As tanks rolled in 1991, AP photographer sprang into action

On Aug. 19, 1991, a group of top Communist Party hard-liners declared they had removed Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev from power and declared a state of emergency in the country

On the morning of Aug. 19, 1991, I woke up to a loud rumbling outside. It was the same sound I heard during an earlier showdown between Soviet troops and pro-democracy protesters in Lithuania.

It was the sound of battle tanks.

The ominous noise on that morning 30 years ago was coming from the main state TV headquarters, a 15-minute walk from my apartment building in northern Moscow When I went outside, I saw troops encircling state broadcast facilities and the massive Ostankino TV tower.

The hundreds of tanks rolled into Moscow after a terse statement was broadcast declaring that Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev who was on vacation at the Black Sea, was unfit to govern for health reasons. A group of hard-line Communist Party officials formed what they called the “State Committee on the State of Emergency” to save the country from “chaos and anarchy.”

___

EDITOR'S NOTE: Associated Press photographer Alexander Zemlianichenko rushed into the streets of Moscow on the morning of Aug. 19, 1991, after a group of hard-line Communist Party officials seized power in a coup. The images of demonstrators standing up to the tanks and troops that Zemlianichenko and his AP colleagues made during the tumult and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union won the 1992 Pulitzer Prize for Spot News Photography.

___

That day, my wife and I were supposed to start our vacation in Cyprus — a long-coveted trip that was our first chance to visit the Mediterranean. Instead, I packed my gear and headed to The Associated Press office, located across the river from the government headquarters of the Russian Federation, one of 15 Soviet republics, which was headed by Boris Yeltsin

Yeltsin was widely seen as the champion of democratic reforms, defying those hard-liners who were trying to preserve Communist Party rule. His offices in a towering riverside building, dubbed the “White House” by Muscovites, served as a rallying point for those who opposed the coup.

When I reached the building, crowds were swarming the tanks sent to surround the building. Some of the tank crews got out of their vehicles and declared that they would side with protesters.

Yeltsin arrived and climbed atop one of the tanks to make a passionate speech, urging people to stand up against the coup plotters.

I spent that chaotic day taking photos of protesters around Yeltsin's headquarters and running back the office to have my rolls of film developed.

Later in the day, the leaders of the coup defended their actions at a televised news conference, but they appeared nervous and indecisive. As state TV showed Yeltsin defying them, it became increasingly clear that their plot was doomed.

Tensions remained high, however, and three protesters were killed and several others were injured when a crowd tried to stop a convoy of armored vehicles that they believed was heading to storm Yeltsin's headquarters.

Hours later, on the morning of Aug. 21, Soviet Defense Minister Dmitry Yazov ordered troops to leave Moscow. The next day, Gorbachev flew back to Moscow, and the coup plotters were arrested. One died of a gunshot wound in an apparent suicide.

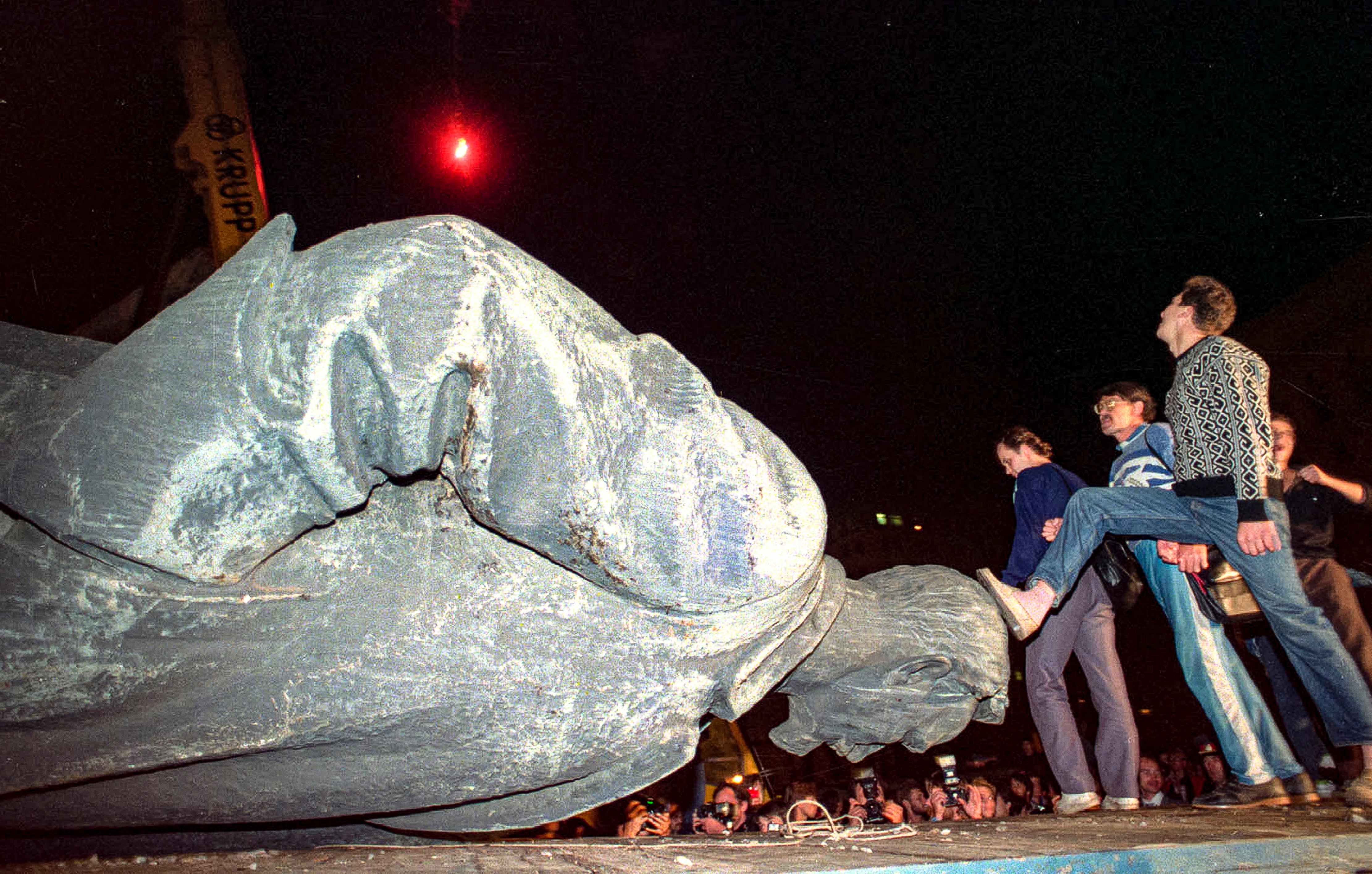

I was still out on the streets, taking photos of exultant crowds across the city. I caught the moment when demonstrators pulled down a large statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky, the founder of the Soviet secret police, in front of KGB headquarters on Lubyanka Square.

It was a watershed moment that symbolized the collapse of the repressive Soviet system.

The botched putsch dramatically weakened Gorbachev, making Yeltsin the No. 1 political figure and hastening the collapse of the Soviet Union four months later.