In New York, officer suicide is a growing problem

An average of five officers per year have taken their own life in New York City, and activists say that mental health services need to be expanded

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

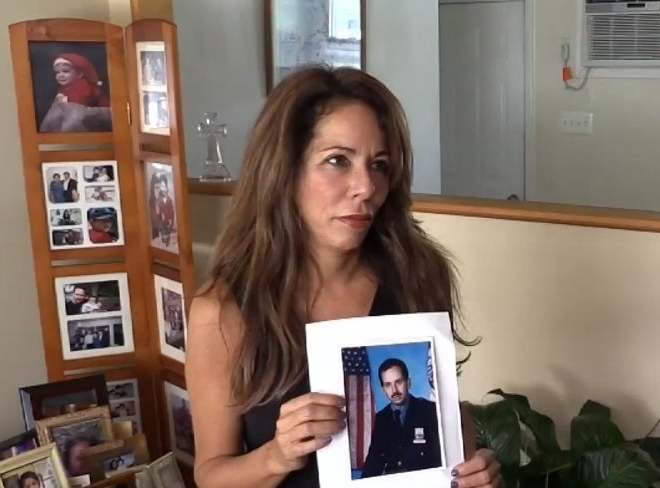

Your support makes all the difference.As soon as Eileen Echeverria saw detectives walking up to her home in a quiet Long Island hamlet, she said she knew why they had come. For more than two months, Echeverria, the sister of a New York City Police Department officer, pleaded with department supervisors to take away her older brother’s service weapon. She believed he was dangerously unravelling under emotional problems and crippling debt.

Her fears were realised: When they got to the house, the detectives confirmed that her brother, Robert Echeverria, 56, had shot himself in his home in Laurelton, Queens, and had died at a nearby hospital. “I begged you to get him help,” she told the detectives. “I didn’t just ask. I sobbed, please. I knew this was the end.”

Robert Echeverria’s death on 14 August was the ninth officer suicide this year in New York City, a record for a department that has struggled to identify troubled officers in its ranks and direct them towards help. Other cities, including Los Angeles, Chicago and Houston, have lowered the number of suicides in their police forces with aggressive mental health initiatives, including efforts to remove the stigma of seeking counselling by making therapists visible and readily available.

But New York City, where an average of five officers per year have taken their own lives since 2014, has lagged behind its peers, says Donovan Richards, a city councilman from Queens who leads the council’s Public Safety Committee, which oversees the Police Department. “We have allowed this to fester for too long,” says Richards, one of several sponsors of a new bill that would expand access to mental health care for the department’s employees of all ranks.

The bill would direct the department to make dozens of added therapists available to officers and would help connect officers seeking aid with annual mental health checkups and peer support groups. A joint city council committee will take up the bill, which has the support of the police department, at a hearing this week. It is expected to pass soon. “These are things the department isn’t doing right now,” Richards says. “We need to make sure mental health services are the norm.”

After four officers took their own lives in June, police commissioner James P O’Neill called the situation a crisis and urged troubled officers to seek help from department chaplains, peer support groups or phone and text hotlines.

The department has since launched a number of initiatives, including mandatory one-hour suicide-prevention courses called “Shield of Resilience”, which are designed to address problems specific to law enforcement. About 50 therapists would be added to the “cadre of dedicated mental health care workers doing evaluation and outreach work and making referrals for our officers,” says department spokesperson Al Baker.

We need to make sure mental health services are the norm

Blue Help, a nonprofit organisation that tracks law enforcement deaths by suicide, has tracked that at least 146 active-duty and retired officers have taken their lives so far this year in the US. The group’s president, Karen Solomon, says that when you consider the size of the New York City Police Department – about 36,000 officers – its suicide rate may be comparable to other agencies around the country. “There are departments with less than 200 officers and you have two suicides. That’s higher than the NYPD,” Solomon says. “Smaller departments have higher rates statistically, but we don’t hear about others because they are not the NYPD, America’s police department.”

Police officers are at a higher risk of suicide when compared to civilians because of job stress, access to firearms and peer pressure to hide their emotions, says Jim Pasco, an executive director with the National Fraternal Order of Police, which represents half of the country’s police force. Despite the high-risk factors, most officers are reluctant to see a therapist for fear of losing their assignments, shields and service weapons, says Tom Coghlan, a retired New York detective who founded Blue Line, a counselling centre for law enforcement officers.

Even by merely seeing a therapist, officers must contend with practical implications of alterations to their schedules and availability to earn overtime, he says. “They feel it would hurt their careers. You take away what makes them a cop,” Coghlan says. “They are the ones who run to help others.”

Other cities, better strategies

Other large urban police departments are seeing fewer suicides when they narrow the gap between officers and counsellors. In Los Angeles, for example, the department has gradually hired a “small army” of therapists, 16 and counting, who frequent neighbourhood police stations and even ride along with officers to better understand their job pressures, says Denise Jablonski-Kaye, a psychologist in the department’s Behavioural Sciences Services unit.

Therapists also learn police culture and lingo to better connect with officers, who then often feel more at ease seeking help for addiction, anxiety, stress and other emotional problems, Jablonski-Kaye says. “After a session, they get up and say, ‘Thanks doc, I feel so much better,’” she adds. “They learn it is OK to talk to someone.”

The Los Angeles Police Department, one of the nation’s largest police forces, had one suicide in the past two years, she says.

In Houston, therapists have also become familiar faces in the department’s various neighbourhood police stations, says Art Acevedo, chief of that city’s police department, the fifth-largest in the country. The department has seen only one officer suicide in the last three years, Acevedo says. The tactic has allowed often hardened officers to open up.

“Twenty years ago, a police officer would never go to a psychologist asking for help,” Acevedo says. “Now we tell them, ‘We stand with you. And we are praying for you’.”

Officials at the Chicago Police Department, which confronted a similar crisis to New York’s when 11 officers took their own lives in a recent three-year span, said they wanted to mimic the success Los Angeles and Houston have had with their programmes. Aside from hiring more therapists, Chicago’s department also added chaplains from different denominations to serve an increasingly diverse police force, says Anthony Guglielmi, a department spokesperson.

Police officers in Chicago seem to be responding to the changes, Guglielmi says. “Often officers contact one of the chaplains when they are having issues,” he says. “Our police force is changing. We need to reflect that.” Chicago has had three suicides this year, after four last year, Guglielmi says. “We haven’t had an incident recently, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t coming,” he adds.

‘Here I was, a gun in my mouth’

The officers in New York who killed themselves range in age and rank, from a 35-year-old recently engaged patrol officer to a 62-year-old deputy chief facing mandatory retirement. “There is no rhyme or reason. There is no profile. There is no pattern,” says Coghlan, the former detective turned therapist.

There is no rhyme or reason. There is no profile. There is no pattern

Relatives of the nine deceased officers declined to be interviewed.

But there are signs that many officers are responding to pleas not to turn to suicide. John Petrullo, director of the nonprofit Police Organisation Providing Peer Assistance, says there has been an uptick in callers. “They want to reach out,” says Petrullo, a retired officer. “What we do is listen, let them get it out of their chests.” When a caller expresses serious intentions of self-harm, they are referred to a licensed therapist immediately, he says.

The challenge for police officials is to connect officers in need with available resources. Keith McGurk, 40, a retired New York City Police Department officer, says he attempted suicide in 2009. He recalls that he had limited resources to help him cope with issues such as a disciplinary hearing at work and a custody fight for his daughter.

“I couldn’t see a way out. I was unfixable,” he says. “Here I was, a gun in my mouth. It was a cold bitter taste.” A recovering alcoholic, McGurk says he wrote two suicide notes and drank himself blind to muster the courage to kill himself. Several hours later, McGurk says he woke up and found himself in Maryland, a 9mm handgun next to him on the passenger seat of his car. A hostage negotiator talked him to safety.

Now living in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, McGurk has married the woman he once fought in court, reunited with his daughter, now 18, and has two sons. “Suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem,” McGurk says. “The department needs to do more. My happy ending can happen to everybody.”

The department needs to do more. My happy ending can happen to everybody

Pleas that went nowhere

Eileen Echeverria says initiatives like the proposed expanded mental health care programme have the potential to save the lives of officers like her brother, who she suspected suffered from undiagnosed depression and other mental health problems for years.

The son of Cuban immigrants, Robert Echeverria dreamed of carrying a gun and a badge while growing up in West Islip, on Long Island.

After graduating from State University of New York at Brockport, he joined the police when he was 31, after several attempts to pass all the necessary exams. He was assigned to the 73rd precinct in Brooklyn, where he met his future wife, Sheila; they have two children, Robert Jr, 18, and Faith, 11, Eileen Echeverria says.

She recalled that her brother would ramble about unexplained body scratches, bruises and incidents of alleged bullying at work. He once complained that he found a dead rat in his locker early in his career, and that haunted him, she says. Echeverria says she never knew for sure whether her brother had actually been bullied. He also confided to her that he had marital problems, job stress and financial struggles, she says.

By early June, Echeverria was so troubled by her brother’s behaviour that she reported it to a police supervisor and a department therapist. He was asked to turn in his gun later that month, she says. She later learned the department returned the weapon to her brother a few days later.

In emails reviewed by The New York Times, Echeverria pleaded with Internal Affairs Bureau officials to reverse course. Her pleas went ignored, she says. The department, which is looking into Echeverria’s claims, declined to comment on an active investigation.

During an emotional funeral, more than 200 uniformed officers and relatives remembered Robert Echeverria as a dedicated father and police officer. Robert Jr clutched his father’s police hat. An officer folded a white and green flag that hugged Echeverria’s black coffin during the service and then handed it to his sobbing widow. His daughter, Faith, rested her head on the flag and cried out, “Dad!”

“Something has to change,” Eileen Echeverria says, a day later. “How many more police officers have to die?”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments