Adrian Kantrowitz: Pioneer of heart transplants in babies and of heart prosthesis implantation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

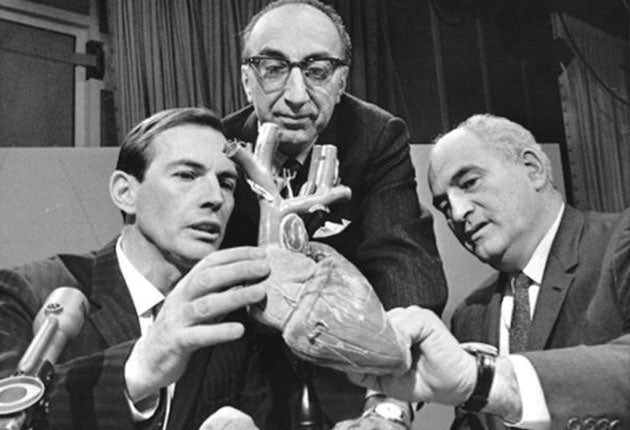

Your support makes all the difference.Adrian Kantrowitz was the New York surgeon who performed America's first heart transplant – and the world's first in a baby. On 6 December 1967, three days after Christiaan Barnard's pioneering surgery, Kantrowitz transplanted the heart of a donor, an 18-day-old baby with spina bifida who had no chance of living, into a two-day-old with a major heart deformity; the recipient died of bleeding complications six hours later. Kantrowitz went on to invent 20 life-saving heart-implant devices – including an intra-aortic balloon pump and an implant that assisted the left ventricle – which allowed patients to leave hospitaland live relatively normal lives. Healso pioneered a range of medical electronic devices and colour-motion pictures of surgery.

Kantrowitz might well have been the first heart transplanter: he had wanted to perform a transplant a year earlier but had been prevented because the donor infant had not been declared brain-dead. He was one of four pioneer heart surgeons, all American, who were researching transplant in dogs, and trying to overcome the rejection problems with the limited anti-rejection drugs then available. Of the others, Norman Shumway in Stanford went on to do the first series of heart transplants with long-term survival as well as the world's first heart-lung transplant. His colleague Richard Lower, who moved to Virginia, followed close behind; Michael DeBakey in Houston went on to make the first Dacron grafts and stents.

Adrian Kantrowitz was born in 1918 in New York, where his father was a general medical practitioner who charged patients 10 cents a week. His mother designed costumes for the Ziegfeld Follies. With his brother Arthur, who became a distinguished physicist, Adrian did kitchen-table research including making an electrocardiograph from old radio parts, and went on to take a maths degree at New York University, graduating in 1940.

The advent of war in Europe meant there was a shortage of doctors and he was accepted on to a fast-track medical course at the State University of New York, qualifying in 1943. He comp-leted an internship at Brooklyn Jewish Hospital, devising a clamp for use in brain surgery, which he intended as his career. Two years as a US Army doctor followed. When he was discharged, there were no training posts in brain surgery available, so he switched to the new speciality of heart surgery.

At Montefiore hospital in the Bronx he worked 18 hours a day, six days a week, for 15 years in the clinic and the laboratory. During this time he spent a two-year fellowship at the prestigious Western Reserve medical school in Cleveland, and in 1954 he co-invented a plastic heart valve that served as an additional pump. On 16 October 1951, he screened a film made inside a living dog's heart, which showed the mitral valve opening and closing, to 350 physicians at the New York Academy of Medicine.

In 1955 he moved to the State University of New York as professor of surgery, while concurrently being director of cardiovascular surgery at the Maimonides Hospital in Brooklyn. He stayed at SUNY for 15 years, devising gadgets that compensated for failing organs. These included, in 1958, an electronic heart-lung machine that enabled him to perform paediatric open-heart surgery. In 1959 he gave a healthy dog a booster heart muscle. He jointly invented a booster second heart that relieved the natural heart of 25 per cent of its work.

In 1960, he and a colleague built a device that delivered electric shocks to anaesthetised dogs' legs and produced walking movements; it later allowed paraplegics to move their legs. He also made a miniature radio transmitter with signals that allowed paralysed people's bladders to empty. He collaborated with General Electric to make an early heart pacemaker.

With a group of colleagues that included his brother, Kantrowitz built on existing artificial-heart technology during the 1960s. On 4 February 1966 he carried out the world's second implantation of an auxiliary heart; the patient died of liver disease 24 hours later. He repeated the operation, on 18 May 1966, on a 63-year-old, who had a fatal stroke a fortnight later. He and DeBakey, who was working on similar problems, decided the artificial heart was still a long way off.

His team's intra-aortic balloon pump fared better: a 1967 trial run proved successful and Kantrowitz used it from then on in heart-attack patients. It was a six-inch long, sausage-shaped device, inserted via the thigh, that deflated when the heart pumped blood and reinflated when it relaxed, reducing strain on the heart.

World-wide revulsion at unsuccess-ful heart transplants brought existing tensions to a head at Maimonides, and in 1970 Kantrowitz and his entire team of 25 with $3m of research grants, moved to Sinai Hospital in Detroit. There he stayed for more than three decades, and was concurrently surgery professor at Wayne State University medical school. He continued with balloon pump and mechanical auxiliary heart implants and transplantation experiments, despite a world-wide moratorium on human heart transplants. In 1971 he implanted an improved heart booster into 63-year-old Haskell Shanks, the first such patient to be sent home. He survived for three months.

In 1983 Kantrovitz and his wife founded L.VAD Technology, named after the left ventricular assist devices it manufactured; their latest device, which allows seriously ill patients to move around, is being assessed in clinical trials. He formally retired in 1993 but continued working for some years.

Caroline Richmond

Adrian Kantrowitz, heart surgeon: born New York 14 October 1918; Instructor in Surgery, New York Medical College 1952-55; Assistant Professor, then Associate Professor of Surgery, State University of New York Downstate Medical Centre 1955-64, Professor of Surgery 1964-70; Director of Cardiovascular Surgery, Maimonides Hospital 1955-64, Director of Surgical Services 1964-70; Chair, Department of Surgery, Sinai Hospital, Detroit 1970-75, Chair, Department of Cardiovascular Surgery 1975-83, Director of Surgical Research 1978-93; Professor of Surgery, Wayne State University School of Medicine 1970-93; married 1947 Jean Rosensaft (one son, two daughters); died Ann Arbor, Michigan 14 November 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments