Loveless: How Russian director is taking aim at life under Putin through the ugliness of divorce

Andrey Zvyagintsev’s film ‘Loveless’, which has been Oscar nominated for best foreign language film, is his latest critique of Russian society

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

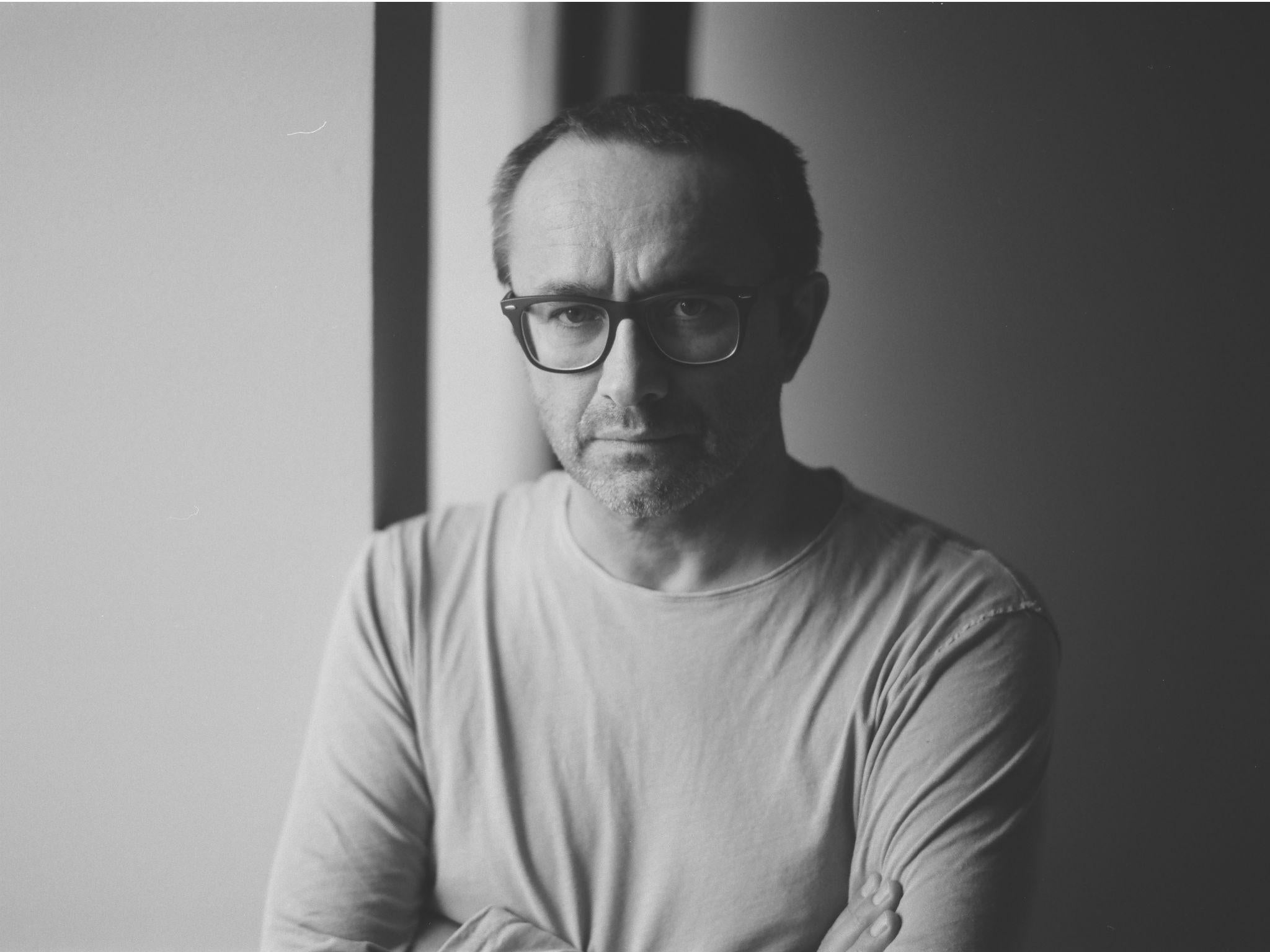

How do you follow up a film (Leviathan) that divided audiences in Russia and won you an Oscar nomination? Well Andrey Zvyagintsev seems to have found the answer with his latest critique of Russian society, Loveless.

Loveless tells the story of how a separating couple react to their 12-year-old son going missing after one of their fights, which coincides with the news reporting on a Mayan prophecy about the impending apocalypse. The two stories are unrelated. Naturally the foremost Russian director working today, Zvyagintsev doesn’t make the film you’d expect. The parents, Boris (Aleksey Rozin) and Zhenya (Maryana Spivak) have two of the most ugly personalities you’re likely to see on-screen this year. But in highlighting their self-interest and egoism it soon becomes apparent that the 54-year-old is taking aim at Russian society under President Vladimir Putin.

Zvyagintsev is a precise, formal and classical filmmaker. Every shot is perfectly composed and replete with meaning. So perhaps it’s no surprise that when we meet at the Picturehouse Central in London his desire for accuracy makes him question whether the English title for the film is right or not.

“The English translation of the title does not fully convey the weight and meaning of the Russian title which is literally non-love, the opposite of love, not devoid of love which is what loveless implies,” he states through a translator, although it becomes clear during the course of the interview that he understands English. “It’s not hate, it’s not indifference, it’s hard to say and the reason I brought this up is because the Russian title sounds even more pessimistic.”

As we watch the couple who are going through a bitter divorce and see their desires and interactions, it becomes clear that the director is taking aim at the way capitalism and competition has affected Russian life in the post-Communist era. “To use other people as tools for your own purposes,” he begins. “This lack of empathy and this striving towards success, materialistic success is the basis of contemporary society, what is termed a capitalistic society.”

It creates people with distance from one another. The missing child doesn’t change the relationship between the couple or bring them together in any way, and the director takes a pop at the tendency in cinema to brush over the ugliness of humans. “A version of the story has been told many times where good always prevails and there will be an inevitable happy end. It’s like Novocaine for the soul – don’t worry everything will be alright, so I’m tempted to look at it from a different angle and not look at life as a fairy tale, to look at what is really happening, can this injection of truth into our system be a stimulant and force us to rethink our attitude towards life and change our lives. Maybe it could work this way.”

The director would love to see a change in the way Russia functions and works. He has called for free elections in Russia and has never voted because he doesn’t believe that his vote actually counts. He supported the opposition figure Alexei Navalny, who was recently barred from standing for election.

He questions whether Russia is any freer today then it was when under Soviet rule. “They think it’s good to somehow install into the minds of Russian people that Stalin was not too bad,” he exclaims. “That he was an efficient manager who managed to take that peasant country and raise it to industrial progress and that it was a huge achievement. They are trying not to talk about the human sacrifice needed to make this happen. The authorities they have nothing new to offer so they are almost inevitably going back to the past.”

This is Putin, I clarify; “Precisely.”

In the mother in the film we see Mother Russia. And the director adds, “What’s really important for me is the tragedy [of their son going missing] that she has gone through. One might believe that the tragedy would have changed her life and taught her something about life, but in fact we see that nothing has changed, she is still on the same treadmill and doesn’t seem affected by it.”

Loveless has been nominated for a best foreign language film Oscar. Leviathan, which contained criticisms of the state, received government money and was put forward for the Oscars by Russia as its best film. I ask if the fact that a Putin-led Russia was able to put forward both Leviathan and Loveless for the Oscars was a sign that the government was more liberal than depicted given the implicit criticism contained within the films. He counters that rather it shows there has been some progress, “Thank God. This film was on general release in Russia, no one hindered its distribution and it is indeed a sign that it’s hard to pull back entirely, to get back to the past when films were shelved and banned. It would be impossible to overnight return the whole system to an isolationist state.”

Since he grew up in Siberia, where he idolised Al Pacino and wanted to be an actor, Zvyagintsev has lived under regimes that have left him bemused by the scheming of the politicians and the suffering of the people. “Capitalism is indeed slavery. Whatever is your deity, whether it’s the rouble or the dollar or the phantom of communism, you are not free, you are enslaved.”

His career as an artist started as an actor on TV soaps and commercials. He doesn’t miss it much. He received immediate acclaim when his beguiling first film, The Return, won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 2003. His second film The Banishment is the only one that hasn’t met with acclaim. 2011’s Elena saw him become more directly critical of Russian society and then with Leviathan, which includes a scene where the faces of Russian leaders are used in target practice, he started to move for the jugular.

I ask him what his own parents think of his films, given that he often shows innocent youths against the compromised adults. “My mother is in love with every word I say, let alone my movies,” he giggles. “My father he left when I was 5-years-old and became a stranger to me. He’s been dead for a few years now and so I will never know what kind of man he was. After he left, my father had two other children, and his daughter, my half-sister, wrote to me when The Return came out, when my father was still alive and revealed that after he watched the film, he went onto the balcony in Tomsk in October, and stood there smoking heavily for a full hour in the cold.”

‘Loveless’ is out on 9 February

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments