Charlie Hebdo attack: The battle between political cartoonists and the forces of censorship has been going on for centuries

John Walsh traces the rich history of political satire and its power to provoke extreme reactions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Historians of visual satire and its suppression by the forces of darkness must have experienced feelings of déjà vu about the infamous events in Paris on Wednesday.

They might recall another satirical weekly magazine, published in the French capital, devoted to blackly humorous criticism of politics, religion and current affairs, employing some of the best writers and artists of its day, which was attacked by furious supporters of its targets, determined to put it out of business.

But it's not Charlie Hebdo – it's La Caricature, Morale, Politique et Litteraire, which flourished in the 1830s in the reign of Louis-Philippe.

La Caricature ran to just four pages with two lithographs, but it wound up the authorities to breaking point. It attacked the incompetence of the government and the complacency of the king with increasing savagery. Writers of the calibre of Balzac were among its contributors. Honoré Daumier, the distinguished painter and sculptor, contributed lithographs. It says a lot for the French spirit of the age, nearly 200 years ago, that a satirical comic could attract such people. And it says a lot for the sensibilities of the affronted that it couldn't last.

When Daumier published a caricature of Louis-Philippe as Gargantua, the gross, all-consuming giant from Rabelais's novel, Gargantua and Pantagruel, he was imprisoned for six months. When the magazine's director, Charles Philpon, ran a cartoon showing the king as a fat-bottomed pear – an image that appeared on walls all over Paris – he was imprisoned for a year. The government finally passed legislation that closed down La Caricature.

Philpon bounced back with Le Charivari, and history obligingly repeated itself. Daumier published a horrifying picture of a massacre during the Paris riots of 1834 and circulated it to promote freedom of the press and raise money for Le Charivari. The police moved in, tracked down as many prints as they could find and destroyed the lithographic stone on which they had been made.

William Thackeray, author of Vanity Fair, looked at this crushing of the press and, in 1840, puzzled over the "curious contest between the State and M Philpon's little army... Half-a-dozen poor artists on the one side, and his Majesty Louis-Philippe, his august family, and the numberless placemen and supporters of his monarchy, on the other."

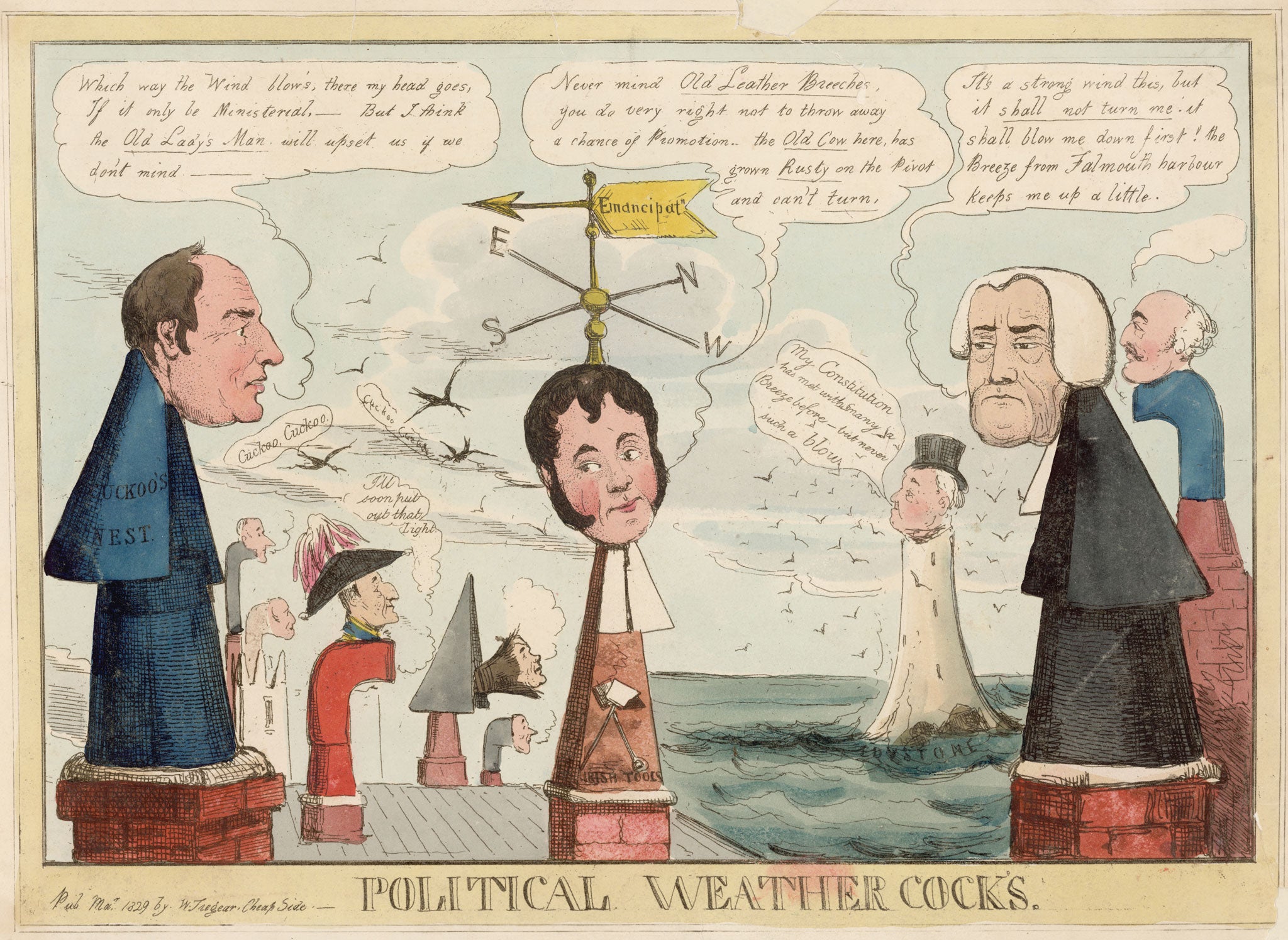

Nut, let me introduce sledgehammer. But satirical images of the powerful didn't start in France. They were a very English phenomenon. Art-historical orthodoxy suggests that they were born in the late 18th century by the happy confluence of a mad king, George III, a heady political climate of Whigs versus Tories, a newly gossipy social register fuelled by the rise of coffee houses, pamphlets and newspapers, and a salutary lesson – coming from both France and America – about the vulnerability of monarchies.

Four satirical geniuses appeared in this febrile period. William Hogarth borrowed Italian ideas of facial caricature to suggest moral or immoral character in human faces. James Gillray mercilessly mocked the art world, gamblers, lechers and the dullness and austerity of the royal court. He was especially rude about the Prince of Wales's drinking and profligate spending. His royal victims had no recourse except to buy up so many of the prints that they wouldn't reach a wide audience. For a time, Gillray was the Tories' lampooner-in-chief, paid £200 a year to ridicule the Whigs; but after the fall of William Pitt's government, he attacked both parties with glee. His masterpiece is The Plum Pudding in Danger, showing Pitt and Napoleon carving up the globe between them; Napoleon with mad intensity, Pitt with icy precision.

Thomas Rowlandson was an exact contemporary of Gillray but lacked his fiery indignation. He was a portly, genial hedonist who preferred to portray gluttons, strumpets, pinched vicars, hoggish squires and fat John Bull. He liked showing what politics could make people do: like The Devonshire, or Most Approved Method of Securing Votes, in which the famous political salonniere, the Duchess of Devonshire, is shown about to snog a butcher to make sure he votes for Charles James Fox.

George Cruickshank grew up during the Napoleonic wars and constantly laid into the French emperor, but he also delighted in portraying the Prince of Wales as a bloated, leering, complacent slug or sea-monster: his The Prince of Whales or The Fisherman at Anchor is especially savage. When the prince became King George IV, he went so far as to bribe Cruickshank not to portray him "in any immoral situation", and the artist obediently turned his pen to other areas, such as book illustration (especially Dickens's novels.)

This golden age of caricature ended in the 1830s, as illustrated magazines and newspapers took over, and Victorian moral codes put an end to the vulgarity and fat-monarch jokes. The focus shifted to France, as we have seen, and the comic pamphlets, Caricature and Charivari. But after Louis-Philippe banned political cartoons altogether, their best exponents followed their English counterparts into book illustration.

After a 130-year hiatus, savagery returned with the British satire boom of the 1960s, and the rise of Ralph Steadman and Gerald Scarfe. The latter quickly established himself as possessed of a Swiftian, excremental vision, wholly unbothered by qualms of taste. His Sunday Times columns always pushed the envelope: he portrayed Harold Wilson about to lick Lyndon Johnson's bottom (Special Relationship) and Margaret Thatcher as a dog at Crufts on a plinth surrounded by turds (Top Bitch). His targets were always political, but although he was often criticised, nobody sought to stifle him.

The Iranian fatwa on The Satanic Verses in 1989 was the first sighting-shot of a new war, between hard-line Islamists and the blithe libertarianism of Western culture, which felt it could publish what it liked and mock whatever it wished. The fatwa, from the fundamentalist heirs to the Westernised Shah, showed that ancient objections to blasphemy could still be invoked. "We are not interested in your excuses about 'fiction'," a spokesman for the London Muslim Centre told me at the time, "The nature and quality of the insult is what matters. If someone insults your wife or children, will you not retaliate? And if they insult your God, who means more to you than anyone, will you not retaliate more?"

Suddenly, religion, rather than kingship or political power, became the authority you couldn't mock or play with. In 2005, the Jyllands-Posten Danish newspaper published 12 cartoons that portrayed the prophet Mohammed humorously (in one, he wears a turban with a fizzing bomb-fuse). The paper claimed it only wanted to contribute to the debate about Islamophobia and modern sensibilities; but there was uproar. Danish Muslim organisations filed a judicial complaint against the Jyllands-Posten. Muslim protests broke out around the world, in which a reported 200 people were killed. Churches, Christians and Dutch diplomats were all attacked.

The Jewish lobby has not been slack in objecting to portrayals that seem to slight their racial identity. In 2003, The Independent was both attacked and praised after a cartoon by Dave Brown appeared showing the then Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon, devouring an Arab baby – a steal from Goya's Saturn Devouring His Children. Complaints flew from Jewish organisations. The cartoon was adopted by radical Islamic groups in India, as part of their virulently anti-America and anti-Israel campaign. And the British Political Cartoon Society annointed it its Cartoon of the Year.

Gerald Scarfe strayed into the same waters in 2013 when he published a cartoon showing Benyamin Netanyahu building a wall with the dead and bloodied bodies of Palestinians, bearing the caption: "Israeli elections – will cementing peace continue?"

The work was published, by misfortune rather than design, on Holocaust Memorial Day. The Board of Deputies of British Jews and the European Jewish Congress both accused Scarfe of anti-Semitism, and of perpetrating the ancient "blood libel" against Jewish people, but many high-profile Jews argued that they were wrong. Rupert Murdoch, owner of The Sunday Times, issued a grovelling apology.

If you want to contemplate an old-fashioned relationship between the cartoonist and the authority he lives to subvert, however, look at the case of Ali Farzat. He's Syria's most renowned political cartoonist, head of the Arab Cartoonists' Association and holder of the Sakharov Peace Prize. Bashar Al-Assad was a fan of his early cartoons, and the two became friends. In 2000, Farzat founded al-Domari, a Syrian version of the French satire magazine Le Canard Enchainee; it was wildly popular, but forced to close by relentless government censorship.

As the Syrian civil war got under way after 2003, Farzat's cartoons became more blatantly anti-regime and anti-Assad. Then in August 2011, retribution came. Farzat was pulled from his car in central Damascus by masked men with guns. They beat him up, broke both his hands, took his briefcase and drawings and left him with a warning: "You don't satirise Syria's leaders." Farzat's response was to wait for his hands to heal. He has no plans to retire from holding Assad to account.

"I was born to be a cartoonist," he said recently, "to oppose, to have differences with regimes that do these bad things. This is what I do." It is what they have been doing since the 1780s.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments