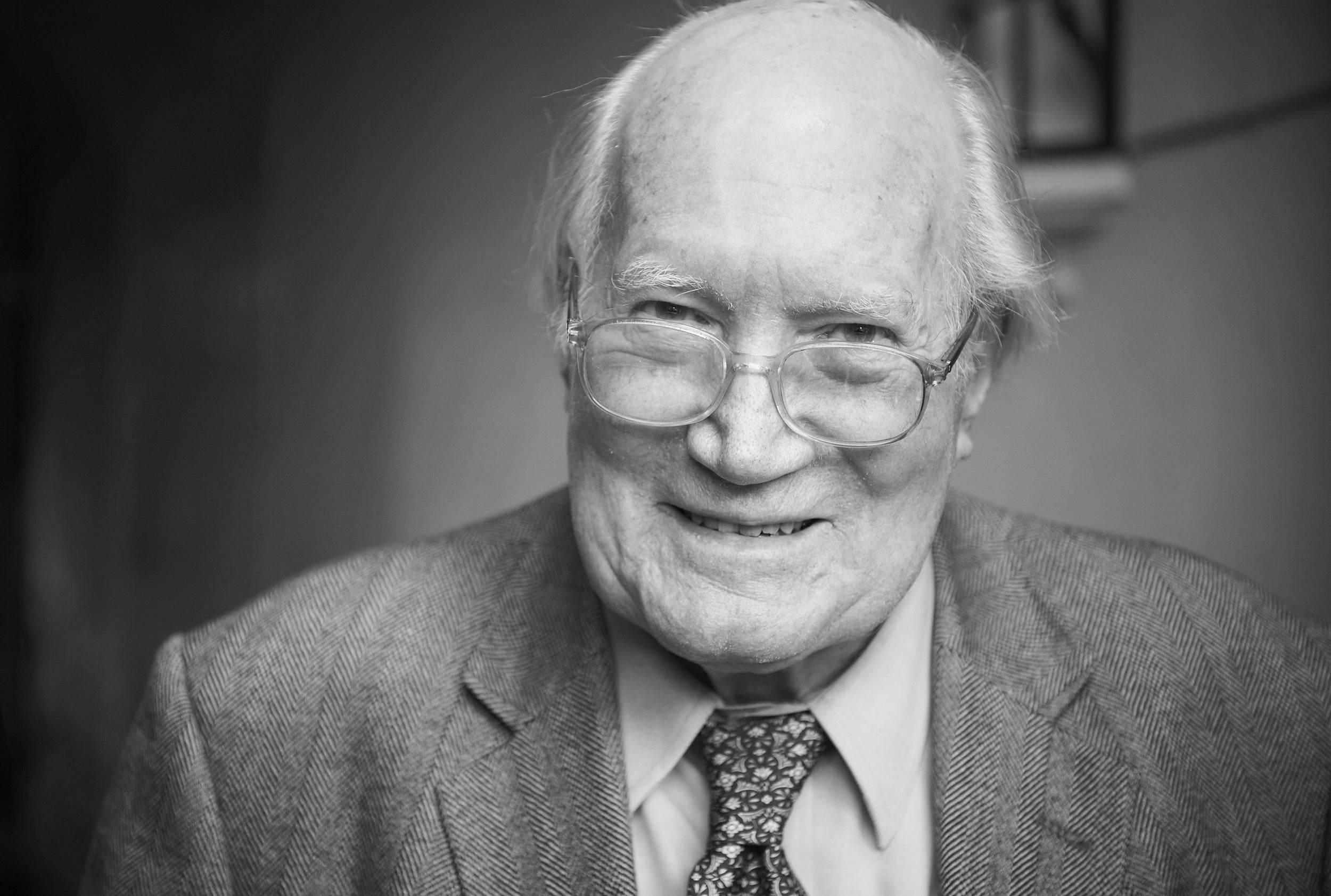

Sir Alistair Horne, obituary: war historian whose work was widely read and admired

A spy in Palestine and Cairo during the Second World War, Horne’s oeuvre included books on French history, the Algerian independence struggle, Harold Macmillan and Henry Kissinger

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1939, Alistair Horne, then a crafty boy of 13, struggled all summer long trying to build a home-made wireless. For weeks he twiddled the knobs, failing to catch a sound.

Then, on 3 September, a voice finally came through: that of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, declaring war on Germany. But Horne was too excited to really listen. He flew down the stairs, shouting “Daddy, wonderful news – it works!” His father replied, “Later, old boy, later.”

That same day, news came through that a passenger liner had been torpedoed by a German U-boat. Of that moment, Horne wrote: “It had begun. I had suddenly grown up.”

War was to play an outsize role in Horne’s life, as a soldier, a spy, a reporter and a widely read historian of conflict.

But the immediate impact the Second World War had on his life was to uproot him from England. Being sent off to New York for safety turned out to be a godsend for the young Horne, whose upper-class childhood – marked by private-school bullying and the loss of his mother at the age of four – had been “rather miserable”.

Still, Horne was eager to take part in the war effort, and as soon as he was old enough to do so returned to Britain and joined the Royal Air Force. His dreams of flying a Spitfire were frustrated by poor eyesight, however.

He was then posted to the Middle East, where he worked as a spy in Palestine and Cairo under Maurice Oldfield, who would later head MI6.

After the war, Horne studied English at the University of Cambridge before becoming German correspondent to The Daily Telegraph in 1952. He made his name there with the scoop that the Allied forces were controversially returning to the Krupp family the factories they had confiscated at the end of the war. But Horne’s journalism was a cover for “extracurricular activities”, namely, Cold War intelligence gathering for Oldfield.

Frequent trips made at the time from Bonn to Paris, past the battle sites of Sedan and Verdun, first gave him the idea of writing about history, and in particular the history of French wars.

Through the 1960s he produced a trilogy on Franco-German conflict: on the siege of Paris in 1870-71, the battle of Verdun in 1916 and the defeat of France in 1940.

But his most notable contribution to historical research was his work on the Algerian War of Independence, A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962, for which he struggled to access Algerian sources but compiled many accounts on the French side. “They wanted to talk, talk, talk,” he said of the French survivors of the war.

Horne further wrote a biography of Harold Macmillan, another of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, and an account of a year in the life of Henry Kissinger. He also wrote two memoirs.

Horne was more willing than some contemporary historians to consider “the lessons” of history. Both Ariel Sharon and George W Bush read his history of the Algerian War while in office, to inform them in their Palestinian and Iraqi wars, respectively. Horne thought neither leader acted as history should have led them to.

He is survived by his wife and three children, as well as by a fellowship in his name at St Antony’s College, Oxford, in support of budding historians.

Reflecting on his life late last year, Horne found unity in his varied work: “There’s a curious correlation between being a spy, a journalist and a historian,” he said. “The whole thing is to ask questions and doubt, be suspicious.”

Sir Alistair Horne, born 9 November 1925; died 25 May 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments