'Excessive' surveillance knocks UK down table for 'free and open web'

Even Chile, Uruguay and South Africa beat us in the WWWF index

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A lack of privacy from online state surveillance has caused the United Kingdom to fall beneath Chile, Uruguay and South Africa in its reputation for a "free and open" Web, according to a new global index.

The UK's "poor" record on online privacy damaged an otherwise strong record in using the Web, causing it to trail behind Scandinavian countries in the annual Web Index Report, with Sweden heading the table and Norway placed second.

The World Wide Web Foundation (WWWF), which produces the index, commended the UK for the richness of its web content, saying users were empowered with the availability of relevant material. But the UK's score was marked down heavily for excessive levels of state surveillance.

"Whilst the UK ranks third in the overall Web Index, it plummets to 24th on the Freedom and Openness sub-index, ranking below nations such as Chile, South Africa and Poland," Anne Jellema, the ceo of the WWWF told The Independent. "The Web Index throws the scale and scope of government spying into stark relief."

The findings follow new claims that the UK allowed America's National Security Agency to keep the mobile phone numbers and email addresses of ordinary Britons from 2007. The claims were based on documents leaked by NSA whistle-blower Edward Snowden.

Ms Jellema said only five countries of the 81 in the index meet best practice standards for privacy of electronic communications, meaning both an order from an independent court and substantive justification must be provided before law enforcement or intelligence agencies can intercept electronic communications. Information on the granting of such orders must be made public, she said.

"The UK in fact performs even more poorly than the USA. In the UK a non-particularised warrant (a 'certificated warrant') is sufficient for relevant agencies to intercept evidence, whereas in the USA there is provision for a form of court oversight, albeit a very weak one."

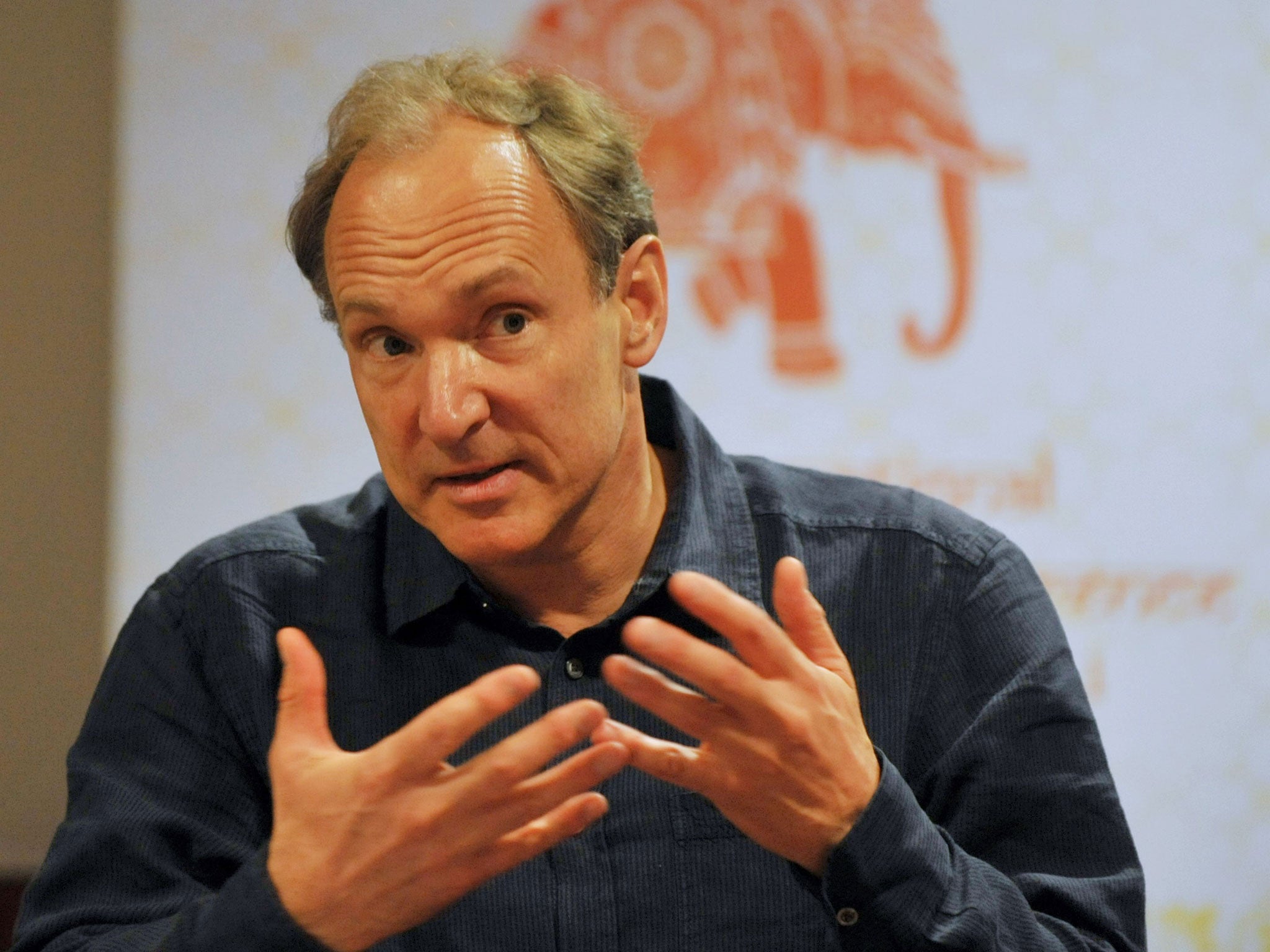

Responding to the findings, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web and founder of the WWWF, applauded growing efforts internationally to identify and challenge state surveillance.

"One of the most encouraging findings of this year's Web Index is how the Web and social media are increasingly spurring people to organise, take action and try to expose wrongdoing in every region of the world," he said.

"But some governments are threatened by this, and a growing tide of surveillance and censorship now threatens the future of democracy. Bold steps are needed now to protect our fundamental rights to privacy and freedom of opinion and association online."

The Philippines, which was placed 38th, was the highest placed developing country in the index.

But an accompanying report from the WWWF highlighted large wealth-based disparities in Web access. "Wealthier groups in most countries are increasingly using the Web and social media to gain knowledge and amplify their voice in public debate," it said. "However, groups such as low-paid workers, smallholder farmers, and women in the developing world are much less likely to be able to access vital information online."

The report also identified a "global trend" in greater online censorship.

"Recent advances in technology have outpaced both engineering safeguards and legal frameworks to protect privacy, making it trivially easy for states to collect and retain vast quantities of data on entire populations," said Ms Jellema. "Our freedom to express ourselves on the internet has come to play a unique role in 21st century democracy. If we don't want to lose it, we urgently need a broad democratic debate on appropriate limits to state surveillance power in the digital era."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments