The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Where did all the flying saucers go?

The real mystery of UFO sightings, writes Andy Martin, is not where they came from but why extraterrestrials stopped visiting Earth

They’re back. Maybe they never really went away. But now UFOs are popping up on our radar screens again. Recent accounts from US navy pilots report sightings of multiple aerial phenomena – “spinning tops” or “discs” or “strange objects” – that can’t be accounted for in terms of current terrestrial technology. They can soar and dive, accelerate, slow suddenly, then hit hypersonic speeds, all without any apparent engine or exhaust plume. Video footage shot on a plane camera, dating from 2015, has the pilot exclaiming, “Wow, what is that, man? Look at it fly!”

I was starting to think that extraterrestrials had given up on Earth tourism. But it is not so long since sightings of flying saucers were as common as planes stacking up over Heathrow.

The first use of the words “flying saucer” to refer to a spacecraft goes back to a Hearst International press release of 26 June 1947 (“UFOs” didn’t appear until 1952). Kenneth Arnold was an American commercial pilot. He was supposed to be looking for a marine transport plane that had been lost over Washington state. He didn’t find the plane, but – on 24 June – he did report seeing nine disc-like objects moving at 1,200mph in the sky over the Cascades mountain range. His account was taken seriously enough to be investigated by two military intelligence officers – who then allegedly died when their plane mysteriously crashed. Arnold went on to collaborate with Ray Palmer, editor of science fiction magazine Amazing, which also published Isaac Asimov.

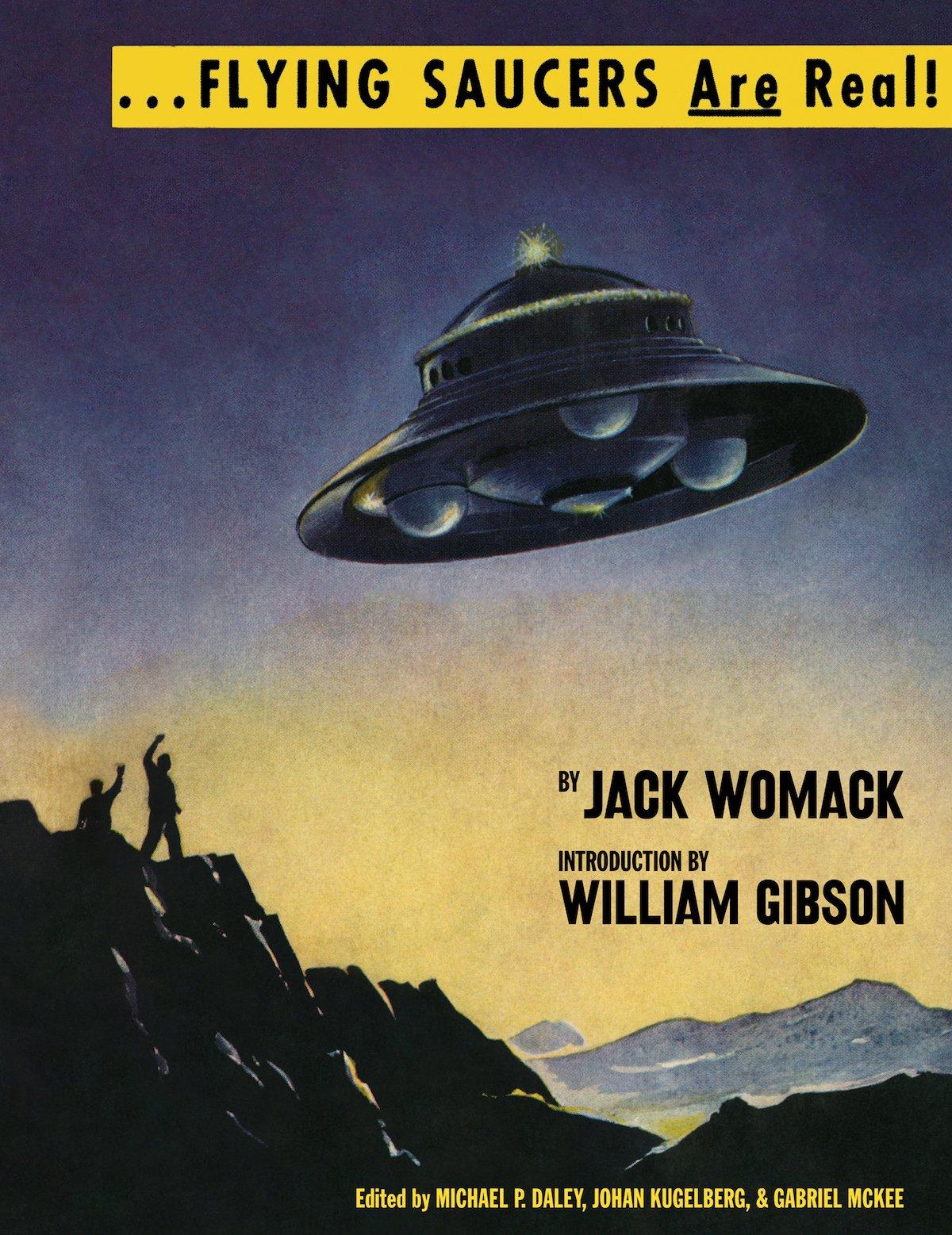

It’s a classic 20th-century tale, hovering between fact and fiction, of the kind that has been exhaustively catalogued by Jack Womack, a writer of “speculative fiction”, born in Kentucky. His library is now stored at Georgetown University in Washington DC, but edited highlights, reports and “photographs” from around the world over a 50-year period, are collected in his gloriously nostalgic book, Flying Saucers are Real!

It was an era when book blurbs could be penned by aliens. “SPACE MEN URGED THE AUTHOR TO COMPILE THIS BOOK, SUPPLIED MUCH OF THE INFORMATION AND APPROVED THE WORK” appeared on the front cover of Flying Saucers Close Up by John W Dean (1969). In 1949, Frank Scully (whose name would be immortalised by The X-Files’ Dana Scully) broke the story of a crashed saucer in the Arizona desert, from which alien bodies had been removed – and the whole thing was hushed up and buried by the military. It made no difference to Scully that the “sources” of his “scoop” turned out, on not very close inspection, to be serial fraudsters. Scully wrote of one of them, posing as a scientist called “Dr Gee”, that he had “more degrees than a thermometer”.

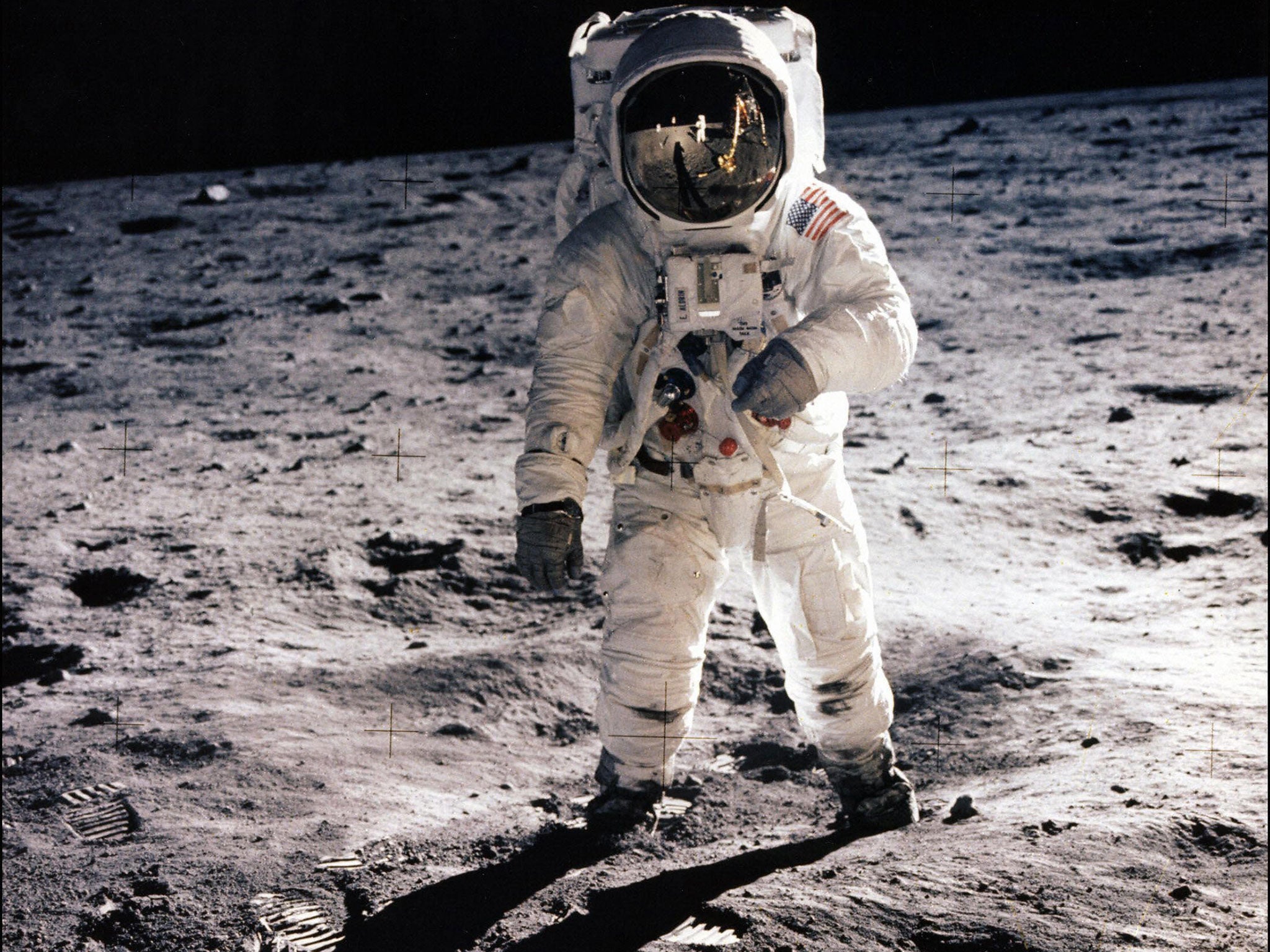

The Cold War was the high tide of Close Encounters of the Third Kind. America might be locked in conflict with the Reds, but flying saucers represented a celestial force capable of transcending and obliterating all terrestrial disputes, with far greater power than mere H-bombs. Mysterious government agencies were always said to be looking into the matter. But there were always “cover-ups”.

Unlike ET (or, for that matter, Alien), aliens of the period are generally Nordic-looking, rather beautiful, infinitely wise. George Adamski, a resident of Laguna Beach, started off writing SF but converted to non-fiction and wrote a successful trilogy, The Flying Saucers Have Landed, Inside the Space Ships and – poignantly – Flying Saucers Farewell. He claimed to have met a Venusian (called Orthon), and had a secret meeting with the Pope. The only seriously weird aspect to the visitor was that “His trousers were not like mine”.

It was never going to be enough just to observe. There had to be a conversation (of the telepathic kind). George W Van Tassel wrote I Rode a Flying Saucer. Truman Bethurum met a spacewoman named “Aura Rhanes”. His wife was sceptical though: “I’ve come to the conclusion that you’re just trying to make me jealous through all this mention of hours talking with some beautiful spacewoman, so you can get me up there. Well, it won’t work. I’m not jealous. And I’m not coming up there in all that heat.” One man ended up marrying the earthly incarnation of a willowy blonde alien. After War of the Worlds, the zeitgeist moved on to make love, not war in books like Those Sexy Saucer People.

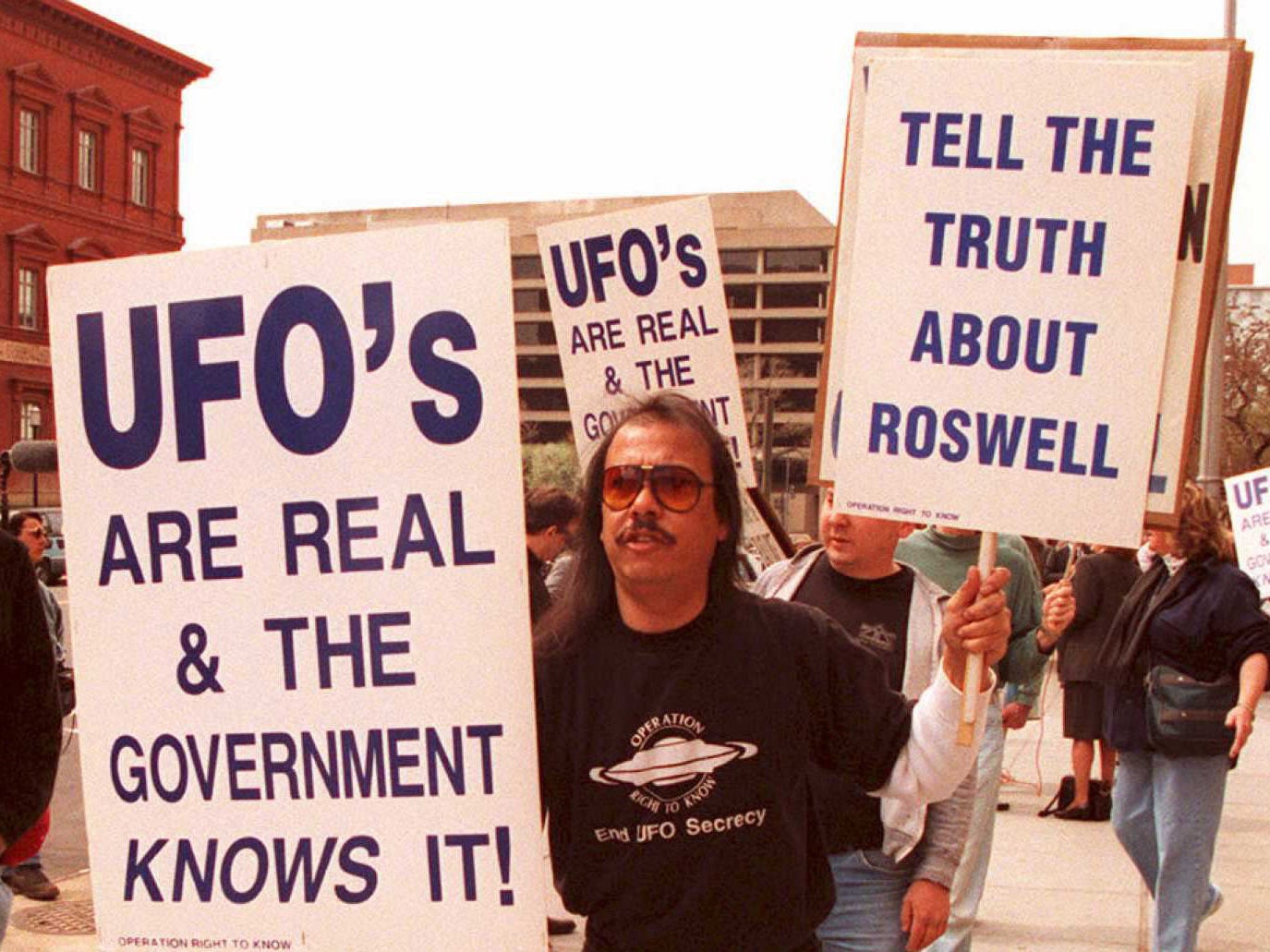

Back in Britain, saucer “clubs” sprang up around the country. They invited Cedric Allingham to come to give them a talk. He was the author of Flying Saucer From Mars (1955), in which he relates his meeting with a Martian while on holiday. He remained elusive. They persisted, begging Allingham to make a public appearance. Eventually, his publisher wrote to say that, alas, the author had gone to Switzerland, but had fallen down a mountain and died. I once attended the annual conference of the British UFO Society in Sheffield in the 1990s, dedicated to the Roswell incident (harking back to 1947 and another crashed saucer and more alien corpses, warehoused in Nevada’s Area 51). I was about the only guy in the pub who had not had a fling with an alien.

The first flying saucer convention was held in Los Angeles in 1957 at the Hollywood Hotel. The connection with Hollywood is not coincidental. Nor that there is a “con” in “convention”. Hollywood, it hardly needs saying, embraced aliens. The fundamental premise of Men in Black, that creatures from other worlds are ubiquitous, is true of terrestrial culture. From Independence Day to Arrival to Avengers: Endgame, we are under siege from imaginary extra-terrestrial immigrants.

But actual abductions – being beamed up into a craft poised overhead – seem now less common than they once were. In 1965, under hypnosis, Barney and Betty Hill of New Hampshire claimed that their car had been stopped and they were taken aboard a spacecraft where they were interrogated and probed by “small, humourless grey beings”. Betty Hill wrote about her experience in A Common Sense Approach to UFOs (1995).

The Harvard psychiatrist John E Mack, in his book Abductions: Human Encounters with Aliens (1994) took these accounts seriously and wrote about them sympathetically. He collected more than a decade of cases and thought of them generally as an attempt to circumvent restrictive, materialist or “Cartesian” rationality. He was then duly investigated by a clandestine committee at Harvard, presumably because they started to doubt his sanity. Defiantly, he went on to write Passport to the Cosmos: Human Transformation and Alien Encounters (1999) before – in accordance with the UFO script – he was killed in a road “accident” in London in 2004, mowed down by a “drunk” driver.

In the foreword to Flying Saucers Are Real!, the science fiction writer William Gibson argues that “the truth, all these years, hasn’t as The X-Files had it, been out there, but rather was in here”, ie in psychic space. His mother once saw a flying saucer: but she needed to see one, he believes, living in rural Tennessee, largely on her own, riven by loneliness and anxiety. Aliens would at least be good company. Quite why they would bother with us is hard to explain. As one writer from Jupiter – communicating his thoughts through some poor earthling – neatly put it, humans are “the maximum gross densification of materialisation”. Something like the antithesis of God.

At the end of the 1950s, Roland Barthes, in Mythologies, deemed les soucoupes volantes as semiotic in inspiration, their seamless geometries compensating for our rough-hewn, organic irregularities, something like a Citroën déesse of the skies. In Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Sky (1958), CG Jung puts them down to a collective hallucination, “a universal mass rumour”, a substitute for religion in a godless world. He also pointed out that such sightings were not the preserve of the post-Second World War world. In 1566 in Basel, it was reported that “many large black globes were seen in the air, moving before the sun with great speed and turning against each other as if fighting”. There is a further eye-witness account in Nuremberg of “ringscheiben” (round plates) going around the Sun in 1561. Jung notes the resemblance of the sphere shape to the mandala and sees all similar sightings on a par with dreams and alchemical mysticism. The cigar-shaped “mother ships” (first reported by George Adamski) are a phallic projection of the unconscious.

Perhaps flying saucers were the original “meme”, as William Gibson suggests. Jack Womack, who collected so much UFO memorabilia, doesn’t think that aliens are real. He sees saucers as an aerial conspiracy theory, roughly on a par with theories about the assassination of JFK. Conspiratorially enough, one man, Fred Crisman, who was once notionally in possession of metal from a saucer, was also spotted on the grassy knoll. Womack associates saucers with hoaxes, poetry, visions, folk myth and distrust of the government. The very first sighting “contains every ingredient for the perfect X-Files episode: mysterious lights in the sky, vanishing evidence, peculiar witnesses, scientific details absent of science, strange deaths, unexplained government involvement, cross-purpose conspiracies, puzzled investigators, a story held up as evidence even after its exposure as a hoax.” He labelled his own collection, “Human – All Too Human”.

The very first sighting ‘contains every ingredient for the perfect X-Files episode’

I would find it easier to deride flying saucers if I hadn’t seen one myself in December 2004 in Cambridge. I was not abducted (so far as I know), but I definitely wanted to be. I felt a definite pang when the craft flew off without me. I’m not saying it was terrestrial or extraterrestrial, but I just want to note the following facts. I wasn’t drunk or “on” anything. The vehicle, roughly the size of a small football stadium, was poised about 200 hundred feet straight up, parked in the sky as serenely as a bus at a bus stop. Perfectly still. Perfectly silent. It could have been a blimp or a zeppelin except for one thing: after a few minutes it took off across the fields at high speed in a zigzagging trajectory, still without making a sound. No airship can do that.

I find myself sympathetic to the Carl Sagan-inspired Seti – the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence – and the “Drake equation” that underpins it, suggesting a tally of somewhere between 1,000 and 100 million possible alien civilisations that are capable of communicating with us. The technical problem is contained in the poignant question posed by the Italian astrophysicist Enrico Fermi: “Where is everybody?” Shouldn’t we have heard from them by now? But then again, maybe we have.

As the French philosopher and theologian, Pascal, once said, looking out at the night sky, “The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me.” We are bound to want to populate them. Or as Elton John put it in “Rocketman”, “It’s lonely out in space”. Earthlings are lonely. Flying saucers seem like a solution, connecting up heaven and earth.

Flying saucers seem like a solution, connecting up heaven and earth

I spoke to Lynn Picknett, author of The Mammoth Book of UFOs (2001). She was the deputy editor of The Unexplained and living in south London when, in one night in 1983, around 2am, she saw her UFO. She was an insomniac, wide awake at the time, and staring out of the window. She saw two lights flying through the night sky close together, almost in tandem and thought, planes can’t do that. The two then fused into one, then split into five separate entities, and finally reunited as one and zoomed off at top speed. “The phenomenon is like the shape-shifter of legend – it takes many forms, you can’t pin it down. It seems to manifest intelligence. But,” she adds, very reasonably, “it could be there is an element of projecting culturally appropriate images.”

For me, the real mystery is: why did they ever fade away? Why didn’t my flying saucer ever come back? In a sense, this is a question posed by that wild-eyed classic of mystical archaeology, Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods? (1968). Once upon a time, aliens were all over the place, helping to build the pyramids and sketching out astral maps on the plains of Nazca. Fine, Erich – but why did they suddenly stop coming?

Look at a typical flying saucer (either in your mind’s eye or you can try looking out of the window). What do you see? Isn’t it rather like an eye looking right back at you? An eye in the sky? Flying Saucers Are Watching You (1966), published by Saucerian Publications, makes this clear. The odd paradox of human beings is that we are both paranoid, fearful that someone is keeping an eye on us, and yet at the same time desperate for someone to keep an eye on us, in a benevolent sort of way. An omniscient being once performed this function, but extremely wise, blonde aliens might do just as well, peering down out of their porthole windows. Rather like the apotropaic eye painted on the side of certain buildings (and now on the tail of planes belonging to a Turkish budget airline), their point was to ward off evil. Flying saucers were a talisman, our good luck charm.

If they have largely deserted us it is because our every move, our every purchase, every film we watch or book we read, is constantly tracked and monitored and watched over by the likes of Google and Facebook. How could we possibly wish for greater surveillance? I fear that the smartphone may have killed off the flying saucer.

But perhaps, like those poor aliens who died in the Arizona desert, they have only been buried beneath the massive, non-stop invasion of cranks, crackpots, craziness, hearsay, hoaxes, speculations, scams, myth and mysticism that is the internet. The post-truth is out there.

‘Flying Saucers Are Real!’ by Jack Womack, edited by Michael P Daley, Johan Kugelberg and Gabriel McKee, is published by Anthology Editions and Boo-Hooray

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’. He teaches at the University of Cambridge

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments