Review: Daphne Palasi Andreades on coming of age in NYC

Daphne Palasi Andreades’ debut novel is an emotionally-charged portrait of the defiance and desire imbued in young women growing up in New York City

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

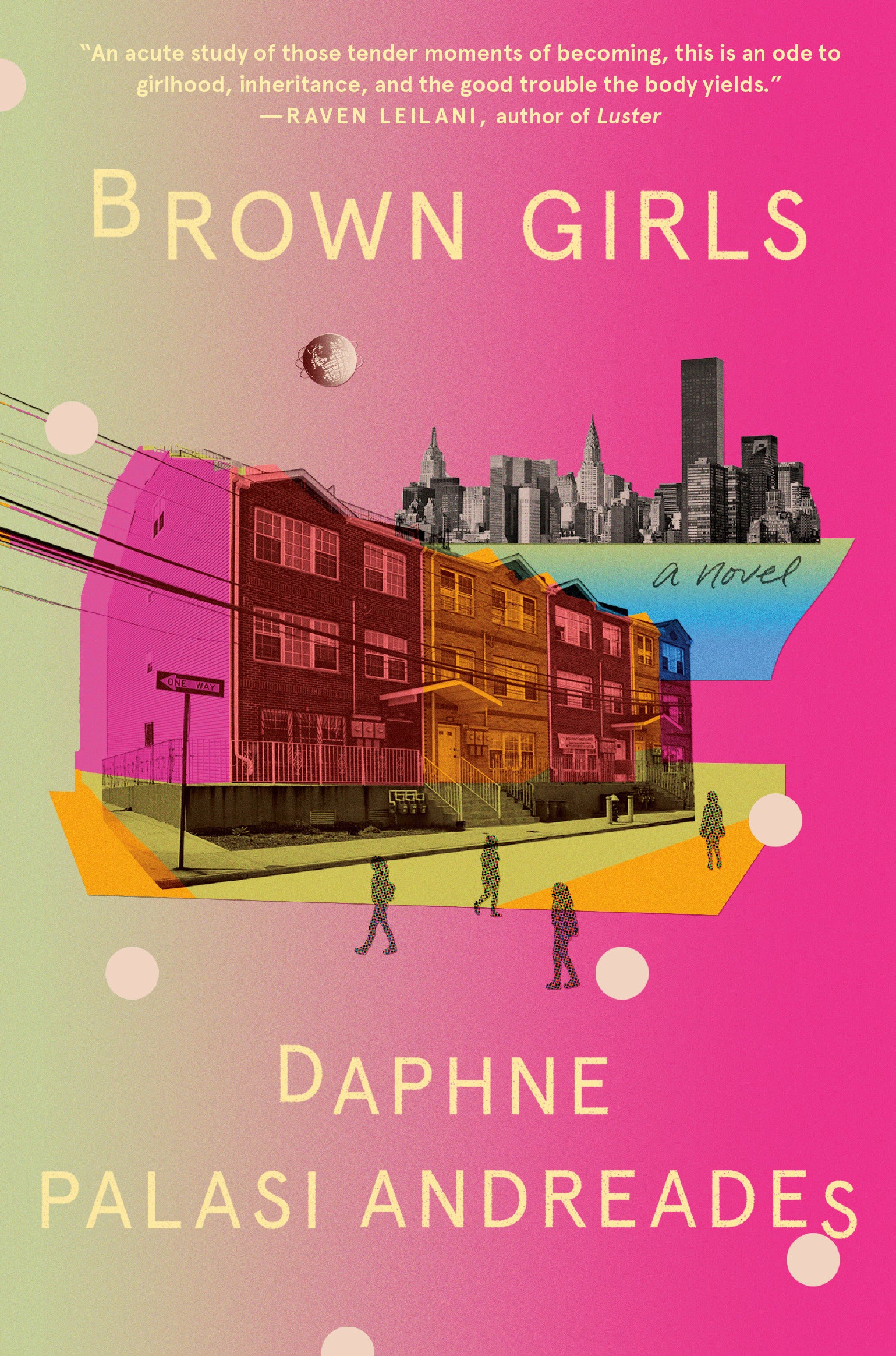

Your support makes all the difference.“Brown Girls” by Daphne Palacio Andreades (Penguin Random House)

Growing pains and heartache lead Daphne Palasi Andreades’ debut novel on the push and pull of becoming. Cast between stream of consciousness and coming-of-age, free verse and treatise, “Brown Girls” reckons with the periphery of the American dream — a state that may otherwise be known as girlhood.

Set in the Queens borough of New York City, the collective first-person narrator situates the anecdotal plot among the mutual upbringing of childhood friends. They are one and the same before their selfhood leads them on different paths, all allotted seven minutes in the morning for cold showers, all fed school cafeteria lunch also fed to prisoners, all sleeping at night in beds shared with siblings.

Gradually, adolescence awakens them to the limits their visibility poses upon their selfhood. Paranoid storekeepers break into the dressing rooms where they stand half-naked, classroom teachers mix them up for one another as they call them to the board, and parents threaten to send them back to their home countries after finding pillows instead of daughters under the sheets.

These moments are alive with the painful melancholy that takes the girls through their college years, when their boyfriends’ parents across town deem them the “grateful brown people,” as they question the values that alienate them in college, and as they visit the countries of their parents with hopes to find themselves.

Their divergent adulthoods are illuminated with questions between the girls who left Queens and those who didn’t, the girls who married and mothered and those who didn’t, and those who became professionals and those who didn't. The hypothetical power of these questions represent the essence of Andreades’ ruminative journey as an inscription into the negative space of being American, dark silhouettes surrounding a lighter established order.

Andreades’ work occupies the ephemeral circle of life that intertwines womanhood in class and race. Trading substance for style, “Brown Girls” displays an ambitious attempt to merge the sociological with the pictorial. Overwritten at times, and redundant in others, the novel is limited in scope by the characters who merit stronger development beyond stages of life positioned in the margins and their glossed-over international contexts. A fast pace that contains the entirety of their lives hinders the implications of the story.

“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” reads the text’s epigraph, a line of poet Emma Lazarus’ “The New Colossus” that is celebrated on the Statue of Liberty Had “Brown Girls” breathed deeper into that freedom, its significance would have resounded farther.