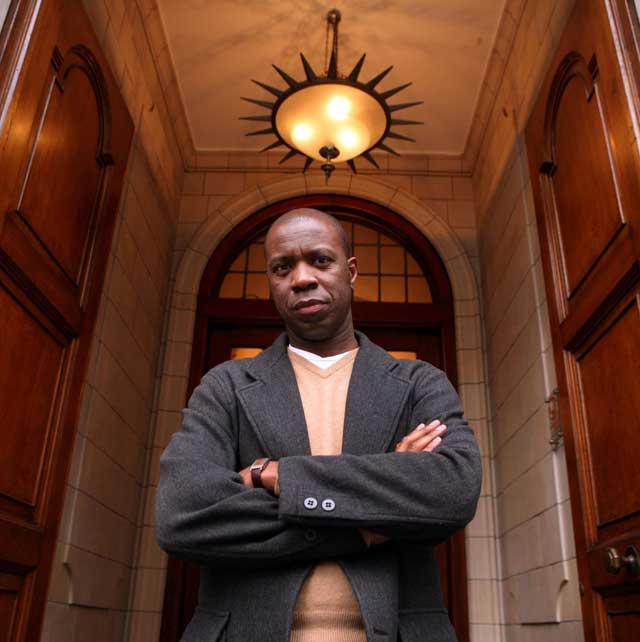

Clive Myrie: The man who took over Sir Trevor McDonald's mantle

Clive Myrie has replaced his hero as Britain's most prominent black broadcast journalist. He tells Ian Burrell what motivates him

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Bolton, the early Seventies. A Jamaican mother is doing her work as a seamstress, her husband is home from the factory where he makes car batteries, and their young son sits in front of the television watching a bulletin from ITN, transfixed. On the screen, a Trinidadian reporter newly recruited from the BBC World Service, is speaking to camera.

Clive Myrie still holds his childhood memories of Sir Trevor McDonald, even now that the BBC Europe correspondent is himself Britain's most prominent black broadcast journalist, fittingly chosen to present the corporation's landmark documentary Obama: His Story, shown on BBC One last week and on BBC Two on inauguration day.

"Trevor McDonald was the only guy on screen that looked like I did. One week he'd be in one country, the next week in another. He seemed to be having a really good time, really enjoying it," says Myrie. "I thought, from a very young age – seven, eight – that was what I wanted to do. I wanted to travel and see the world and experience life."

Myrie, 44, is very much the hard-nosed reporter, a veteran of the hottest hotspots of the last two decades; Kosovo, Palestine, Afghanistan. Most memorably, he was alongside 40 Commando when that Royal Marines unit entered Basra under heavy fire during the early days of the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Narrating the advance on camera as gunfire from Saddam's soldiers crackled around him.

But the Obama documentary has raised his profile to a new level. Myrie, though he has been based in Brussels since 2007, formerly worked out of Washington and Los Angeles and was desperate to play a key role in the election story, firing off story ideas to bulletin editors in London.

The documentary demonstrated the depth of Myrie's experience as an American correspondent, as he secured interviews with the likes of Alice Walker and Jesse Jackson. "I wouldn't call him a bosom buddie but I've interviewed him several times, and there's a rapport that's already there," he says.

Myrie travelled to Hawaii to speak to those who knew "Barry" Obama in his schooldays, digging out footage showing the President as a proficient young basketball player, an American sports commentator enthusing "Breakaway...Obama...left-handed" as Barry gracefully lays up a basket.

And on election night, Myrie was part of the BBC team, stationed at Morehouse College, Atlanta, the alma mater of Martin Luther King. "It was incredibly emotional for me, as a black man, to see a black man put in the most powerful position on earth," he says.

So emotional in fact that he slightly lost composure as he commentated over pictures of black students in tears before handing back to David Dimbleby in London. "At the end of it, I said 'I have to tell you, it's a privilege for me to be here at this particular moment in time,' and as soon as I said that I thought 'Damn, I've crossed the line. This is the BBC and I've become too emotional'." Myrie felt a little better when he turned around to see the black ABC News reporter Steve Osunsami openly crying as he addressed his viewers live on air.

The civil rights story has moved so fast from the days when Myrie was based in America and "went down to Mississippi and interviewed a man who had survived a lynching," he says. "To be covering that sort of story one minute and reporting Rosa Parks's funeral, and reporting from Mississippi on former Ku Klux Klan members being brought to justice, and then be in Morehouse College that day was incredible."

He recently had the chance to tell Sir Trevor "he was a bit of a hero of mine" when both participated in a seminar to try to encourage more ethnic minority students to enter broadcast journalism. He regrets that others of his background have not followed a similar career path to his own. "You've only got to look at the TV screens to see there's not the kind of representation of black Britons on the screen as one would like," he says, expressing the view that the BBC has worked hard to rectify this but is hampered by an enduring notion that it is a bastion of a white elite.

As a young man, Myrie held similar fears, in spite of his strong sense of vocation, and after a law degree at Sussex University expected to work in independent radio. He was surprised to land a BBC traineeship and has been at the corporation nearly his entire career.

It's not been without difficulties. As Asia Correspondent in Tokyo his attempts to interview a senior businessman were hampered by his subject's determination to speak only with Myrie's white American producer. "He wouldn't look at me, even though he was told I was the correspondent, he was convinced I was the bag carrier. In the end I had to say 'Excuse me, I'm going to be conducting the interview'."

In America he has had to break through the notion that black Britons don't exist. "When I was working in Los Angeles one guy was convinced I was putting on my accent, he was convinced I was making it up," he complains in his rich vowels. "And they all think I'm incredibly posh. Well, I'm from Bolton!"

Though he lives in Belgium, Myrie can go to a breaking story anywhere in the world at short notice. That usually means somewhere dangerous. In Iraq he was embedded with the marines, as much as the Rolling Stone reporter Evan Wright, who turned his experience with US soldiers into a book and subsequent TV series Generation Kill. "I have a hell of a lot of respect for the marines and the job that they do, in a way that I may not have had before the whole thing started," says Myrie, who admits to controversially having handed flares to a marine he was embedded with during a frantic attack on an Iraqi bridge. "I'm not entirely sure what else you do in that sort of situation," he says. "For me that was not the moment to draw the line and make it clear you are a journalist. It didn't feel like the right thing to do, just from being a human being frankly."

He is confident in his moral compass and his ability to communicate from the frontline. "I have found over the years that I have a capacity to tell a compelling story in a conflict situation," he says. And while he acknowledges his wife's fears for his safety, it is the desire to relate such tales that makes Myrie tick. "She knows that's part of my make up. If I didn't cover some of these stories I wouldn't be as sanguine and happy as I am, shall we say."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments