Muslims are finding their place in America’s abortion debate

As the United States Supreme Court appears poised to overturn Roe v. Wade, Muslim Americans are gearing up for what the landmark reversal could mean for their communities

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.To Eman Abdelhadi, getting an abortion was the most sensible thing to do. She was six weeks pregnant and a graduate student who wasn’t financially ready to have a child. She felt no shame or guilt going through with it.

“I had no qualms about it. I grew up in an environment and a religious tradition that sees my life as the most important thing,” said Abdelhadi, a professor at the University of Chicago who was raised in a Muslim household. “It felt very clear to me. There was never anything like, ‘You did something unethical.‘”

___

This content is written and produced by Religion News Service and distributed by The Associated Press. RNS and AP partner on some religion news content. RNS is solely responsible for this story.

___

Abdelhadi, whose mother was a gynecologist in Egypt, grew up with the idea that abortion was a “nonsensical thing to legislate” and that legalizing it was necessary to prevent people from seeking other, potentially dangerous means of terminating pregnancies.

Islamic law is flexible, Abdelhadi said, and when it comes to making a decision about abortion, “people will consult with their families, their religious leaders, and then they’ll ultimately make a decision for themselves.”

“You’ll do what feels right,” she said.

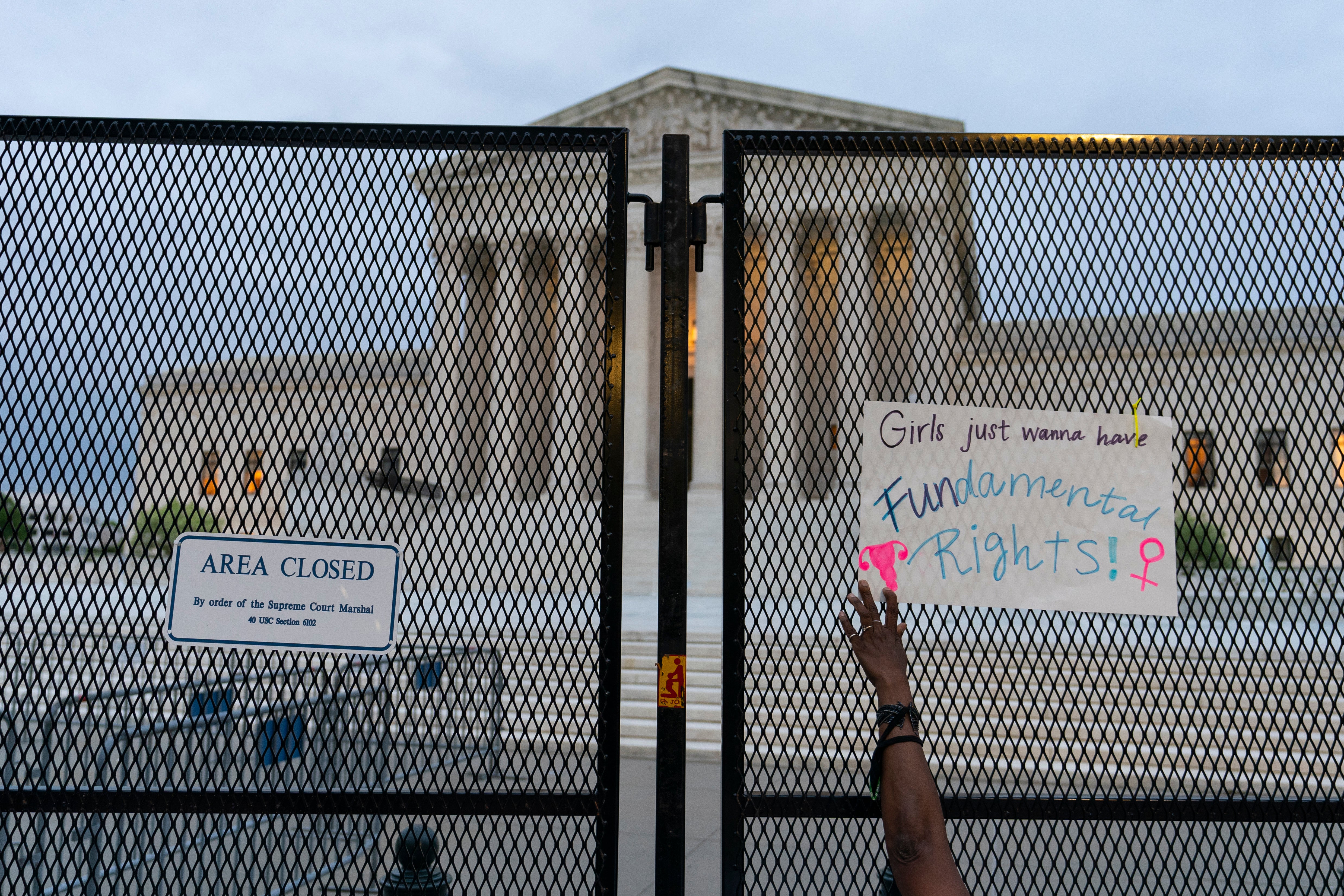

As the United States Supreme Court appears poised to overturn Roe v. Wade, Muslim Americans are gearing up for what the landmark reversal could mean for their communities.

HEART Women and Girls, a national reproductive justice organization serving Muslims, has formed a fund to provide financial assistance for pregnancy, abortion and miscarriage care. The LGBTQ Muslim group Queer Crescent is collecting abortion stories to learn how Muslims are accessing clinics, the costs and travel required, and the cultural barriers they overcome. And advocates and scholars are working to reclaim their Islamic history at a time when they say discussions around reproductive justice have often excluded or misrepresented Muslim voices.

“There’s been a sort of confused silence as (Muslim) folks try to figure out what they believe about this, or what Islam tells them about this,” said Abdelhadi, now a sociologist who studies Muslims in America. “I think what happens in a Christian-dominated space is that sometimes, even among Muslims, we don’t know what we believe.”

Recent passage of anti-abortion legislation in Texas and other red states has led many to make comparisons to the Taliban’s iron-fisted control of women in Muslim-majority Afghanistan. Such comparisons are inaccurate and perpetuate Islamophobia, experts say, adding that this rationale minimizes the role of Christianity and other U.S. systems that led to Texas’ six-week abortion ban.

The American Muslim Bar Association and HEART Women and Girls in April released an 11-page statement, dubbed “The Islamic Principle of Rahma: A Call for Reproductive Justice,” declaring that as a religious minority, Muslim Americans “are uniquely positioned to condemn abortion bans and their attack on every person’s constitutional right to religious liberty.”

“Muslims are not a monolith and we don’t have a systemized and global authority that mirrors the papal system in Catholicism. We also don’t hold a uniform view on when life begins,” the statement read.

Muslims have a rich understanding of conception, gestation, notions of life — and “abortion is part of that,” said Zahra Ayubi, a professor of religion at Dartmouth College and scholar of gender in premodern and modern Islamic ethics.

While Muslims have performed abortions since pre-modern times, Ayubi said contemporary concepts of when life begins are derived from Islamic legal tradition, pertaining to the inheritance rights of an unborn child or criminal laws addressing the fine a perpetrator would face for harming a pregnant person.

Cited are scriptural pieces from the Quran and the Prophet Muhammad that address developmental stages of a fetus and that give “descriptions of how creation came to be,” Ayubi said.

The discussion of when life begins varies from 40 days, the point at which the Prophet Muhammad says everyone is “constituted in the womb,” to 120 days, when the soul is believed to enter the fetus.

Among Muslim authorities, the most conservative opinion would say abortion is permitted as early as possible and only for health reasons before 120 days, Ayubi said. Contemporary Muslim jurists have universally said abortion is permissible even beyond 120 days “if there is mortal danger to the mother,” Ayubi added.

But even defining what constitutes mortal danger “is a nebulous kind of concept,” Ayubi said. This can include mental health concerns that, Ayubi said, “might lead to suicidal ideation.”

The Islamic tradition, Ayubi said, “is forgiving and on the side of mercy.”

In fact, Ayubi said, restrictive abortion laws in states such as Texas “take away from Muslim rights to abortion in their tradition and their religion.”

Abed Awad, a Rutgers adjunct law professor and national expert in Shariah (Islamic law), agrees.

If states outlaw abortion, Muslim Americans have standing to sue against abortion bans that interfere with their religious exercise, said Awad, adding that the issue of when life begins is a theological question.

The Texas law, currently one of the most restrictive abortion bans in the country, constitutes a religious violation of the First Amendment, said Awad, in that it subjects this “moral position of the Christian right and the anti-abortion movement” to other communities who don’t subscribe to these beliefs.

“This is not only contrary to the Shariah, but it’s also in a lot of respects contrary to living in a religious, cultural plural society,” Awad said. A Muslim pregnant woman in Texas, for example, wouldn’t be able to exercise her religion in Texas if she subscribed to the position of her medieval scholars who believed she was entitled to terminate her pregnancy before 120 days, Awad said.

In a webinar with Awad and other Islamic scholars, Ihsan Bagby — a professor of Islamic Studies at the University of Kentucky — said Muslims don’t need to be publicly behind either side of the abortion argument. Bagby characterized Awad’s position as a “liberal view of abortion.”

“The Islamic view is in the middle and we should stick to it. We don’t need to be cheering on the ‘women have a right to their body,’ as if it’s an absolute right, and we don’t need to be on the side of the ‘pro-life’ people because their intentions are ultimately to make abortions illegal across the board in all situations,” Bagby said.

Awad countered Bagby during the webinar, arguing the position to take is not as much around views on abortion but on defending a woman’s freedom to her own or her religion’s beliefs.

“What we’re fighting for is not that we support the liberal view of terminating a pregnancy within a particular time. We are fighting that women should have the right to decide which moral position they are going to take,” Awad argued during the webinar.

“I would not describe anything under Islamic law being something liberal or conservative,” he said.

Nadiah Mohajir, who co-founded HEART Women and Girls a decade ago to offer sexual and reproductive health programming to Muslims, said they’re proactively thinking of people who need “political education on why and how this ruling will impact Muslims.”

“The ways in which Muslims in America are talking about abortion, gender, sexuality, same-sex relationships, all of that is actually impacted by colonization and Christian supremacy,” Mohajir said.

While scholars say abortion in Islamic societies existed in pre-colonial times, Mohajir said most people wouldn’t know certain history and nuances unless they took a class specializing in it.

“Abortion was a matter between pregnant people and their providers and the state did not get involved, religious authority did not get involved,” Mohajir said. “lt’s important for us to reclaim that history.”

In partnership with HEART Women and Girls, Queer Crescent established the Muslim Repro Justice Storytelling project to combat “the taboo and the shame around thinking about abortion,” said Shenaaz Janmohamed, executive director of Queer Crescent.

They’re collecting written statements, audio clips and short videos from Muslims about their abortions. They aim to show that reproductive justice is “gender expansive” and not just a woman’s issue, and that when seeking abortion care, “Muslimness is part of what’s being interrogated as well as their ability to make decisions for their body,” Janmohamed said.

On top of launching its first reproductive justice fund, HEART Women and Girls is publishing its first book, called “Sex Talk: A Muslim’s Guide to Healthy Sex and Relationships,” which will cover how faith and cultural identities intersect with making decisions around reproductive health. It will highlight having “self-determination and agency over your body,” Mohajir said.

But to Mohajir, the scope of Islamic decision-making goes beyond just citing Islamic law. Mohajir points to Ayubi, the Islamic scholar who teaches at Dartmouth, whom she sees as working toward expanding “that conversation to include ethics and lived experience.”

“Considering those is just as important,” Mohajir said.

Ayubi, along other professors, is in the middle of collecting 500 interviews of religiously identified people who have had abortions. Described as the “largest data set” of its kind, it seeks to challenge “the narrative that religion is against abortion” and to understand how religious people think of “their abortions and their reproductive lives theologically.”

The Dartmouth professor is also working on an Islam and medical ethics project to document how Muslim women, as well as nonbinary and trans Muslims, go about making decisions related to abortion, gender-affirming therapies, pregnancy loss and in vitro fertilization.

In her callout for participants, Ayubi acknowledges that many have experienced anti-Muslim sentiment and racism from health care providers as well as their own family’s ideas of what medicines and procedures “we should have.”

“Many of us have made medical decisions that made us think about whether something is allowed in Islam,” Ayubi said.

The project is about “authority” and “autonomy” and it will “help other Muslims in similar situations,” she said.

To Mohajir, Islamic law has never been static. It has evolved with modern reproductive health technology such as IVF. Now, she said, there’s been a need for Islamic law to make an opinion of whether something like IVF is allowed or not.

“This is evidence to show that Islamic law evolves with time,” Mohajir said.

“Muslims are not a monolith. They not only are the most racially and ethnically diverse religious minority in North America, they’re also diverse even with respect to religious practice and lived experience,” she said.