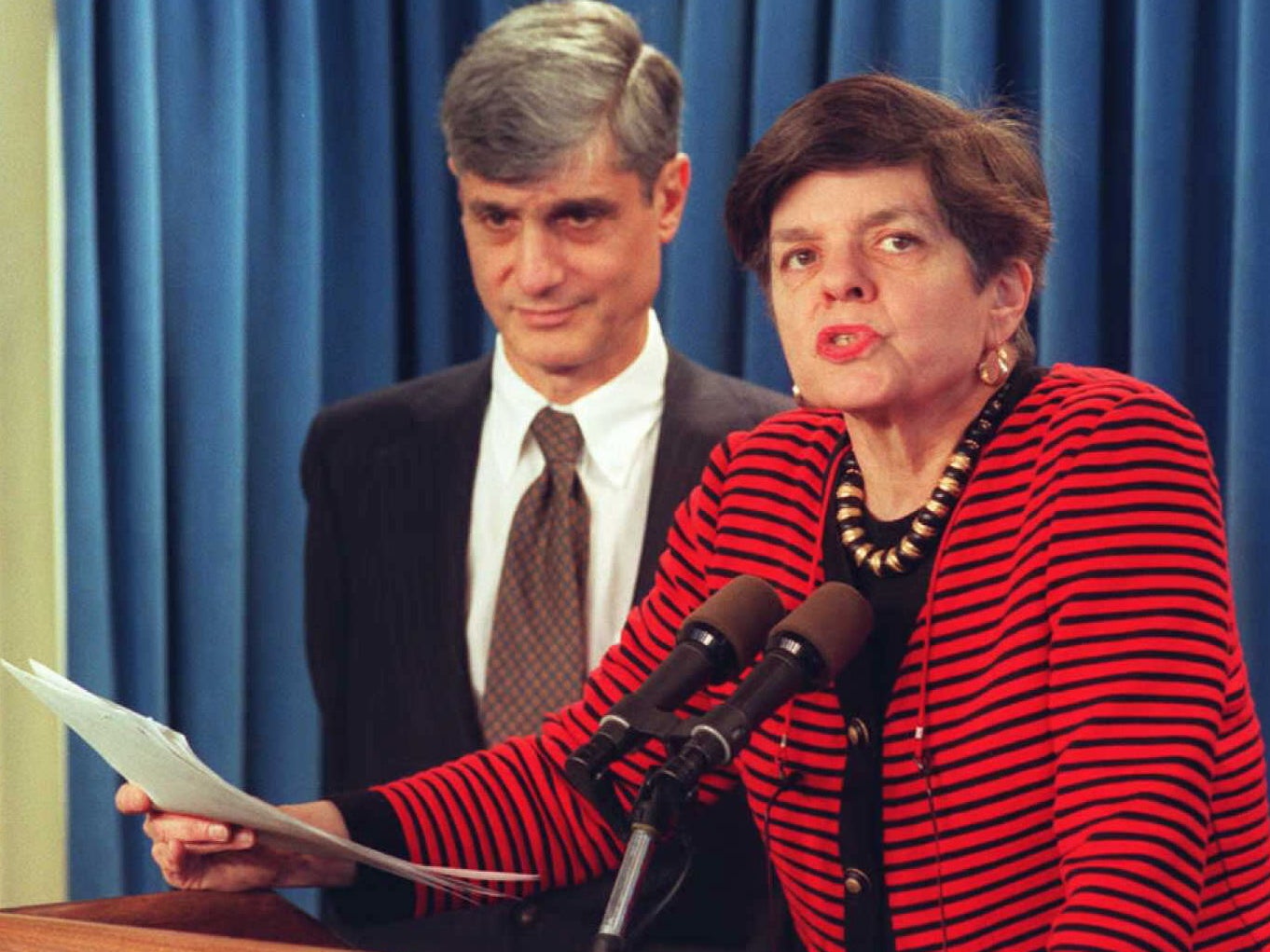

Alice Rivlin: Economics intellectual and first woman to lead the White House budget office

The fiscal expert battled sexism throughout her life to eventually rise to the top in Washington

In 1952, when young economics graduate Alice Rivlin applied to a post-graduate course in public administration, she was turned down on the grounds that she was a woman of “marriageable age”. Four decades later, in 1994, Rivlin made history when she became the first woman to head the White House’s Office of Management and Budget under Bill Clinton. Later she was the first woman deputy chair of the Federal Reserve.

Rivlin, who died aged 88, was born Georgina Alice Mitchell to Georgianna Peck, a national officer of the League of Women Voters, and nuclear physicist Allan CG Mitchell. Though she was born in Philadelphia, Rivlin grew up in Bloomington, Indiana. She studied at Bryn Mawr College, originally hoping to become a historian. A short economics course at Indiana University persuaded her to change direction.

Thwarted in her ambition to study public administration, Rivlin did indeed get married in 1955. However three years later, she earned a PhD in economics from Harvard’s Radcliffe College and joined economics think tank the Brookings Institution. It was while she was a researcher on budgetary and social programmes there that President Lyndon Johnson invited her to be deputy assistant secretary for program analysis at the US Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

Rivlin would have a long association with the Brookings Institution, returning again and again throughout her career. She also taught at Harvard University, The New School and George Mason University. She was visiting professor at Georgetown University’s Public Policy Institute. Rivlin also authored three books: Systematic Thinking for Social Action (1971), Caring for the Disabled Elderly (1988) and Reviving the American Dream (1992).

Twenty years after she missed out on a post-grad course for being the wrong age and the wrong sex, Rivlin faced sexism head-on again when she was offered the chance to head new government agency, the Congressional Budget Office. The CBO had been created in response to the Watergate scandal, as a check on the administration’s Office of Management and Budget.

Despite her impressive CV, Rivlin faced opposition. Recalling the situation on NPR’s podcast The Indicator, Rivlin said, “The head of the House Budget Committee [Oregon Democrat Al Ullman] was actually rather sexist, and he'd been heard to say that over his dead body would a woman have this job.”

Ironically, it was a sex scandal involving another congressman, Wilbur Mills, and a stripper called Fanne Foxe, that cleared the way for Rivlin’s appointment. When the disgraced Mills had to leave his position on the “Ways and Means Committee”, the resulting reshuffle meant that Ullman, who had been so against having a woman on the budget committee, was moved into Mills’ vacant spot. The new chair of the budget committee, Democrat Brock Adams, was only too happy to have Rivlin on board. In an interview years later, Rivlin claimed: “That’s how I got my job. I owed my job to Fanne Fox.”

But it wasn’t chance that kept Rivlin at the CBO for the next eight years. While in the position, she changed the way Washington made policy, emphasising the importance of analysing the economic impact of new bills. A centrist Democrat, Rivlin was careful to remain non-partisan throughout her CBO tenure though she was a critic of Reaganomics.

After her stint at the CBO ended in 1983, Rivlin was awarded a MacArthur “genius grant” and became president of the American Economics Association. Ten years later, she became Clinton’s deputy director of Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Then in 1994, she cracked the glass ceiling when she became director of the OMB. She did it again when in 1996 she was made a governor of the Federal Reserve and later its vice-chair.

Rivlin is also revered for her work on the DC Financial Responsibility and Management Assistance Authority, dragging the declining and bankrupt district, which was riddled with crime, back into solvency in the late Nineties.

Rivlin continued to work into her eighties. Described as “hawkish” on debt reduction, in 2010, she co-chaired a Debt Reduction Task Force backed by the Bipartisan Policy Centre in Washington, DC. Shortly after that, she was one of President Obama’s nominations to the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (also known as the Simpson-Bowles Commission).

In 2013, Rivlin was persuaded to dance the Harlem Shake in a video for The Can Kicks Back, the millennial arm of the controversial lobbying group Fix The Debt, which advocated austerity measures such as slashing social security and Medicare to reduce the national deficit. Rivlin told her young audience, “There's no dancing around the fact that more needs to be done quickly to put our future debt on a downward track. But our leaders need to hear from you.”

In her later years, Rivlin’s contribution to public life was honoured with a string of awards. In 2008, she received the Moynihan Prize. That same year, she was named as one of the greatest public servants of the past 25 years by the Council for Excellence in Government. In 2012, she was given a Foremother Award by the National Research Centre for Women & Families. She was awarded $100,000 by the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research for her career-long dedication to improving lives through economic policy.

Rivlin had three children with her first husband Lewis Allen Rivlin. Their marriage ended in 1977. Rivlin married her second husband, economist Sidney G Winter, in 1989. She is survived by her husband, her daughter Catherine and sons Allan and Douglas, two stepsons and five grandchildren.

Alice Rivlin, American economist, born 4 March 1931, died 14 May 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments