The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

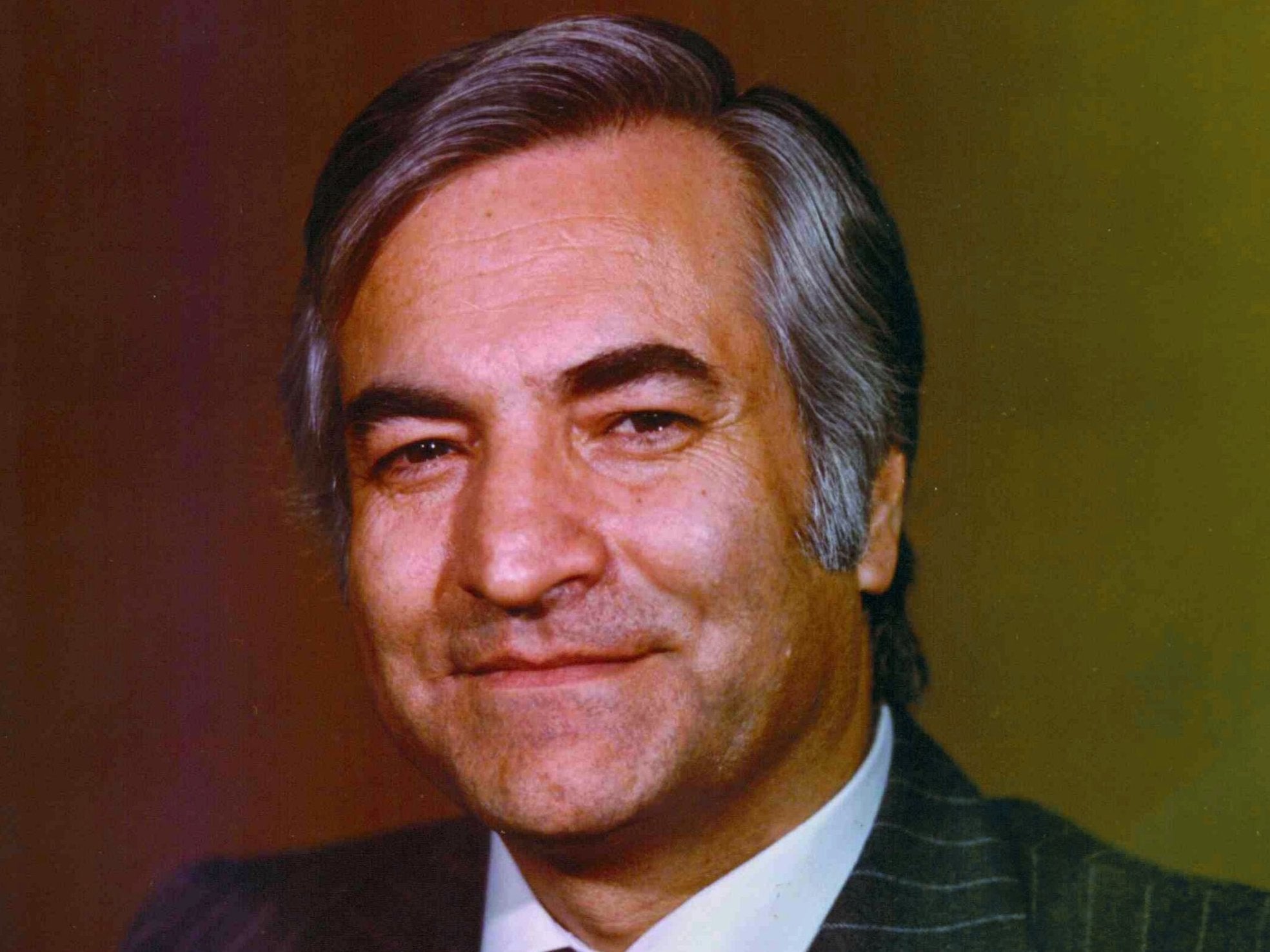

Abbas Amir-Entezam: Iranian politician who went from deputy prime minister to longest-suffering political prisoner

Despite enduring torture and solitary confinement at the hands of the Islamic Republic over 27 years, he refused offers of freedom without the chance to clear his name in court

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At once embodying both the great tragedies his nation had endured and the resistance it had showed in the face of them, Abbas Amir-Entezam is regarded by many as Iran’s Mandela – for he too spent 27 years in prison having refused conditional release.

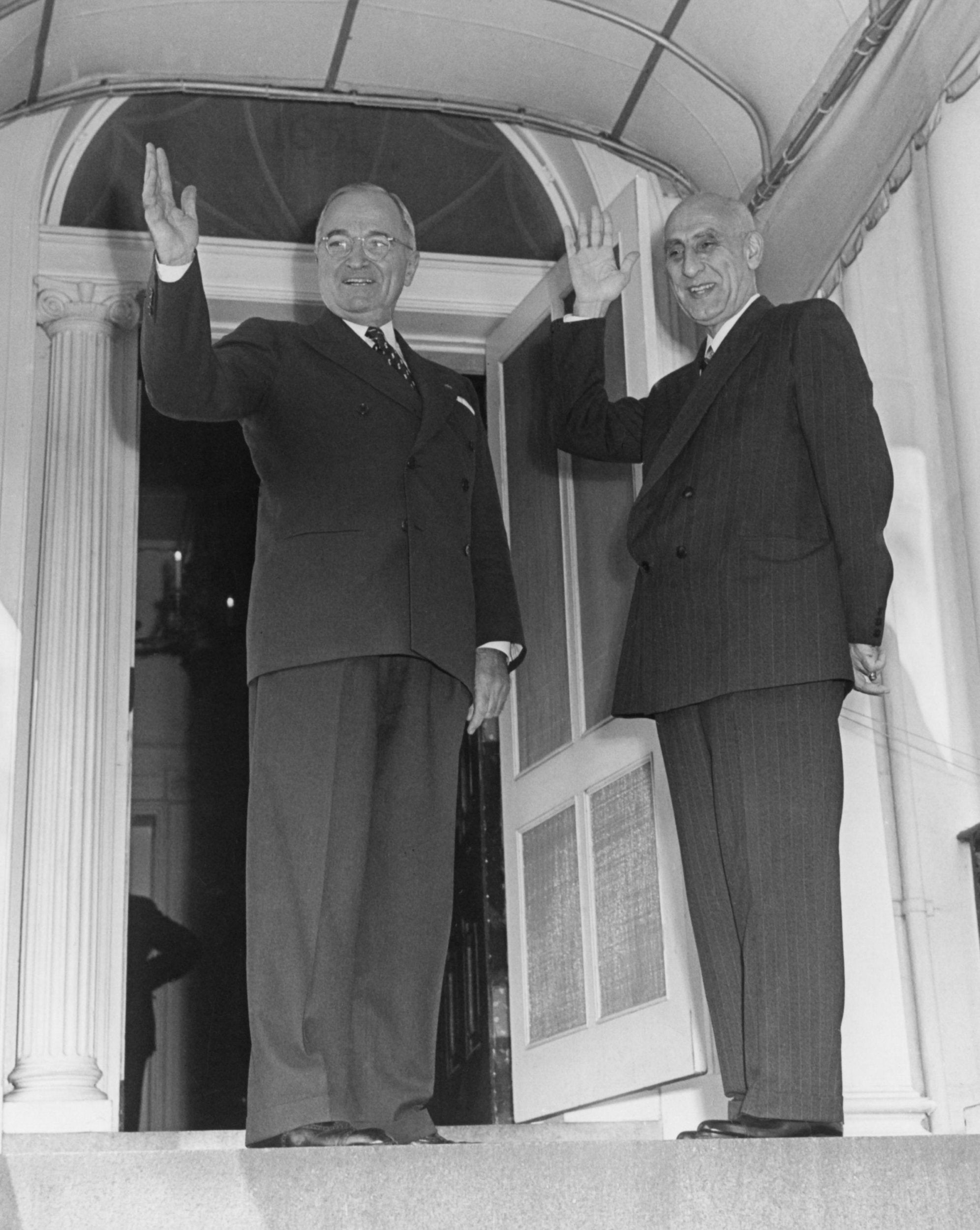

Born in 1932, Amir-Entezam came of age when Mohammad Mossadegh – the prime minister who stood against the British by nationalising Anglo-Iranian Oil Company – was inspiring an entire generation to dream of Iran free of foreign interference.

By 1953, having witnessed the fall of Mossadegh – who was ousted in coup chiefly backed by the CIA – Amir-Entezam had already become a dedicated patriot. He was one of the youngest stars of the National Front, the party of nationalists led by Mossadegh.

At 20, all the fearlessness and ambition of a leader in the making could be seen in Amir-Entezam. Convinced that the US was misinformed about his hero Mossadegh and his intentions, he walked into the American embassy in 1954, in the hope of establishing a direct line of communication between the US and the National Front.

The upshot of that daring act was a striking friendship with Richard Cottam, America’s only Persian-speaking diplomat – and, unbeknown to Amir-Entezam, an undercover CIA agent.

Through numerous dialogues, Amir-Entezam convinced Cottam that the US had, in fact, deeply misunderstood Mossadegh and had committed a grave mistake in helping organise the notorious 1953 coup against him (the CIA finally admitted its involvement in 2013).

In a series of cables and meetings with the State Department and the CIA, Cottam tried to convey these discoveries to the US administration. When Washington proved unreceptive, Cottam quit the agency to become one of the most respected scholars and outspoken critics of the US policy towards Iran before 1979.

Amir-Entezam’s next major encounter with America came in the 1960s when he was an engineering student at the University of California at Berkeley. There, he joined the ranks of the leading opposition figures against the Pahlavi monarchy.

In the 1970s, and upon the invitation of Mehdi Bazargan, Iran’s first post-1979 prime minister, he returned to Iran and the two began a business venture together. Businessmen by day and aspiring leaders by night, Bazargan and Amir-Entezam were a rare political duo on a socio-political scene which shunned financial success in an era of growing anti-capitalist sentiments.

After the victory of the 1979 revolution and the rise of its leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, to power, Mehdi Bazargan was named the first prime minister of the provisional government, and Amir-Entezam its first spokesperson. But the strange coalition of secular western-educated patriots dreaming of a democratic Iran and radical Shiites dreaming of a theocratic order could not last long.

Amir-Entezam’s most serious face-off with the clerical factions in post-revolutionary Iran came when, in drafting the new constitution, he objected to the notion of a “supreme leader”. In his view, placing a single individual above the law and endowing him with the power to override the constitution was against all democratic principles.

In July 1979, this conflict became so heated that prime minister Bazargan removed Amir-Entezam from his role of spokesperson and assigned him to Sweden as an ambassador. By sending his beloved protege out of the country, Bazargan had hoped the enmities Amir-Entezam had stirred would ease and be forgotten. But he had miscalculated the depth of those enmities.

By November of that year, when a group of university students seized the US embassy in Tehran, the radical clerical elements had found the perfect alibi with which to frame and eliminate all their foes. Dubbing the embassy a “nest of spies”, the students began to share documents they had captured at the embassy to spin their case against alleged spies within the ranks of Iran’s leadership.

In December in Stockholm, Amir-Entezam received an official communique summoning him back to Tehran for a confidential government matter. Several of his western counterparts, citing their own intelligence sources, beseeched him not to return. But Amir-Entezam, ever believing in the cause of the democracy he had hoped to usher in, did not listen – he returned.

Upon arriving in Tehran, Amir-Entezam was arrested and charged with spying for the United States. It was not the first time in history that a revolution was devouring its own. Only the revolution that devoured Amir-Entezam and imprisoned him for two decades before transferring him to house arrest was not able to vanquish him. He would not be erased.

A famous picture of him circulated among activists shows him chained to a hospital bed in prison.

From endless days in solitary and the harshest of tortures, he would return, unbroken, to lift the spirits of his younger prisoners and give them hope. After 10 years in captivity, he was offered a chance to leave prison by writing a letter, recanting his alleged sins of espionage and asking for a pardon – something hundreds before him had done. But Amir-Entezam refused. His nation had entrusted him with one of its highest offices, he argued with his tormentors time and time again, and he would not betray the people’s trust by admitting to the false charges.

Freedom meant nothing to him without the opportunity to clear his name. By refusing to leave prison, Amir-Entezam had done the unthinkable: he had turned the tables on his captors. In 1999, when Amnesty International began a campaign on his behalf, he had become the world’s best known and longest-held prisoner of conscience.

As international pressure to give justice to Amir-Entezam mounted and as his physical condition deteriorated, he was transferred to house arrest. There, Amir-Entezam was often visited by the new generation of opposition activists. He and his equally outspoken and politically uncompromising wife, Elahe Mizani – who also suffered imprisonment – became the beloved power couple of secular resistance in Iran. It was under house arrest that Amir-Entezam issued a call for a national referendum, the most widely held demand among Iranians today.

No doubt Iran, the birthplace of one of the world’s greatest civilizations, will someday shed the yoke of theocracy and fulfil the many hopes of its youths for a better future. In that Iran, the story of Abbas Amir-Entezam, his patriotism, his heroism, his service and his refusal to surrender to oppression, will be taught to school children as an icon of citizenship and sacrifice. Until then, his plight lives on in all those who fight for rule of law everywhere around the world.

Abbas Amir-Entezam, Iranian politician and prisoner of conscience, born 18 August 1932, died 12 July 2018

Roya Hakakian is the author of ‘Journey from the Land of No: A Girlhood Caught in Revolutionary Iran’ and ‘Assassins of the Turquoise Palace’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments