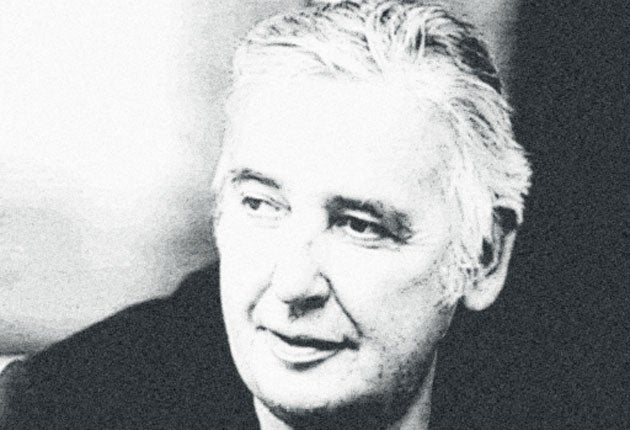

Alan Watkins: A romantic at heart

Alan Watkins was a master columnist whose intellect illuminated the worlds of politics and sport. At his funeral yesterday, Welsh rugby hero Gerald Davies paid tribute to his friend's passions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is a great privilege to have known Alan Watkins and I am honoured to have been asked to pay tribute to him today and to recall the wonderful and unique contribution that Alan made in his writing on rugby football, the passion for which was born out of his heritage in his beloved Wales. He lived most of his life outside of Wales but he cared deeply and had a special place in his heart for Wales.

Alan was of a generation, in Wales, when with a sense of opportunity, even of emancipation, he found he might fly and soar above and to progress beyond what were the social inhibitions and educational restrictions – which were only beginning to loosen – in that time and of that place. Education, education, education has been the mantra of a recent age but the one word recital would, as likely as not, have reverberated around the hearth of Tregarn in Tycroes many decades ago and, then, as in every family in a mining village, infused with a greater sense of potential liberty. It was the way, the only way, "to get on" as they say.

This sense of hope that education gives is meaningful nowadays but how much more potent and poignant it was then in Alan's day in that y filltir sgwar, as they say in Welsh, which is that precious square mile, familiar and well-explored, to everyone belonging to a small community. Education was the way out to a different world, to allow for different hopes and dreams, of ambition and of "getting on" beyond the limitations of a recurring cycle of oppressive industrial jobs and into a different "trade".

Alan's parents had managed to release themselves from the previous generation who were colliers to become qualified teachers, while Alan of the next generation moved further again.

"Upwardly mobile" may not have meant much in Tycroes in the 1940s other than perhaps the journey at the end of the day's shift from the anthracite seam and the lift up from the pit to the fresh air once more. It is nevertheless quite a climb, and certainly not a short walk, from where Alan was born – partly rural, partly industrial, largely indifferent to the outside world – to take the journey, of enterprise and resolution, and through extraordinary talent, to conquer and to find his particular and specialised niche in Fleet Street.

A grammar school boy at Amman Valley, he was of Exhibition class to enter Queen's College, Cambridge but got no award because he had already received – so the then-tight-fisted College maintained – a scholarship from the Carmarthenshire County Council. And so finally – to use a phrase he once applied to the New Statesman before embarking on his own journalistic path – to attain for himself a kind of "metropolitan omniscience" in the field of political commentary.

His love of politics and rugby was nurtured in such a Carmarthenshire community, where the two topics represented the basic constituents of any worthwhile conversation, and at his father, David John's, knee going to watch rugby matches together, Alan in shirt and tie and balaclava ... an arresting image, I have to say, of Alan, representing for the last time perhaps when his tie might have been neatly knotted and shirt appropriately buttoned.

From this early rugby experience the following comic observation was made and to quote from one of Alan's pieces: "It is disputed whether the Swansea or the Llanelli crowd were the more knowledgeable. On the whole Llanelli's were the more serieux, Swansea by comparison a cosmopolitan, fly by night, even raffish kind of place. I see them now ranging (for it is a mistake, he added, to suppose that class distinction does not exist in Wales) – ranging – from the miners in their off-duty uniform of single-breasted fawn mackintosh, white silk scarf and flat cap to the more preposterous voters in the stand, schoolmasters and suchlike, in heavy double-breasted overcoat, paisley or striped scarf, trilby hat and leather gloves looking rather like members of the Supreme Soviet about to take the salute at the May Day parade".

An article ostensibly about rugby, and Alan would invariably provide a humorous observation, coming unexpectedly from somewhere from left field. Within the rugby commentary there would emerge an observation of something else, more personal, from another field of human activity which would transform the piece into something beyond simply the rugby view and which would linger longer in the memory.

Alan would have listened, as any child would, to the adults' indulgent talk after chapel, such talk as dissected the current political mood and the rugby goings-on in Stradey Park, Llanelli, or Wales' rugby international matches in St Helens, Swansea.

His parents, David John and Violet, were especially influential. If he inherited his mother's love of the English language, he followed among other matters his father's observation, by and large, of having no tolerance for "swank", "pretence" and "nonsense".

To these three conditions he held most faithfully although he allowed a certain leniency and licence in rugby. Still, if "pretence" and "nonsense" could not be spared, a bit of "swank" was permitted in rugby especially for the privileged outside half. A bit of swagger is a precondition, essential even, to anyone with ambition to wear the number 10 jersey especially for his native land, as he would say, for Wales. Which is why he was thrilled with the player with a bit of the devil in him, a maverick spirit, a will'-o'-the-wisp, noble and brave on the cusp of fear in the face of the mighty muscles that stood in front of him.

We recognised the "beast" at the coalface of the game as well as the boys of summer with the wind in their hair. He appreciated – as the French say of their team – that their best is made up of the butcher and the artist, the piano shifter and the piano player. Alan was quite pragmatic of the imperatives required of the rough and tumble of rugby even though he remained a romantic of the game at heart.

With the French in mind he admitted that apart from his countrymen – naturally – France was his favourite team. And supported them. Why? Because they play entertaining football, he claimed. But there were occasional disappointments when he did not, as was the case apparently in March 1989. That season he proposed a neutral position. And why the change of allegiance?

I quote from Alan again.

"What has happened?" Alan asked himself. "I have not changed, but the French have. In large French towns see a McDonald's hamburger dispensary among the traditional cafés, bistros and bars. The young crowd are into the new place; understandably in a way. Because they wish to be up to date. Jacques Fouroux, the French coach, has brought the philosophy of McDonald's to French rugby. He preaches the gospel of success, which is to be achieved through saturation coverage, through uniformity, and through bulk."

Another piece I cannot resist including from Alan. He was present at a press conference after an International match between France and England. Of Jacques Fouroux he wrote: "He seems to speak French better than his equivalents on the other side speak English. He certainly speaks English better than they speak French. However he chose to address the press in his native tongue. He was wearing a lilac silk handerkerchief in the top pocket of his dark blue blazer. On the English side such sartorial extravagance, even decadence (lilac being the colour of Oscar Wilde, he observed, always more appreciated across the Channel) would doubtless be prohibited as prejudicial to good order and rugby discipline."

His rugby pieces were always a joy to read, uncertain what nuggets we might find to illuminate what might otherwise represent harsh and often perhaps dull play.

He enjoyed rugby and did not condemn as others of his generation have the so-called "modern game", although inevitably he chuckled, accompanied with a wry observation as he would do on anything that appeared exaggerated or false. Overemphasising fitness, he felt, might take the enjoyment out of a game that required the right balance between grimness and gaiety, fitness and flair. "Fitness is necessary," he said. "Don't misunderstand me. Rugby after all cannot be enjoyed if you are gasping for breath or on the verge of collapse. But it cannot be enjoyed either if it is regarded as a sort of penance." To my knowledge I don't think a fanatical fitness regime formed any part of Alan's lifestyle.

What mattered was his writing, mattered to us all – his point of view and the manner of that expression of that point of view – with the occasional old-fashioned phrase, tactically placed and poised, for resounding effect. I shall not say we shall not see his like again. For I would like to believe that we will. There could be no poorer way of paying homage to the memory of Alan Watkins than for us to assume that his style of writing in his much-cherished English language, the ease and effortlessness of the expression, the good humour of his mood, his generosity of spirit his convivial company, the wisdom and the lack of malice, has perished. His legacy should remain an inspiration to us all and to be fervently pursued. So that we might say over breakfast in days to come as we did of him: "I wonder what Alan Watkins has to say?"

Diolch yn fawr, Alan, am y boddhad, yr eglurhad a'r gorfoledd am eich gwaith. O hyn ymlaen fydd na wacter mawr wrth feddwl na allwn ddarllen erthyglau Alan Watkins rhagor.

For those of you unfamiliar with what I've said – clearly a very few of you! – I've simply said how I will miss his weekly column and the essential, unmissable words – and so grateful to have known you, Alan, and treasure the memories.

Born of the sun he travelled a short while towards the sun. And left the vivid air signed with his honour.

This is an edited version of an address read at Alan Watkins' funeral yesterday at St Bride's Church, Fleet Street, City of London

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments