Alan Davie: Scottish painter whose kaleidoscopic canvases took inspiration from improvised jazz and free verse

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Few post war British painters scaled the same creative heights or achieved the wide international recognition that Alan Davie enjoyed from an early stage in his long, extremely productive career.

Though it proved enduring, the early fame was followed by years of relative neglect – the charged gesturalism and vivid colour of earlier work always proving more popular than the later, more designed "oeuvre" that was close in style to magical realism. The halcyon 1950s saw large, bold and energetic compositions in dialogue with both American abstract expressionism, many of whose leading figures Davie met in New York, and the so-called "middle generation" in St Ives.

Alan Davie was born in Grangemouth, Scotland in 1920. His father, a Glasgow-trained painter and etcher, encouraged art and at 17 Alan entered Edinburgh College of Art, studying there between 1937 and 1941. Davie's work developed in the sympathetic climate of an Edinburgh art scene dominated by the Francophile painters John Maxwell, one of his tutors, William Gillies and Anne Redpath.

Davie's virtuoso talents made him question the traditional boundaries of easel painting, however, and he experimented with textile design (carpets were later made to Davie's distinctive designs), jewellery-making, which he later taught at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, London and pottery. While serving in the Royal Artillery between 1940 and 1946, he wrote poetry and played jazz, activities that informed the mature paintings, whose spontaneously handled paint directly paralleled the free association verse and improvised jazz that inspired him.

Davie's first big break came in 1948 when he travelled in France, Italy and Spain. Accompanied by Janet "Bili" Gaul, a potter whom he married in 1947, Davie chanced on the Biennale in Venice, the first since the war, where he encountered the work of Picasso, Miro and Moore. Crucially, he met the renowned patron Peggy Guggenheim, who purchased a painting, Music of the Autumn Landscape, and introduced Davie to the work of the emerging New York School painters, among them Pollock, Motherwell and Rothko. She also introduced him to the Gimpels, whose London gallery, Gimpel Fils, would become the artist's principal showroom for the rest of his career.

The exhibiting successes that gathered pace during the 1950s – in 1958 alone he had important retrospective exhibitions at Wakefield Art Gallery, the Whitechapel, London and the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, and exhibited in the 29th Venice Biennale – were accompanied by teaching at the Central School between 1953 and 1956 and by his securing of the Gregory Fellowship in Leeds between 1956 and 1959.

The early expressionism of The Saint (1948) was replaced by a freer, less iconic style of distorted or writhing biomorphic imagery. Like early Jackson Pollock and Arshile Gorky, Davie used archetypal symbols and complex biomorphic imagery dredged from the subconscious and wildly improvised onto the canvas. Although afterthoughts, the titles (Fate of the Lovely Dragon, Bull God, Entry of the Fetish) had an appropriate free-association poetic ring. The luscious oranges, viridians, reds, yellows and pinks highlighted a Scottish colourist in the grand Francophile tradition. Recurring room-like backgrounds recalled the oppressive closeted interiors of Francis Bacon but provided a necessary foil and structure to the wild outpourings of the foreground.

The year 1956 was pivotal; a one-man exhibition at Catherine Viviano Gallery, New York, introduced Davie to a vital American audience. Habitually independent and socially retiring, Davie did not join the boozy Cedar Tavern soirees of his New York co-freres, though the leading abstract expressionists attended his show and he stayed with Pollock and Lee Krasner at their Long Island retreat. He warmed to the Pollocks, Davie recalling that Pollock's legendary hellraising was socially manipulated and encouraged by malevolent drinking companions.

Davie's links with New York, St Ives and the Cobra expressionism of Appel and Jorn notwithstanding, the work developed in a unique and individual way. As Robert Melville wrote, the "sombre pictures which suggest the corners of imaginary rooms'' soon became "swarming grounds for signs and symbols.'' Perhaps Martyrdom of St Catherine (1956) marked the transition from early gesturalism towards the later sharpening and hardening into coherent symbols; the sacrificial altar, wheel, crosses and pictographic rectangles in this picture were set against a flat and uniform background. The religious connotations were never ethnocentric, however: he introduced symbols and ritualistic signs picked up from Zen, yoga, shamanism, Navajo Indian sand painting, Arabic manuscripts and Jain cosmology.

The artist as seeker sat well with an intrepid landscape explorer, much in keeping with the Cornish "middle generation" (he kept a house near Land's End, away from the competitive St Ives cauldron). From the mid-1970s he also visited St Lucia in the Caribbean every year, where he also kept a house for some years and the exotic imagery of the later work stemmed from the Island.

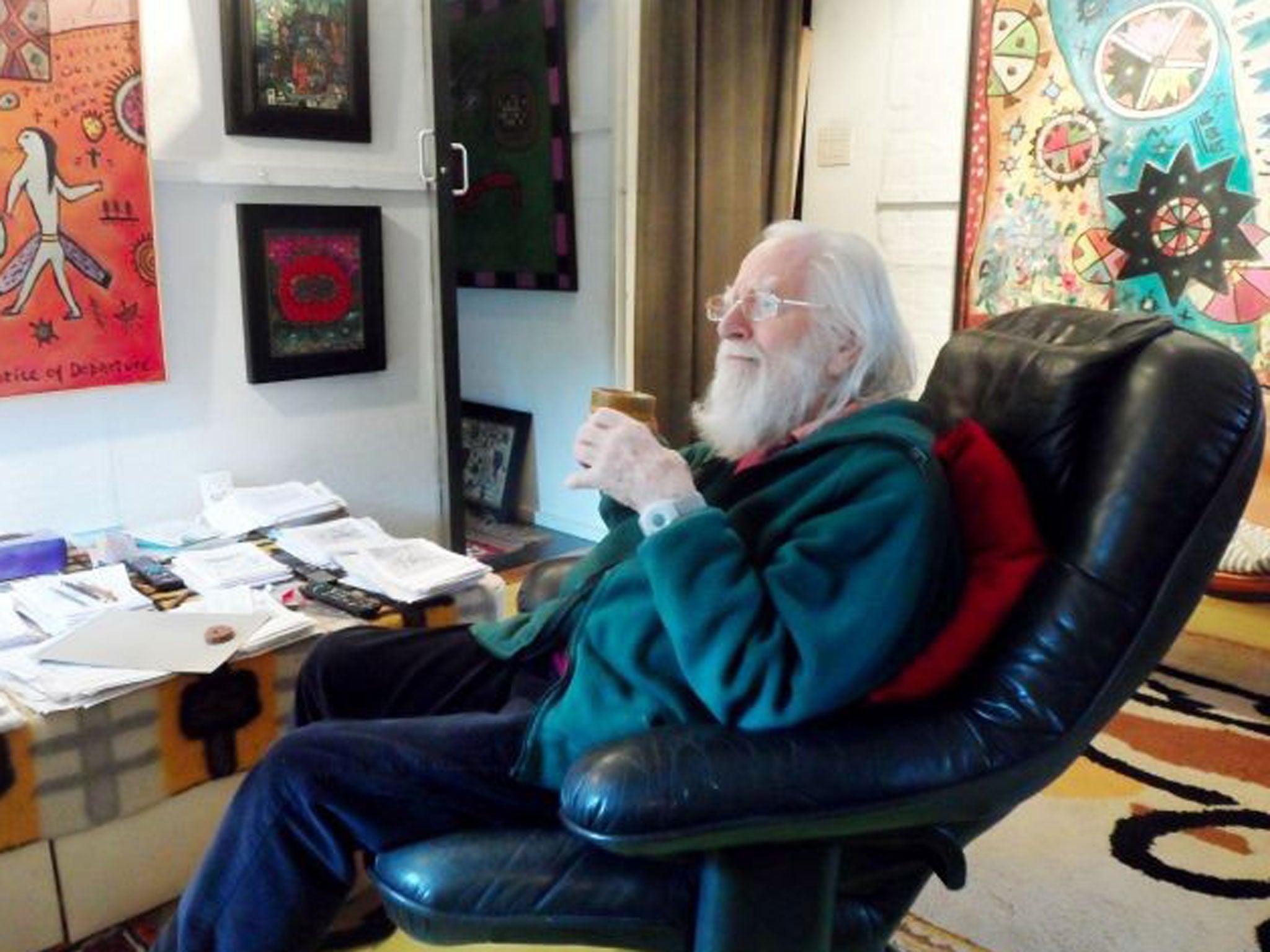

Davie retained a long beard and hair that gave him the perennial look of an ageing hippie – and like a hippie, Davie also loved music, his tastes again admirably wide to encompass both modern jazz and classical. The Alan Davie Music Workshop made records in the early 1970s and in 1971 gave public music recitals at Gimpels, at the Tate Gallery and at the Camden Arts Centre.

In 1974 Davie began designing tapestries in editions of six for Gimpels and in 1977 produced a mosaic for his hometown of Grangemouth. A 1978 touring exhibition across the south-west tellingly did not take in Cornwall, though a Davie retrospective was put on at Tate St. Ives in late 2003. During the 1980s and 1990s he enjoyed many solo shows in Britain and abroad. A 70th birthday retrospective exhibition at the McLellan Galleries, Glasgow in 1992 toured to Edinburgh and Bristol before being taken to Belgium and South America by the British Council.

Davie's work was championed by art historians and fellow poets and musicians alike – Alan Bowness's 1967 monograph sitting comfortably alongside studies on the artist by the poets Michael Horovitz (1963) and Michael Tucker (1997). Jung's Psychology and Alchemy was his bible, from which Davie extracted archetypal imagery.

An exhibition of Davie's work opens at Tate Britain on 14 April.

Peter Davies

Alan Davie, painter, musician, teacher: born Grangemouth, Stirlingshire 28 September 1920; married 1947 Janet 'Bili' Gaul (died 2007, one daughter); CBE 1972; died 5 April 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments