Montana tribe gifts vaccines to neighbors across the border

A Native American tribe in northern Montana is giving unused COVID-19 vaccines to its First Nations relatives and others from neighboring communities in Canada

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On a cloudy spring day, hundreds lined up in their cars on the Canadian side of the border crossing that separates Alberta and Montana They had driven for hours and camped out in their vehicles in hopes of receiving the season’s hottest commodity — a COVID-19 vaccine — from a Native American tribe that was giving out its excess doses.

The Blackfeet tribe in northern Montana provided about 1,000 surplus vaccines last month to its First Nations relatives and others from across the border, in an illustration of the disparity in speed at which the United States and Canada are distributing doses. While more than 30% of adults in the U.S. are fully vaccinated, in Canada that figure is about 3%.

Among those who received the vaccine at the Piegan-Carway border crossing were Sherry Cross Child and Shane Little Bear, of Stand Off, about 30 miles (50 kilometers) north of the border.

They recited a prayer in the Blackfoot language before nurses began administering shots, with Chief Mountain — sacred to the Blackfoot people — rising in the distance. The prayer was dedicated to people seeking refuge from the virus, Cross Child said.

Cross Child and her husband have family and friends in Montana but have not been able to visit them since the border closed last spring to all but essential travel.

“It’s been stressful because we had some deaths in the family, and they couldn’t come,” she said. “Just for the support – they rely on us, and we rely on them. It’s been tough.”

More than 95% of the Blackfeet reservation's roughly 10,000 residents who are eligible for the vaccine are fully immunized, after the state prioritized Native American communities — among the most vulnerable U.S. populations — in the early stages of its vaccination campaign.

The tribe received vaccine allotments both from the Montana health department and the federal Indian Health Service, leaving some doses unused. With an expiration date fast approaching, it turned to other nations in the Blackfoot Confederacy, which includes the Blackfeet and three tribes in southern Alberta that share a language and culture.

“The idea was to get to our brothers and sisters that live in Canada,” said Robert DesRosier, emergency services manager for the Blackfeet tribe. “And then the question came up – what if a nontribal member wants a vaccine? Well, this is about saving lives. We’re not going to turn anybody away.”

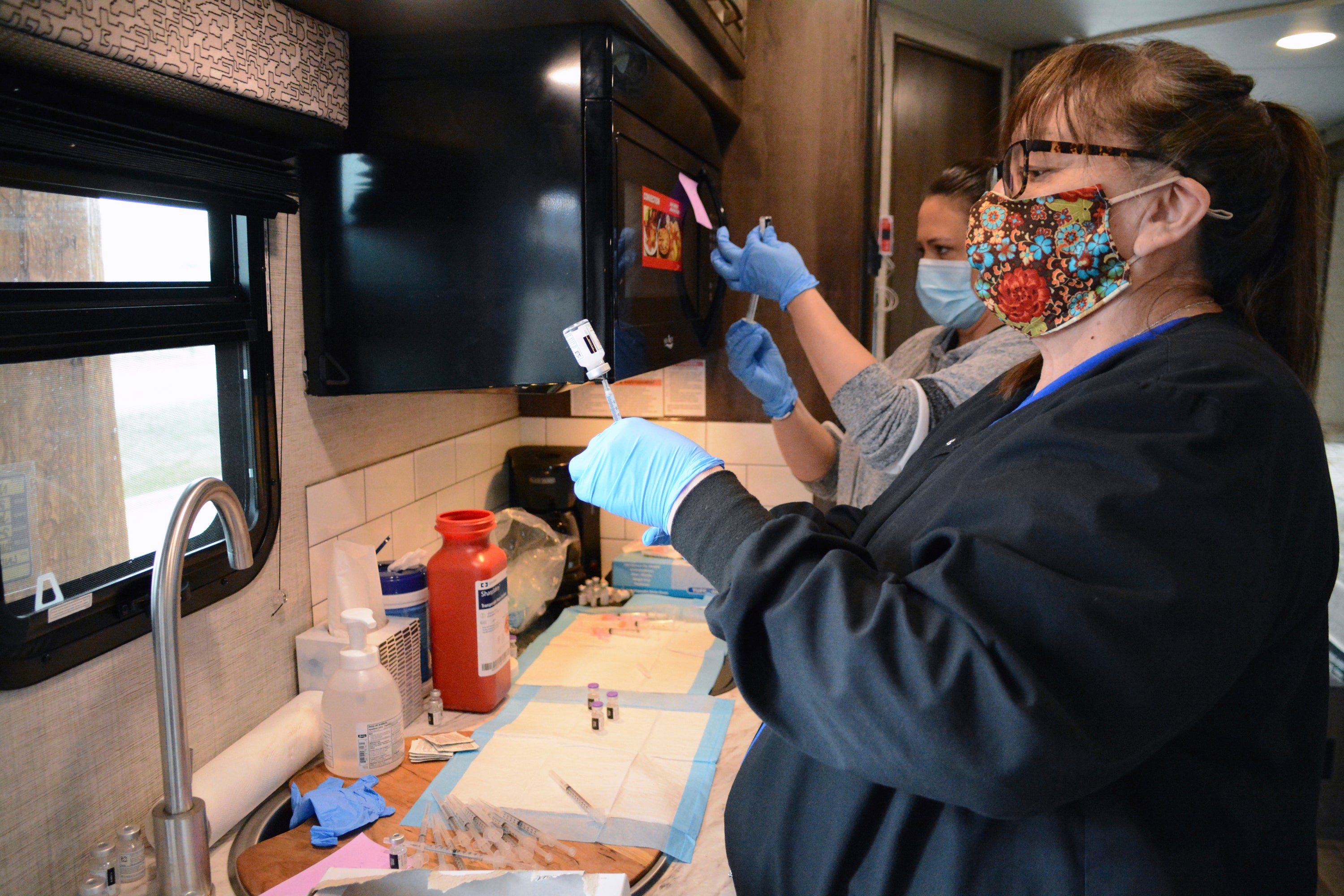

The tribe distributed the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines over four days in late April at the remote Piegan Port of Entry, amid a backdrop of rolling grasslands to the east and Glacier National Park's snow-covered peaks to the west.

As news of the effort spread in Canada, first by word of mouth, then through social platforms and media reports, people traveled from farther away. Some drove five hours from the city of Edmonton.

The effort was particularly timely as Alberta sees a surge in new cases of the respiratory virus, with a caseload record reached this month.

Bonnie Healy, Blackfoot Confederacy health administrator, said she was glad the vaccination effort reached both First Nations and other communities in the province.

“We have family members that live in those areas,” she said. “If we can get these places safe, then it’s safe for our children to go to school there. It’s safe for our elders to go shopping in their stores.”

Canadians who got the vaccines were not allowed to linger in the U.S. They returned home with letters from health officials exempting them from the mandatory 14-day quarantine imposed on all those entering the country.

The tribe’s initiative is one of a few partnerships that have cropped up between communities in the U.S. and Canada, where residents might otherwise have to wait weeks or months for a shot. Canada has lagged in vaccinating its population because it lacks the ability to manufacture the vaccine and has had to rely on the global supply chain for the lifesaving shots, like many other countries.

In Alaska, Gov. Mike Dunleavy has offered COVID-19 vaccines to residents of Stewart, British Columbia, with hopes it could lead the Canadian government to ease restrictions between that town and the Alaska border community of Hyder, a couple of miles away. In North Dakota, Gov. Doug Burgum and Manitoba Premier Brian Pallister unveiled a plan last month to administer vaccinations to Manitoba-based truck drivers transporting goods to and from the U.S.

On the Montana side of the border, vaccine recipients were often emotional, shedding tears, shouting words of gratitude through car windows as they drove away, and handing the nurses gifts such as chocolate and clothing. Some shared stories about what the vaccine meant to them – the possibility of safely caring for vulnerable loved ones, reuniting with grandparents or traveling again.

Recipients included 17-year-olds who are low on the country’s priority list and parents who camped out with their young children in the backseat.

Maxwell Stein, 25, who plays the horn with the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra, arrived at the border crossing at 6 p.m. Wednesday and spent the night in his car, finally reaching the front of the line around 10 a.m. Thursday.

“It wasn’t awesome, but you do what you need to to get a vaccine,” he said. He predicted that if he had waited in Canada, he’d likely get his first dose sometime in late June, and it would be months before he would be fully vaccinated.

The Canadian government has recommended extending the interval between the two doses of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines from around three weeks to four months, with the goal of quickly inoculating more people amid the shortage. Some who attended the Blackfeet clinics had already gotten their first shot in Canada. More than 30% of Canada’s population has received at least one dose of the vaccine, but around 3% have received both doses recommended by the drug manufacturers to reach full immunity. Canadian officials say partial immunity is better than none.

“It’s unfortunate because one shot only protects you slightly,” Stein said. “With vaccines, I think it’s really important to get the correct dosage in the right time period, so your body builds up the full resistance.”

When Stein heard about the vaccine clinic on the border, he didn’t hesitate about the long drive, particularly as a professional musician who has a lot of free time with many concerts canceled.

“Really, I have no excuse. If I had to drive 10 hours to get the Pfizer or Moderna, I probably would have done it,” he said.

___

Samuels is a corps member for The Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.