. Not that. Never again. From tonight that’s finished. For ever.” It was the only time Oz ever saw his father cry.

That is how he ended up – like a child in Gaza today – under siege. He remembers “the war, the shelling, the siege and starvation” in fragments. He lived in what felt like a “dank submarine”, crammed into his house with his parents and a host of other families. He slept on a mattress in the corner with his parents while the food was rationed, the windows were sandbagged, the medical supplies ran down to nothing, and the toilets overflowed with faeces because there was no water to flush them. “Every few minutes, when a shell landed, the whole hill shook, and the stone-built houses shuddered,” he says. There was “a massive bombardment whose aim was to cause losses among the civilian population, break their spirit and bring them to submission”.

His parents were great linguists: his father spoke 11 languages, and read 17. Yet even when they were locked up together like this with nothing to do, he says: “The only language they taught me was Hebrew. Maybe they feared that a knowledge of languages would expose me, too, to the blandishments of Europe, that wonderful, murderous continent.”

He was raised under bombardment to be a militant, scorning the British, the Arabs, and the entire Jew-hating world. His grandfather taught him: “We have to beat them up so they’ll come and beg us for peace.” Does he feel angry when he thinks about the child he was? “No – I feel amused. Bitterly amused. I was a product of a militant upbringing in a militant time, in a state of war, and I grew up in a world where everything was black and white. We were white and our enemies were black. And our enemies were not just the Arabs but the rest of the world. The entire world. The Germans, Europe, Russia – everybody was our enemy. We were alone in the world – we were the few and the just. There was something very sweet about such a simple world, which divides into goodies and baddies, something very attractive for a child in particular, of course, and everything fell neatly into place.”

There seems to have been an extraordinary pressure on this only child – to be everything his parents had failed to be. When his father finally had a slim work of scholarship published, he inscribed it to his 11-year-old son: “To my son Amos, in the hope he might carve out a place in our literature.”

Both his parents were “immensely inhibited”, and could express little emotion beyond this burning ambition. As the news of her family and friends’ deaths began to filter through to Israel, Oz’s mother became ill and withdrawn. She began to experience “headaches” that lasted for months, and required her to inhale mysterious medicines all the time.

And then, one night, once the state was born and Amos was 12-and-a-half, she walked through a Jerusalem rainstorm to her sister’s flat, went to bed, and took a massive overdose. Having run for her life, she now ran to her death. Was there an element of survivor’s guilt in her suicide? He looks away. “Possibly. I don’t know. I don’t know the reasons why she killed herself and I no longer make an attempt to know. I doubt it that... in most cases, when a person kills himself or herself, I doubt it that there is such a thing as one reason. There is an excuse, there is an immediate motive, but there is more than just one reason.” He knows his father had an affair; he knows his mother felt lost in Jerusalem.

“I was very angry with her,” he says. “I was very angry with my father, I was very angry with myself. I blamed every one of us for the calamity,” he says. He wasn’t allowed to go to the funeral. The rage lasted for decades. “There was not a drop of compassion in me. Nor did I miss her. I did not grieve at my mother’s death. I was too hurt and angry for any other emotion to remain.” It was only, he explains, “when I reached the age when I could be my parents’ parents [that] I could look at them with a combination of compassion, humour and curiosity.” He made them the subject of his masterpiece, his memoir A Tale of Love And Darkness.

He never once discussed his mother’s death with his father: “We continued as if she had never lived.” But now, through writing, he could express everything he wanted to say. “It was about inviting the dead to my home, offering them a cup of coffee, and saying – let’s sit and talk about that which we never discussed when you were still alive. This is a highly recommended practice: invite the dead to your home from time to time, offer them a coffee and a cake, engage yourself in a good conversation with the dead, and then tell them to go away – don’t let them stay in my house. Drop by from time to time. That’s the proper relationship between the living and the dead.” Was it having children himself that made him finally able to forgive his mother? “Yes, definitely,” he says with a firm nod. In what way? He is silent for a long time. “This is too personal. I will not discuss that, if you’ll forgive me.” Then he adds, to change the subject: “I just became old enough to imagine them as immature people. I lost interest in the question of whose fault it is.”

Two years after his mother committed suicide, Amos Oz left his father and his father’s world – and began his metamorphosis into a very different person.

II. Courage

At the age of 14, Oz has written: “I killed my father and the whole of Jerusalem, changed my name, and went on my own to Kibbutz Hulda to live there over the ruins.”

He ran away from Jerusalem to a kibbutz – and abandoned his father’s surname, Klausner, for one of his own invention.

“‘Oz’ means strength – and it also means courage,” he says now. “When I left home at 14 and a half, I decided to become everything [my father] was not, and not to be anything that he was. He was a right-wing intellectual; I decided to be a left-wing socialist. He was a city dweller; I decided to become a tractor driver. He was short; I decided to become very tall. It didn’t work out, but I tried – I tried. So, I assumed the name ‘Oz’, because this courage and strength are what I needed most.”

Back in Jerusalem, nobody had asked what happened to the Arabs who had lived in Palestine. They vanished during the war; that was all. In the kibbutz, Oz began to hear whispers – initially to his shock and indignation. This had been their land, and they had been driven from it, by force, by us. Could it be true?

Slowly, he began to imagine the Palestinians driven from their homes, scattered in rotting refugee camps somewhere beyond Israel’s borders – and to see their similarity to his own parents. He reached the conclusion “that the clash between Israeli Jew and a Palestinian Arab is a tragedy, not a wild west movie, with good guys and bad guys. It’s a tragedy, because it is a clash between right and right. The Israelis are in Israel because they have nowhere else to go. The Palestinians are in Palestine because they have nowhere else to go. This is a conflict between victims, and between people who both have a just claim to the land.”

In 1967, this became a crucial insight, changing the course of Oz’s life. He was conscripted and fought on the Egyptian front in the Sinai desert. “I have almost never written about my experience as a soldier on the battlefield, because I tried, and I found that it is beyond my capacity to describe the battlefield,” he says. “The battlefield consists mostly of smells, and it is very difficult to describe smells in words – very difficult indeed. There is a stench on the battlefield which doesn’t come across in war movies, and in television documentaries, and it doesn’t even come across in the reportage of death and devastation and destruction on the battlefields. And this particular stench, which I remember very vividly, very physically, I remember the stench – this I simply cannot describe in words, and without the stench the description will be false.”

How did he sustain himself? “When you’re on the battlefield, you switch off your soul, otherwise you would die of terror – you would die of fear. You switch off your soul and you act like an animal or a machine. People under fire change greatly. You know what my first response was? When I found myself under fire, and I could literally see the Egyptian soldiers – it was in ‘67 – these Egyptian soldiers on the next hill, firing mortar shells at us, and the mortar shells exploding in armies. My immediate instinct was, ‘Call the police. These people are insane. They can see that there are people here and they are shooting at us.’ Maybe that was the last sane response on the battlefield: ‘Call the police’.”

He says, however, he did not do anything he regretted. “I don’t think so, no. I have done many things that I am sorry I had to do, but nothing that I am ashamed of. For me, fighting, both in 1967 and in 1973, was a last resort, because I knew very boldly that if I don’t fight, and if the others don’t fight... my family will be killed – we will be thrown into the ocean. It was not about territories, it was not about holy places. It was about life and death. And such a war... even though that I am an old man now, I would still fight such a war. If they put me with my back against the wall, and they would say, ‘Either you fight or your family gets killed,’ I’ll fight.” The wars to defend the settlers – or the invasion of Lebanon in the 1980s – are different, he says: “I would rather have gone to prison than fight for them. I would have refused to fight for occupied territories. For an extra bedroom to the nation. For holy places. For resources. I would refuse to fight for anything except for life and freedom.”

Amid the triumphalism and the first flood of settlers, Oz was one of the first Israelis to say the land other soldiers had conquered – Gaza and the West Bank – should be returned to the Palestinians for a state of their own. “I asked myself, ‘How would I feel if I were a Palestinian in the West Bank and in Gaza?’ And, unlike most Israelis – who assumed naively that the Palestinians will be happy about the Israeli occupation, because Israel will bring with it a higher standard of living, and perhaps a better legal system – I immediately could imagine the anger, the frustration, the hatred, the despair of the Palestinians. So I started advocating a two-state solution. And at that time, there were very few of us. In fact, we could conduct our national assembly inside a telephone box.”

He was immediately dubbed a “traitor”. He says with a smile: “I take this as a compliment. A traitor is he who changes in the eyes of those who cannot change and do not change and does not even conceive a change.” All the great Jewish heroes were traitors in their time, he notes: “Jonathan and Michal betrayed their father Saul; Joab and the other sons of Zeruiah, the fair Absalom, Ammon, Adonijah, son of Hagith – they were all traitors, and the worst traitor of all was King David himself, David about whom we still sing the song, ‘David King of Israel lives, lives, lives on still.’”

And Oz was indeed betraying his father’s vision. He told his son he was “crazy. Simple as that,” Oz says. “We had some fierce arguments about peace and about the Palestinians. My father never recognised the Palestinians as a separate national entity. He thought there is a pan-Arabic nation, and this pan-Arabic nation has a territory which is 150 times bigger than the territory of Israel. ‘They have enough space. What do they want of us?’ He was a great simplifier on this issue.” He retorted to his father: “The drowning man clinging to his plank is allowed, by all the rules of natural, objective, universal justice, to make room for himself on the plank, even if in doing so he must push the others aside a little. Even if the others, sitting on that plank, leave him no alternative to force. But he has no natural right to push the others on that plank into the sea.”

What would your father think if he could hear you now? “He would be very angry with me – no doubt.” Is this, in part, an Oedipal revolt? Oz frowns a little. “There is an element of Oedipal revolt in every father-son relationship, including the relationship between me and my father.”

But there was one conviction he inherited from his father and has always retained. They both saw religion as an “archaic dust”, a bizarre leftover from a more primitive, less rational age. So when the settlers began to seize the West Bank as part of a Messianic plan to reclaim the entire biblical land of Israel, Oz saw it with horror as an attempt “to push Judaism back through history, back to the Book of Joshua, to the days of the Judges, to the extreme of fanatical tribalism, brutal and closed.”

The tragedy is – he believes – that these people believe they are motivated by the best in human nature. He wrote in his novel Black Box: “It is neither the selfishness nor the baseness not the cruelty in our nature that turns us into a species that destroys itself. We annihilate ourselves (and shall soon wipe out our entire species) precisely because of our ‘higher’ longings, because of the theological disease.” The settlers believe they are saving us, even as they drag their tribe towards hell.

“The Jewish people has a great talent for self-destruction,” he sighs. “We may be the world champions in self-destruction... [caused by] our characteristic demand for perfection, for totality, for squeezing our ideal to its last dregs or to die trying. [Look at] the history of the ancient Hebrews – they were suicidal by being extremely extremist and fanatical, by not compromising with reality, by not being ready to tolerate a Roman yoke for a while in order to survive and stay in the country. We lost our country in 70AD because we were impatient and we couldn’t tolerate a lasting Roman yoke. That was a gross mistake.” Likewise, the settlers now seek to seize all of the historical land of Israel – and in so doing, they prevent a two-state solution and could condemn Israel to a slow death.

Then, suddenly, he leans forward. “But let me share with you some good news, because you normally get only the bad news from the Middle East on the press and the media. The good news is that the vast majority of the Israeli Jews and the vast majority of the Palestinian Arabs know, in their heart of hearts, that at the end of the day there will be a two-state solution. They know it. Are they happy with it? They are not happy with it. Will they be dancing in the streets when the two-state solution is implemented? They will not be dancing in the streets. But they know... There is lack of bold leadership on both sides. But the two-state solution remains the only way out.”

He has been offering this beautiful, rational vision for 40 years now, and I have happily repeated his lines. But aren’t there days when he despairs? Aren’t there days when he agrees with Boaz, one of the characters in Black Box, who says: “In the end the Jews will finish [the Palestinians] off or they’ll finish each other off and there’ll be nothing left in this country again except the Bible and the Koran and the foxes and burned ruins”?

He smiles. “I like Boaz a great deal – I think he’s quite a character. But I don’t share his pessimism. I think a two-state solution is inevitable. The Israeli Jews are not going anywhere. There are five and a half million of us, and we’re not going anywhere – we don’t have anywhere to go. The Palestinian Arabs are not going anywhere, either – they don’t have anywhere to go. We cannot become one happy family, because we are not one with the Palestinians and we are not family and we are not happy, either. We are two unhappy families. So, it’s about turning the house into a semi-detached house. A two-family unit. There is simply no alternative to this. Now, this make take long or may take short. But it will happen.”

And then our discussion of his passionate attempt to rescue his country returns, obliquely, to the question of the mother he could not rescue. He believes the answer to the conflict – the temperamental solution – lies in the author she loved, even as her headaches raged and her will to live waned. “At the end of a Shakespeare tragedy, the stage is strewn with dead bodies, and maybe there’s some justice hovering high above. A Chekhov tragedy, on the other hand, ends with everybody disillusioned, embittered, heartbroken, disappointed, absolutely shattered, but still alive. And I want a Chekhovian resolution, not a Shakespearian one, for the Israeli-Palestinian tragedy.”

III. Operation Cast Lead

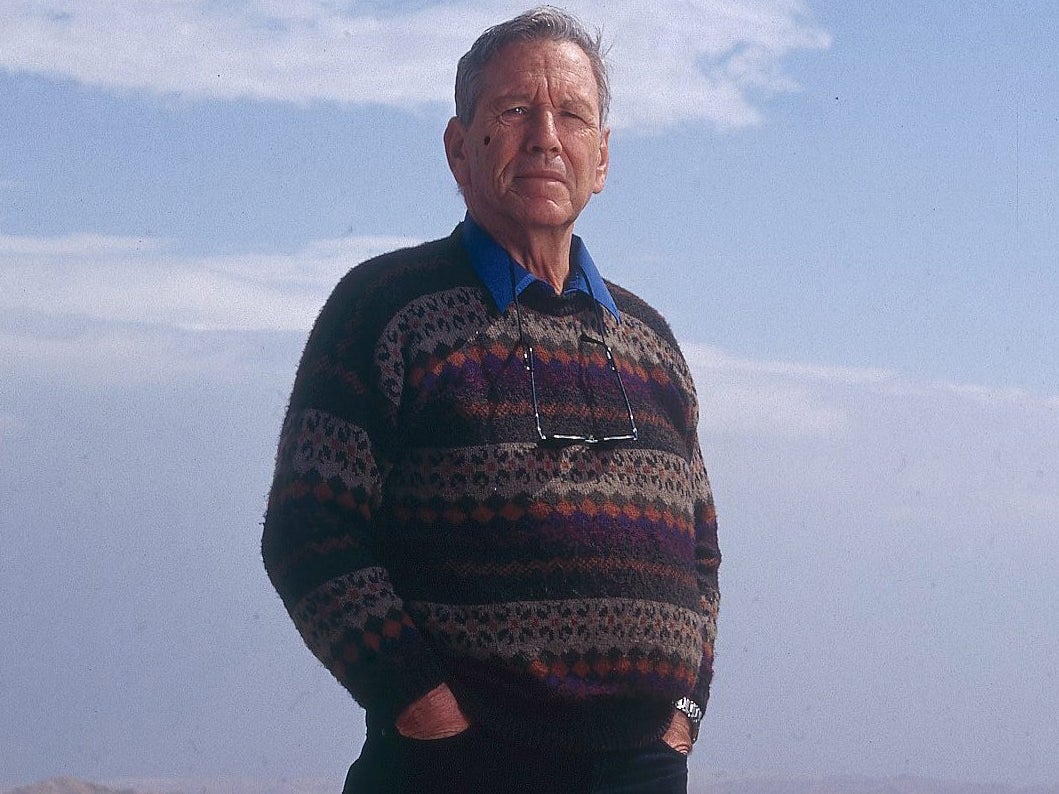

Today, Oz lives on the edge of the Negev desert, and it strikes me he has come to resemble it – his manner is dry and slow and vast, and he seems to look down on history from the perspective of thousands of years.

Why is Oz capable of understanding the dark ambiguities – and the need for compromise – when so many of his Netanyahu- and Lieberman-voting countrymen aren’t? “See, I get up every morning very early, I drink a cup of coffee, I sit myself by my desk, and I start imagining, ‘What if I was him? What if I was her?’ That’s how I make a living: by imagining the other. I imagine the other. That’s my professional life. And my hobby, as well: I sit myself in street cafés, and when I have nothing else to do, when I’m waiting for someone...” He looks out over the café we are sitting in now, and smiles. “I look at the other guests in the cafés and try to imagine their life, who they really are, what are they talking about at that faraway table?

“So that’s what I do. It’s easy for me. It’s much harder for ordinary people who are not writers, who are not novelists, to imagine the other in times of war, or even in times of a family feud. In this I belong in a minority. Most people don’t bother.” He repeats himself, with a shake of disdain: “Most people don’t bother.”

This, he adds quickly, isn’t unique to Israel. “It is caused by anger, my friend. Anger. War begets anger and hatred and resentment. Very few people in Britain could pay any attention at all to the ordeal of Dresden and Leipzig. Very few people at the end of World War Two in London would pay any attention to the suffering of the innocent civilians in those cities.”

And yet, and yet... it seems that Oz has failed, at last, to hold himself to the high standards he has set. He initially supported Operation Cast Lead – the bombardment of Gaza that killed more than 1,400 people, 40 per cent of whom were children – even though he says he knows, from his own experience, that it will make the children of Gaza dream lunatic dreams of revenge. I ask him why. “Hamas fired some 10,000 rockets on southern Israel, where I live. And I don’t think any country in the world would simply turn the other cheek to that. I don’t think England would restrain if anybody showered Yorkshire with 10,000 rockets. So, an Israeli response was understandable and acceptable, in my view. The dimensions of the response, the disproportion of the response, is something which I severely criticise.”

But use your own test – of seeing the other side; of empathising. Using the same logic, you can ask from the Palestinian perspective – what country could tolerate being violently occupied for 40 years, then having part of its territory blockaded and semi-starved, just to punish it for how it voted in a democratic election?

He uncharacteristically changes the subject, and tries to blame somebody else. “Well, I’ll tell you something about this blockade. Gaza borders with Egypt. There was no reason why the Egyptians would not provide Gaza with whatever it needs. And there is very little reason for Israel to provide Gaza with what it needs. After all, Gaza is firing on Israel... If Egypt and the rest of the Arab world wanted to invest in Gaza and to rebuild Gaza and to raise the standard of living in Gaza, they could have done it.” Yet Oz knows it is Israel that puts vast pressure on Egypt – especially through the US – not to do that. Israel’s own security services said Hamas would extend the ceasefire if Israel agreed to ease the blockade. Wouldn’t that have been better? Wouldn’t fewer children now be dreaming of shooting rockets at Tel Aviv?

Oz – for the first time in our interview – seems unsure. “I don’t know. I think we tried. If we tried hard enough, I don’t know. I really don’t know.” He looks down, then away.

Then he says more confidently: “I think in the last days before the Israeli attack on Gaza, the firing of rockets increased to about 80 rockets a day. And our casualties, and our homes destroyed, and there was the suffering of close to one million Israelis who have to live in underground shelters. No government could tolerate this. No government could simply turn the other cheek.”

But the Palestinian side was suffering even more horribly – using your logic, they, too, have a right to fight back and bomb. “I could understand and justify, and justified, a limited, proportionate, measured, cautiously targeted Israeli military response – not a full-scale war. You see... I said many times, and I’ll say it again – I’m a peacenik, not a pacifist. Yes, the pacifists believe that the ultimate evil in the world is war. I believe that the ultimate evil is not war but aggression, and aggression sometimes has to be blocked by force. Hence the difference between a peacenik and a pacifist.”

It is another wriggle. I’m not advocating pacifism – I’m saying this specific war was a bad idea. As if to soothe me, he says: “I think there should be a thorough judicial interrogation of the occurrences in the Gaza war. The Israeli judiciary is independent and bold and I think there should be a thorough, comprehensive interrogation.” He then says that “in principle”, Israel should negotiate with Hamas. “If Hamas is ready to talk to Israel, Israel should talk to Hamas right away. Absolutely. Absolutely. Of course, we need to. It’s difficult to compromise with Hamas because Hamas maintains that there should be no Israel at all. Not even I can propose as a compromise that Israel exists Mondays, Wednesdays and Thursdays. But the moment Hamas shows the slightest inclination to recognise Israel, I would talk to it – of course I would.”

The he surprises me with a bold prediction. I ask: can you imagine Bibi Netanyahu shaking hands with the Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh on the White House lawn, with Obama smiling in-between? He beams. “Absolutely, yes. Absolutely, yes. Absolutely, yes.” He adds: “Don’t swear an oath about Netanyahu not delivering the two-state solution. So far, we have seen almost every right-wing Prime Minister making surprising concessions for peace. Begin over Sinai and the peace with Egypt; Sharon in evacuating the Gaza strip; Netanyahu himself over the Hebron concessions. So, I don’t know. I cannot read his mind; I am sure he does not know yet what he is going to do. But it may well be that reality will be stronger than him, that he will sense the mood of the majority of the Israeli people and surprise us.” He has met Netanyahu “a few times”, and says: “Deep down below, he strikes me as an opportunist, and that’s not necessarily a bad quality under the circumstances.”

Oz and Netanyahu come from similar backgrounds: right-wing revisionists in a socialist country, demanding tougher, harder, crueller policies. Can you imagine a world where you ended up like him? “Yes, yes,” he says. “Well, the question is – would he end up like me?”

What does this support for the attack on Gaza – and the initial bombing of Lebanon in 2007 – suggest about Oz? Is there a desire to be an easy, unconflicted part of the tribe – to belong – at last? Is his empathy running out as rockets rain close to his home? In his latest, tender book, Rhyming Life and Death, a middle-aged novelist wanders the streets of Tel Aviv, feeling disconnected from his country. The character admits to “a profound sadness that he is always an outsider”.

Do you feel this, Amos? There is a long pause. “I would say yes,” he says. But every follow-on question I ask to tease this out only prompts a subject-changing anecdote about something else. The loneliness of the exhausted, wavering peace campaigner is something he doesn’t want to discuss. And so the boy who ran away from his suicide-scarred home at 14 to become a left-wing icon might be allowing flickers of his father’s voice to break through – at last, after all this time.

Amos Oz, Israeli writer, born 4 May 1939, died 28 December 2008

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments