DA: Investigators blew chances in case of Durst wife's death

A prosecutor in suburban New York says authorities decades ago blew chances to build a case against multimillionaire Robert Durst in the death of his first wife

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Authorities decades ago blew chances to build a case against multimillionaire Robert Durst in the death of his first wife, a suburban New York prosecutor said Wednesday after Durst's death last week in a California hospital lockup quashed a case that took nearly 40 years to bring.

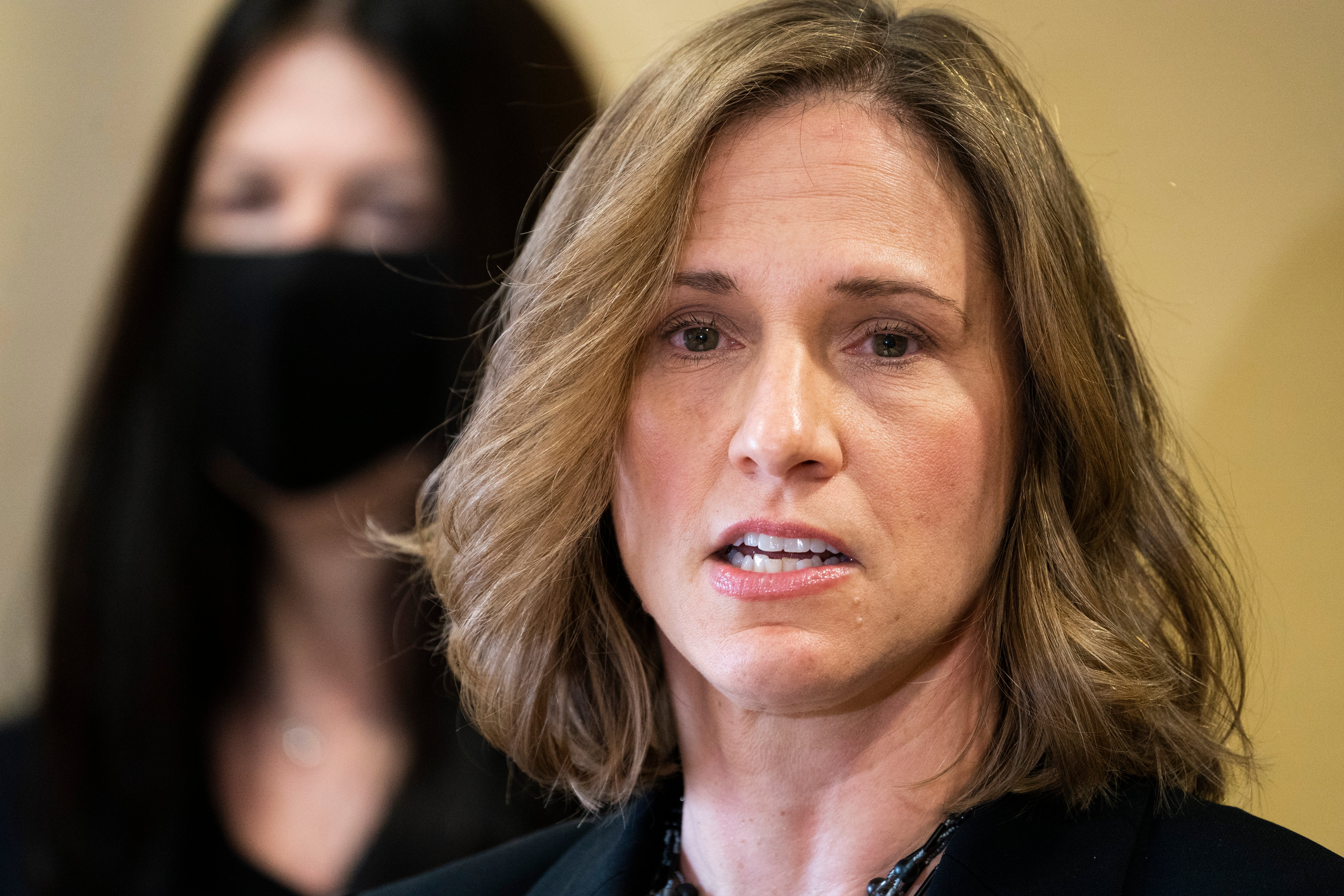

Westchester District Attorney Mimi Rocah cited “tunnel vision” — and underscored that she wasn't “putting blame anywhere” — for investigative shortcomings she recapped in a report on her office's recent re-investigation of the 1982 disappearance of Kathie McCormack Durst. The renewed probe led to a murder indictment this past fall against her incarcerated former husband.

Rocah said at a news conference that her inquiry had turned up some new witnesses and physical evidence that corroborated elements of the case, and that her office had re-interviewed some witnesses who were “more forthcoming than before,” but she didn't elaborate.

Noting that grand jury secrecy laws prevent divulging some of what investigators learned, the report essentially recaps facts that already had emerged publicly.

“Some missed opportunities by law enforcement officials directing the early stages of the investigation may have contributed to delays in bringing the charges in this case,” Rocah said.

Authorities now “can and must learn from this," she said, particularly for future investigations involving rich, powerful and high-profile people.

An attorney for Kathie Durst's family blasted the DA's remarks as an attempt “to explain away how money, power, and influence allowed a killer to escape justice” and called on Rocah to resign.

“We ask the public to consider why the current Westchester DA and her predecessors remain unwilling to tell the truth about why it took nearly forty years for Robert Durst to be charged,” the lawyer, Robert Abrams, said in a statement.

Durst has always maintained that he last saw his then-wife when he dropped her off in Westchester County for a train to New York City, where they had an apartment and she was in medical school.

Investigators initially let themselves be “guided by Durst’s version of events” despite inconsistencies, Rocah said.

For example, although Durst said the two weren't having marital problems, one of their Manhattan neighbors told police that his wife had said he had beaten her and repeatedly sought shelter from him in the neighbor's apartment, once climbing over via their adjacent balconies.

Meanwhile, neighbors he said he had visited in Westchester after dropping her at the train denied that he came over, and a cleaner at the Dursts' weekend home noticed some unusual things — including what she believed was blood on the dishwasher — and said he had told her to dispose of many of his wife's possessions shortly after she vanished.

But police didn't thoroughly search the Westchester home. The investigation remained focused in Manhattan, where a few witnesses reported they had seen Kathie Durst on the night of her disappearance and the dean at her medical school said he had gotten a phone call from her the next day.

A re-investigation that the New York State Police and the DA's office began in 1999 frayed both those threads of evidence. The witnesses said they were mistaken or uncertain, and evidence developed that the medical school caller who said she was Kathie Durst was actually Susan Berman a writer who was Robert Durst's best friend.

Berman was found slain in her home in her Los Angeles in December 2000, before a state police investigator could follow through on plans to interview her.

Durst was convicted in September of killing her, with prosecutors arguing he did so to keep her from incriminating him. Rocah said the Los Angeles case paved the legal way for the New York charges.

Kathie Durst was declared legally dead in 2017, but her body has never been found.