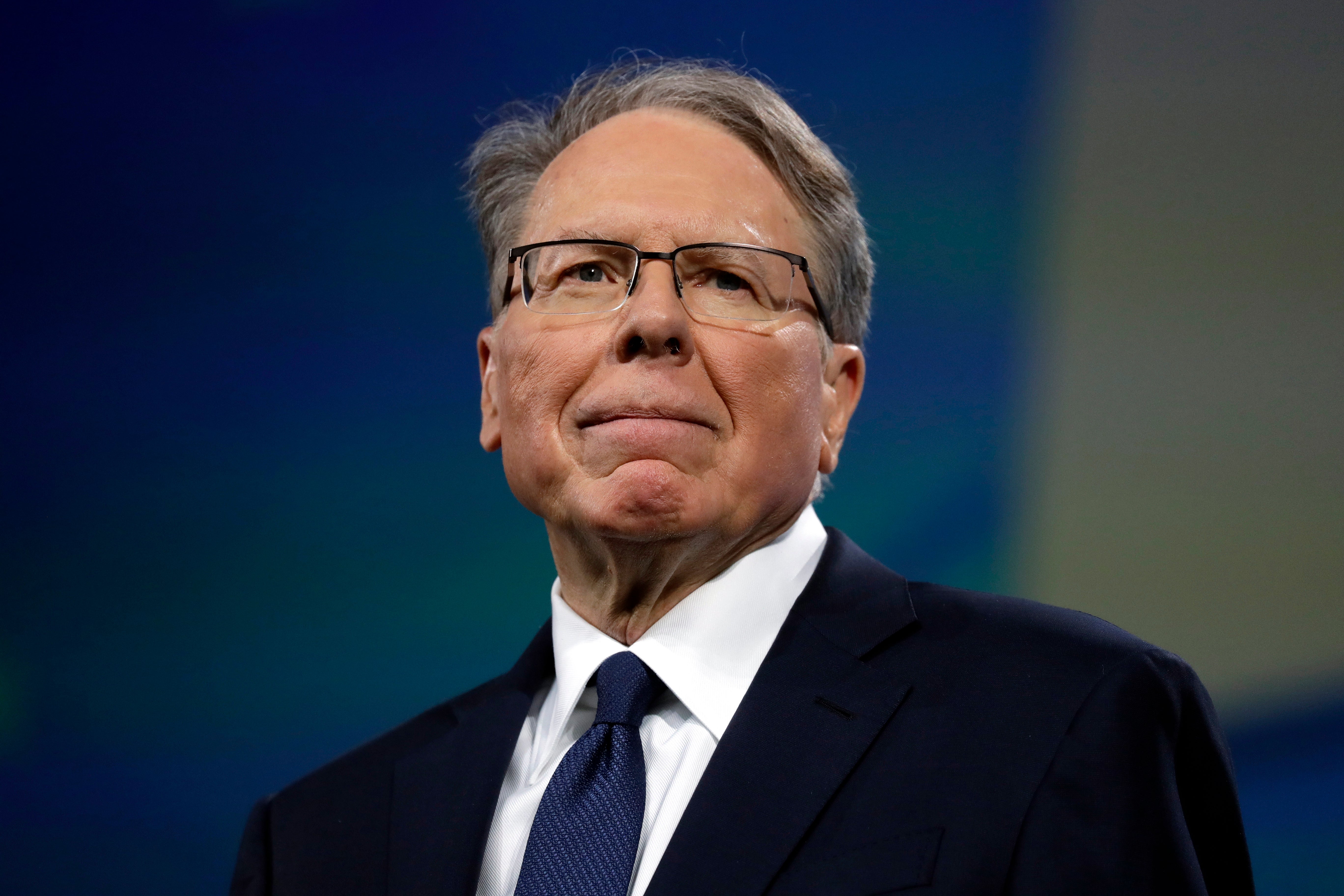

NRA trial opens window on secretive leader's life and work

Wayne LaPierre flies exclusively on private jets, he sailed around the Bahamas for “security” and never sends emails or texts in his work running the nation’s most politically influential gun-rights group

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Wayne LaPierre flies exclusively on private jets, he sailed around the Bahamas for “security” and he never sends emails or texts in the course of his work running the nation's most politically influential gun-rights group.

LaPierre's testimony this week during the National Rifle Association's high-stakes bankruptcy trial offered a rare window into the work and habits of the notoriously secretive titan of the American firearms movement.

Seldom seen in public outside choreographed speeches and TV appearances, the 71-year-old was blunt and occasionally combative under lawyers' questioning. He took the virtual witness stand in a federal case over whether the NRA should be allowed to incorporate in Texas instead of New York where the state is suing in a separate effort to disband the group over alleged financial abuses.

LaPierre’s testimony revealed him to be an embattled executive defending his leadership and punching back against what he characterized as a political attack by New York Attorney General Letitia James. But he also tried to acknowledge enough mistakes and course corrections to avoid having the NRA's reins handed to a court-appointed overseer — a move he said would be a death blow to the 150-year-old group that claims 5 million members.

The NRA declared bankruptcy in January, five months after James' office sued seeking its dissolution over allegations that executives illegally diverted tens of millions of dollars for lavish personal trips, no-show contracts and other questionable expenditures.

The NRA contends that its Chapter 11 filing is a legitimate maneuver to facilitate a move to a more gun-friendly state, Texas, and was made necessary by a Democratic politician who has “weaponized” her state's government. Lawyers for James' office, meanwhile, say it's an attempt by NRA leadership to escape accountability for using the group's coffers as their piggybank.

LaPierre appeared on camera before a court in Dallas on Wednesday and Thursday and was grilled by lawyers for New York and Ackerman McQueen, an Oklahoma City-based advertising agency that says the NRA owes it more than $1 million.

The questioning has focused on LaPierre's management of the NRA and the legitimacy of his filing for bankruptcy without first informing most of the group’s top executives and its board.

On Wednesday, a lawyer for New York asked why the state's investigation had turned up no emails or text messages from LaPierre.

“I'm old fashioned,” he replied. “I haven't sent any emails or texts.”

The allegations of financial abuses and mismanagement have roiled the NRA and threatened LaPierre’s grip on power. Political infighting spilled out in public during the NRA's 2019 annual meeting, where its then-president Oliver North was denied a second term. Tensions also eventually led to the departure of a man who'd been seen as LaPierre's likely successor, Chris Cox, who headed the group’s lobbying arm.

To be sure, it’s not unusual for chief executives of organizations the size of the NRA to travel by private plane or live lifestyles beyond the means of most people. But LaPierre’s alleged misspending of NRA membership dues came even as the group was urging supporters to donate so that it would have enough cash to battle gun control efforts.

Board members and former NRA leaders who support LaPierre didn't respond to requests for comment or referred questions to the NRA. Others who are skeptical of LaPierre’s leadership said the trial has only reaffirmed their concerns.

“I’m looking for the next Wayne,” said Phillip Journey, a board member and Kansas judge who is set to testify during the trial next week. “This can’t go on forever.”

LaPierre said Thursday that he kept the bankruptcy secret from the full board because he was worried that someone on it would leak the plan. “We were very concerned,” he testified.

He also said he was within his authority to file for bankruptcy with only the assent of the board’s three-member special litigation committee, he attacked James and New York's financial regulator as “corrupt,” and he repeatedly strayed beyond the bounds of yes or no questioning to defend his record.

LaPierre's efforts to explain his actions led to opposing lawyers moving to strike from the record much of what he said after nearly every question. He occasionally raised his voice and his expansive answers drew repeated warnings from his own attorneys and the judge.

“Can you answer the questions that are asked and do you understand that I’ve said that to you more than a dozen times in the last two days?” Judge Harlin Hale asked LaPierre on Thursday.

“I understand your honor," he replied. “I apologize if I’ve gone too long.”

LaPierre also, however, showed moments of regret and referred repeatedly to the NRA's “self-correction.”

For instance, he defended summer sailing in the Bahamas on a large yacht he borrowed from a Hollywood producer who has done business with the NRA. LaPierre said the family trips were a “security retreat,” noting that some came as he was facing threats months after mass shootings.

But he acknowledged that not mentioning the voyages on conflict-of-interest forms — which New York’s lawsuit contends violated NRA policy — was an oversight.

“I believe now that it should have been disclosed," he testified. “It’s one of the mistakes I’ve made.” ___

Associated Press writer Lisa Marie Pane in Boise, Idaho, contributed to this story.