Gertrude Legendre: The socialite whose penchant for adventure led her into the hands of the Nazis

Never one for the quiet life, Gertie was unlikely feminist anti-hero whose hunger for experience steered her towards danger in wartime Europe, jeopardising multiple lives and imperilling some of America’s most closely held secrets

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

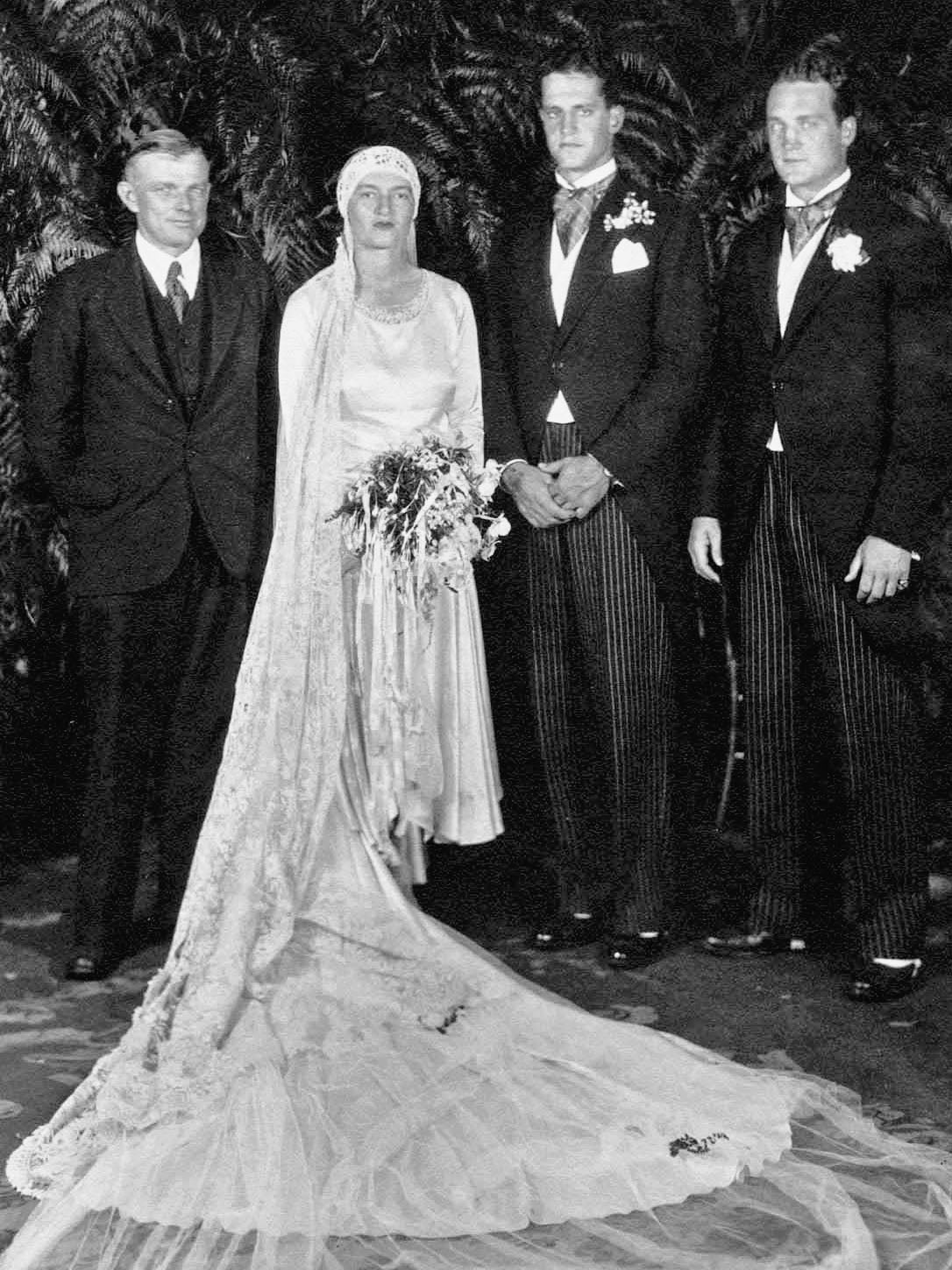

Your support makes all the difference.One afternoon in the summer of 1920, Gertrude Sanford sat on a log along a ridge in Wyoming’s Teton Range. The sun fell in bright shards through the treetops, but it was cool high up in the mountains, and the air was sweet with the smell of pine, fir and spruce.

Gertrude – known as Gertie – was wearing a Stetson hat, kerchief, lumberjack shirt, sheepskin chaps and boots. Her rifle lay across her lap, gripped tightly at the trigger guard as she waited in the vast silence for the sound of hoofbeats.

While most of her classmates were celebrating their high school graduations with debutante parties in New York City, 18-year-old Gertie instead insisted on an adventure out west. Shooting had been a part of her life since she’d picked off birds as a young girl wintering at the family home in South Carolina; she was an excellent markswoman before she reached her teens.

Later, at the all-girl Foxcroft boarding school in Middleburg, Virginia, she fox hunted, went beagling after rabbits and tracked racoon at night under the tutelage of the principal. It was an education in which “outdoor life ... was as important as the ‘finishing’ touches that we were receiving,” Gertie recalled in a 1987 memoir.

In Wyoming, Gertie’s party hired a pack train of ponies and, with a young cowboy as a guide, started to climb into the Tetons. Several days in, Gertie shot and killed a bull elk for the first time. “I was filled with pride and the exultation of success,” she later wrote. “I strode in to camp – all five feet five of me, every inch the successful huntress.”

Over the next seven years, Gertie would continue to hunt in Alaska and Canada – black and Kodiak bears, moose, caribou, mountain sheep and goats. “If I hadn’t gone on that first trip to the Tetons, I might never have known the thrill of life in the wilderness,” she said. Gertie enjoyed what she described as her “own safe extravagant world” gilded by great wealth – her family’s carpet and flooring business generated enormous resources – but felt that she “wasn’t going to be like most of the girls I knew. I wanted something different, something more than the social whirl.”

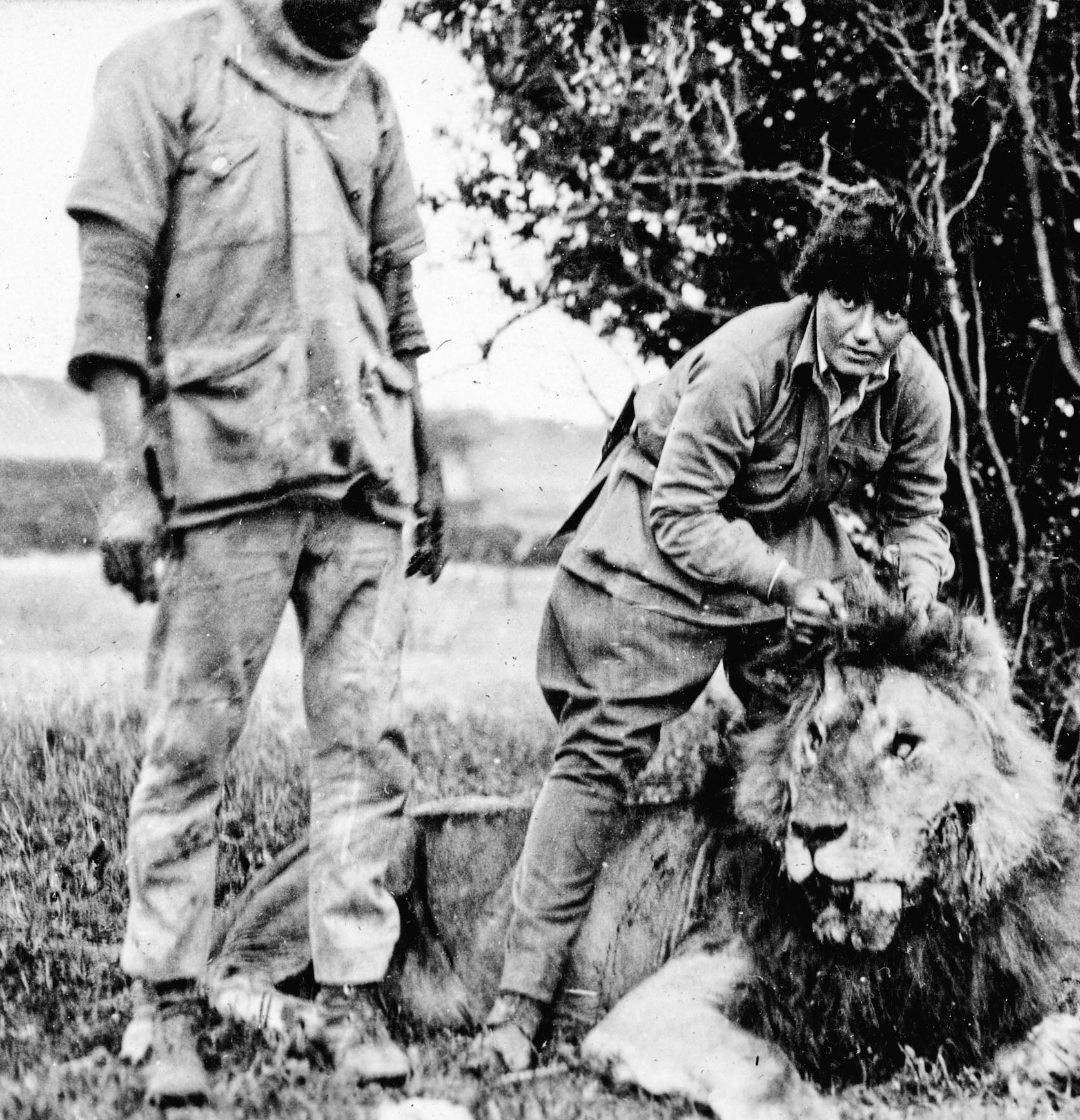

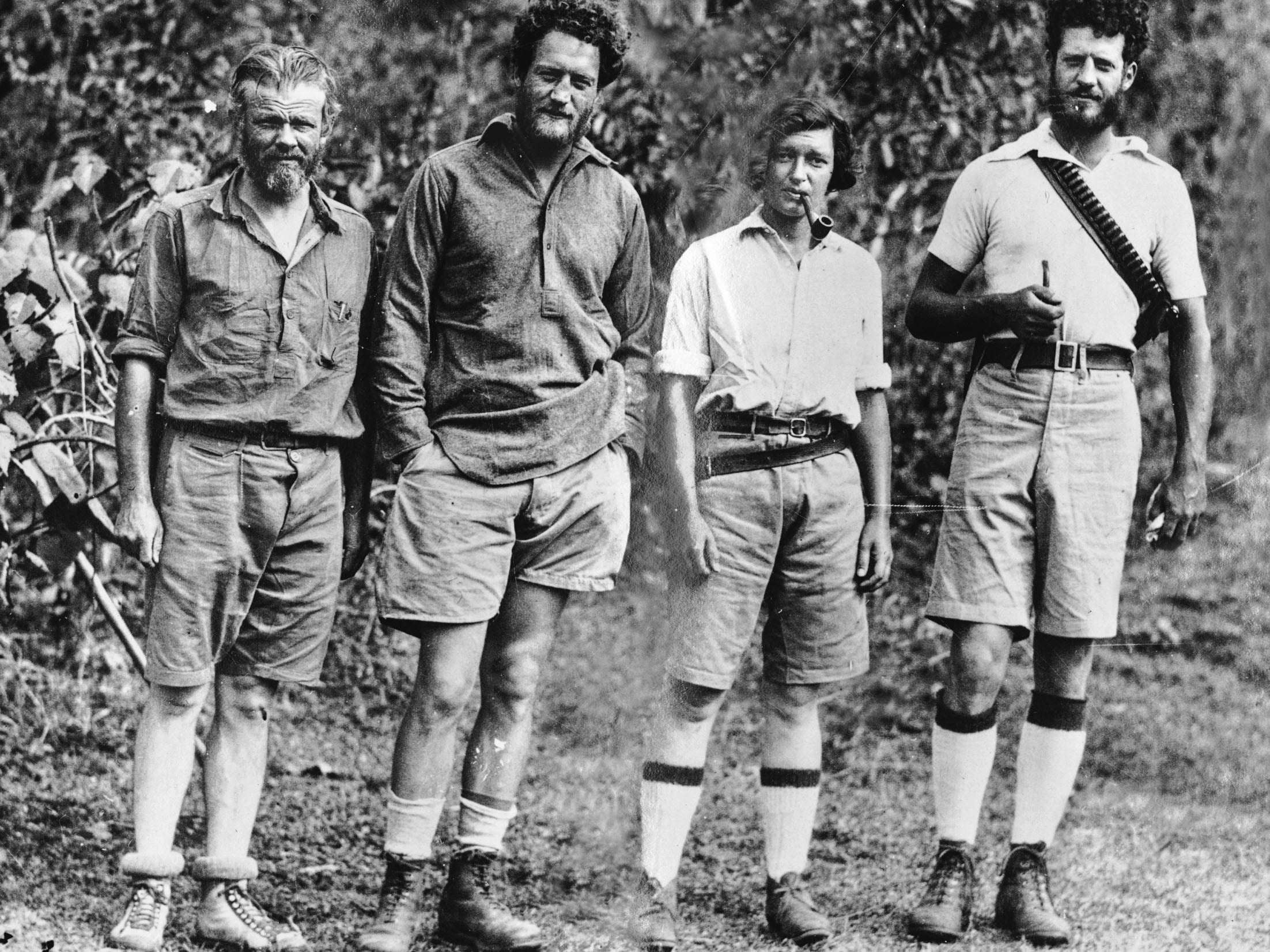

To be a woman in early 20th-century America and indulge that kind of restlessness and adventurous spirit was an unconventional thing, yet Gertie had the wealth and determination to push back at the gender norms that bound many of her contemporaries. Throughout the 1930s, she led multiple gruelling hunting expeditions in Africa and Asia and never faltered while some of those around her collapsed in exhaustion. (Her husband, Sidney Legendre, wasn’t quite as enamoured of the outdoor life: “I am not what you would call a vital person,” he said.)

At the beginning of the Second World War, she took a job – her first paid employment – to help the war effort but railed at the disparities in pay between men and women. “What burns me up the most is the unbelievable lack of confidence in a woman’s ability,” she said in a letter to her husband. “Men cannot bear to have their world encroached on by more efficient women. They hate to give way, they hate to admit they are good, they hate to give them power. It fairly drives me nuts.”

Prioritising adventure and globe-trotting over raising a family, Gertie bracingly actualised her personal philosophy: “I don’t contemplate life; I live it.” All but forgotten today, she was an unlikely feminist anti-hero – one whose hunger for experience would come with high costs: it would, eventually, steer her towards danger in wartime Europe, jeopardising multiple lives and imperilling some of America’s most closely held secrets.

What burns me up the most is the unbelievable lack of confidence in a woman’s ability

On 7 December, 1941, Sidney was reading the newspaper in the gun room at Medway, the couple’s plantation outside Charleston, South Carolina, when the phone rang. “Have you got your radio turned on?” his brother Morris shouted. “No,” said Sidney. “Then turn it on; the Japs are bombing Honolulu and have sunk some of our boats.”

Like much of the country, Gertie was dumbstruck, even though the flames of war had been consuming Asia and Europe. The fabulous world Gertie inhabited was upended; the American idyll was over.

Sidney was commissioned as a lieutenant in the navy reserve in early April 1942 and assigned to intelligence duties in Hawaii. Gertie also wanted to contribute. She sent a three-page resume to her friend F Trubee Davison, a former assistant secretary of war, in which she noted the number of countries she had visited, that she could shoot a rifle and a shotgun, spoke French fluently, and had considerable experience with outdoor photography, including the ability to develop and print her own work. “I am physically fit,” she explained. “Can walk 20 miles a day. Have unusual endurance and exceptional health.”

Davison wrote back that he had one possible lead for her: the new spy organisation led by William “Wild Bill” Donovan called the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Her background security check noted that “subject’s family have always been prominent socially and are reputed to have been extremely wealthy” and described her as being “100 per cent loyal to her country,” as well as “a person of unusual ability, energy, courage and resourcefulness. It has been said of her that she can ‘hold her own with any man, in shooting or riding’.”

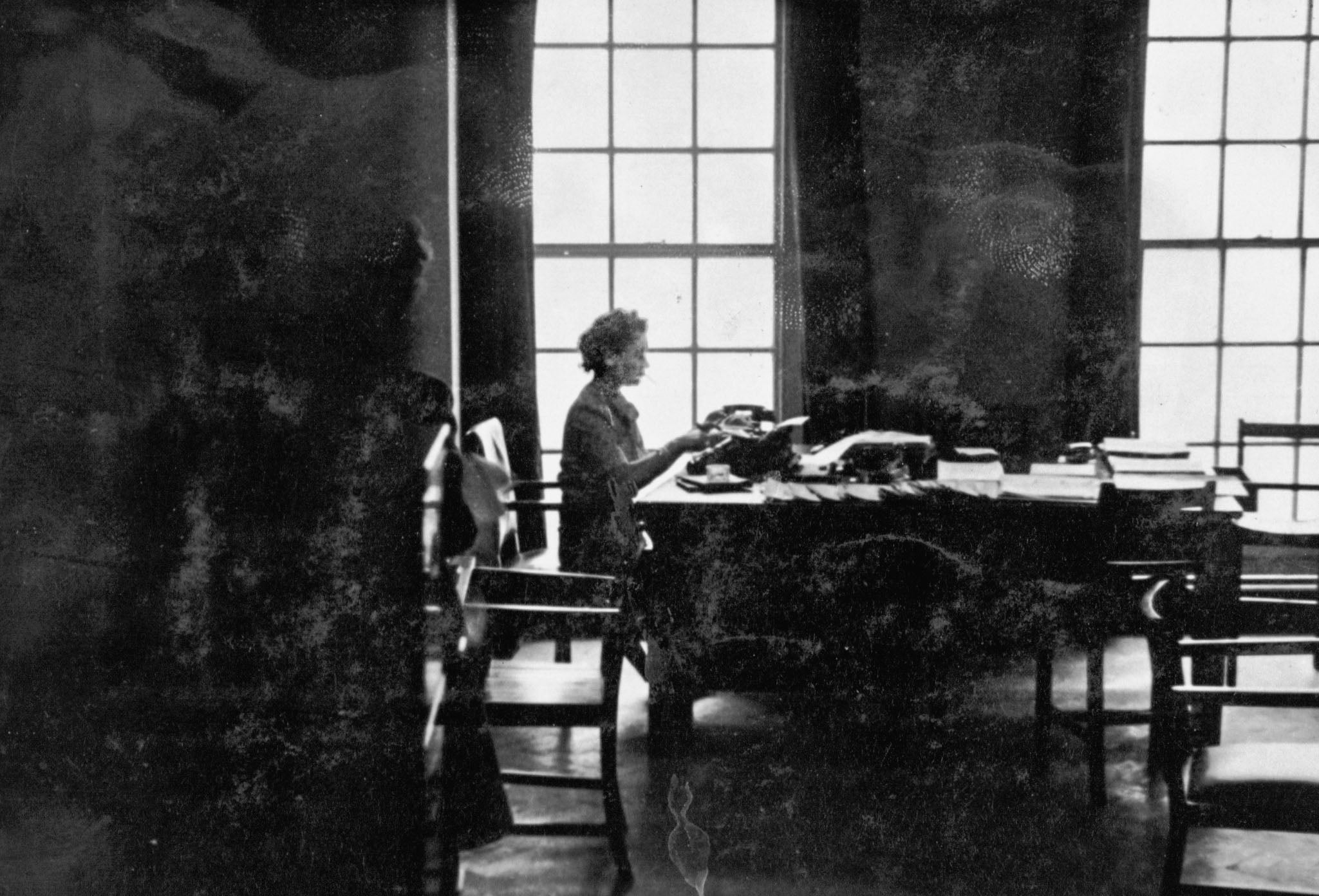

Gertie was hired and found a house in Georgetown for herself, her two-year-old daughter, the child’s nurse and a housekeeper. (Gertie and Sidney’s other daughter, then 9, was sent to the Foxcroft School, about 50 miles away in Virginia.) At first, Gertie was excited by her work and described her agency as “hot stuff”. Her job was to route all cables in and out of the OSS’ Secret Intelligence Branch, which gave her a broad if glancing view of OSS operations. On her desk was a battery of rubber stamps: “RESTRICTED”, “CONFIDENTIAL”, “SECRET”.

But soon, the first blush of her new life began to fade. She was desperate to join Sidney in Hawaii and plotted at every turn to make it happen, even though the navy did not allow the wives of officers to join their husbands. Washington became unbearable to her – “purgatory pure and simple. The crowds, the noise, the grey grim atmosphere”.

With Hawaii closed off, Gertie turned her attention to getting another posting. Donovan promised a foreign assignment, possibly to London or Cairo. “I told Colonel D that London was OK and I would like to go,” Gertie wrote to her husband. “I was really thrilled because my darling if I can’t get to you I would rather be ‘in the war’ close to things than stay here in this dreary town for the duration.”

Sidney was generally supportive of Gertie going to London but asked her to consider what it would mean for their children. Gertie noted in letters back that the girls would summer in Rhode Island without her in any case, and she was signing up for only six months; the separation might be short-lived.

As her younger daughter, Bokara, later said, she “didn’t much like children around”. Depending on their age, they lived separately in rented cottages and apartments with their nanny or at boarding school, visiting their parents on holidays and occasional weekends. Mothering was not her priority, Gertie told her husband in a letter. The “worlds to conquer type of thing always appeals to me, change, motion, new possibilities, new heights ... it’s my restlessness, my wander lust, my desire not to stay put forever in the same spot with the same scene, the same people and the same everything.”

My desire not to stay put forever in the same spot with the same scene, the same people and the same everything

In London, Gertie handled cables for all OSS sections. As each afternoon waned, a bell rang to draw the curtains when a nightly blackout descended on the city; London was being bombed, with air raid sirens blaring. Negotiating her way home with the help of a small faint torch in the pitch black was a challenge. “It’s black in the morning, black at night, and we live like moles all week,” Gertie told her husband.

When Sidney suggested some months later that Gertie end her tour, she rejected the idea. The limited six-month visit she had first spoken about was forgotten. Gertie was in for the long haul. “Why don’t I go back to Virginia and be with the kids? No doubt that is what I should do, and maybe that is my duty – but I just couldn’t go back and live in the country alone without you. It would be frightful. I far prefer Europe to Washington (which is my idea of the worst place on earth).”

After D-Day, Gertie felt restless. As early as November 1943, she had contacted an American friend about renting an apartment in Paris, all in anticipation of the liberation. “Every big shot I know is over there in the thick of it and I do feel so left out on the outer fringe of it all,” she told Sidney. “Gee, I wish I were a man so often – because then I wouldn’t be relegated to the sidelines.”

Finally, in September 1944, she got her wish: orders to join the new OSS office in Paris, where she would also manage communications. Gertie feared that the military campaign would end before she could witness the US army on the march. “Her obsession was to see the battle,” recalled a friend, who described her as “completely fearless” and with “the vitality of ten men”.

When she got to Paris, the OSS building was still being renovated, so the arrivals from London were free to roam. “During the day, I walked around Paris, amazed at how beautiful it still was,” Gertie recalled. The renovations were slow going, so her boss decided to give some of the staff a formal five-day leave. It was her first official break in more than a year, and she wanted “to turn up something interesting to do.”

On the afternoon of Friday, 22 September, she stopped in to the famous Hotel Ritz, where she found herself in the company of a group of American reporters. They were leaving the next day for Luxembourg, near where elements of the Third Army under Gen George Patton were headquartered. The chattering reporters prompted a stab of envy. “I wanted so desperately to see troops on the move, to actually feel the urgency of war, and to know more of what it really meant,” Gertie said.

I wanted so desperately to see troops on the move, to actually feel the urgency of war, and to know more of what it really meant

Gertie spotted Bob Jennings, a wiry, sandy-haired navy officer and First World War aviator. He was a friend of her husband’s; Gertie also knew him from London, where they had met several times at cocktail parties. He was scheduled to leave for London early the following week and from there to return to the US. Listening to the reporters, he, too, was soon infatuated with the idea of getting closer to the western front.

Jennings said he could borrow an old Peugeot convertible, originally German property but now with “USA” tags and an American flag sticker on its bumper. The car was a little dilapidated, he confessed, but it would get them there and back.

Paris was overcast when Gertie and Jennings set off early on the morning of 23 September. “We rode along straight roads of richly ploughed fields that looked the same as in peace time,” Gertie observed. “Only the occasional remains of a burnt out truck or tank gave one the feeling of war.” By noon the rain was pouring through the Peugeot’s rotted canvas top; Gertie tried to patch it, but the water kept pouring down their necks.

Later that afternoon, they blew out a tyre, then the Peugeot wheezed and died, forcing Gertie and Jennings to spend the better part of the next two days waiting for the vehicle to be repaired. A local mechanic said the parts could only be obtained in Luxembourg City, so they had the car towed there, where the mechanic said he needed 24 hours to fix it.

Time was running out, and soon they would have to return to Paris. The pair dolefully explored the allied-controlled city. “Convoys rumbled through the streets incessantly. Soldiers on the march, our countrymen going to battle, were everywhere. Their faces were so young, so full of eagerness and spirit,” Gertie said. This was some of what she had hoped to see, but the following morning at the Hotel Brasseur, over coffee and cigarettes, she and Jennings rued “the failure of our trip”.

At that moment, Jennings spotted a US officer entering the dining room – Jerry Papurt, a major working in X-2, the counterintelligence branch of the OSS. Jennings explained what he and Gertie were doing in Luxembourg. “We had a little extra time and thought maybe we’d mosey up to the line so the lady could hear some gunfire,” he said.

“I know where there is some gunfire. Think you could spare the day for a little trip?” Papurt asked.

“Where is it?” Jennings asked.

“Wallendorf,” replied Papurt. “Forty kilometres from here, just over the border ... It’s the first German town we took.” The town had been briefly taken by US forces, but they had just been ordered to withdraw, so they would not get too far ahead of American supply lines. Unbeknownst to Papurt, Wallendorf was back under German control.

Papurt said they could be back in time for lunch and Jennings and Gertie could return to Paris later in the afternoon, after picking up the Peugeot. The trio took off in a jeep driven by Doyle Dickson, a 20-year-old private from Los Angeles who was assigned to the OSS.

As the trip progressed, other traffic disappeared. Jennings, experiencing a frisson of unease, asked Papurt if he was sure they were on the right road. Looked like a good spot for an ambush, he said. Papurt spoke in German to the next farmer they passed, and he seemed quizzical about the presence of Americans but told them they would be able to see the village when they got around the next bend. He also said the front was close to 2 miles away.

All was quiet. As the houses in the village came into focus, there also didn’t seem to be any American presence. “Well, here’s Wallendorf, according to the sign,” said Gertie. “But I don’t see any...”

The whistling crack of a single shot cut her short. A bullet had hit the front fender. Gertie experienced a long moment of disbelief before she heard Papurt shout, “Sniper! He’s mine.” The major grabbed a rifle and ran behind a roadside hedge. As he crawled on the ground, he lined up his sight on a distant copse of trees from where the shot seemed to have come. There was no second shot, and after several minutes Papurt stood up and shrugged his shoulders. “If there’s anybody up there, I can’t see them,” he said.

Against all common sense and training, they decided to push on. Dickson hadn’t even gotten the car into second gear when a burst of machine-gun fire raked the ground in front of the jeep. All four jumped out; Gertie, Dickson and Jennings lay in a “cowering bundle” on the side of the jeep by a shallow ditch that provided some shelter from the attackers, while Papurt was on the exposed side of the vehicle. The Germans were firing a portable machine gun that could unleash over a thousand rounds a minute.

Papurt, in a quiet, unemotional voice, whispered, “They got me through the legs.” As Gertie tried to look around the tyre to see him, bullets whipped by her. Papurt called out, “Turn the jeep around. It’s our only chance.” Dickson jumped into the driver’s seat, but the vehicle wouldn’t start. “It’s kaput, sir,” he shouted.

A fresh round of fire erupted, and Dickson was hit as he tried to scramble from the vehicle. Jennings raced around and pulled the young driver back to the sheltered side. The private had been shot in the legs and shinbone, and his right hand had been shredded, leaving three of his fingers barely attached. Jennings urged Papurt to try to drag himself a little closer to the vehicle, then rushed out from behind the car and dragged Papurt back. Dickson’s wounds were bleeding freely, and he seemed “ghastly” to Gertie. She thought his lips looked faintly blue and his face was ashen, but he managed a weak smile as Papurt was placed close to his side. “Don’t worry, son,” Papurt said, assuring the young private that he’d get home to tell his war story.

There was, however, no obvious escape route. Gertie was too stunned to be frightened but did, in that moment, experience stomach-churning sensations of regret and guilt: that she wouldn’t see her husband again; that the OSS would be compromised; that she had been so damn stupid to get herself – someone, she thought, who should have remained an office drudge – into this jam.

Pinned down, the group decided to surrender. Jennings pulled a white handkerchief from his pocket and raised it on the barrel of Papurt’s carbine. The firing eased, then stopped.

Waiting for German soldiers to arrive, the four OSS members lined up their stories. Gertie would claim to be a file clerk and an interpreter for Jennings; Jennings would be a naval observer on a mission to the front; Papurt suggested he’d be an ordnance officer; Dickson, a GI. As to why they were in Wallendorf, the best explanation was the truth: They thought it was under American control and took a ride to see a small piece of Germany.

Gertie and the others were about to fall into the hands of the enemy. Gertie had no way of knowing that she would prove to be of deep interest to the SS, which ran a separate detention system for “special prisoners” who might be exploited to the benefit of the Reich; that she would spend the next six months being shuttled between interrogation centres, Nazi villas, hotels and private homes; that her capture would become a headache for officials back in Washington, who feared that she would be broken and disclose ongoing operations; that, though Jennings would survive the war, Papurt and Dickson would both be killed in the coming months when allied bombs hit the hospitals where they were being held.

Nor could she know that she would witness the collapse of Hitler’s Reich as no other American did, or that she would escape back to her life in the US – where she would live outside Charleston and die at the age of 97 – only by scrambling to freedom along train tracks by the Swiss border during the waning days of the war. All that would come later – long after the German soldiers emerged from the trees, approaching Gertie and her companions from two directions, guns levelled. “Hands up,” said one in English. The four were now prisoners of war, and Gertrude Legendre had just become the first American woman in uniform captured by the Nazis

Finn is The Washington Post’s national security editor. This article is adapted from his book, “A Guest of the Reich: The Story of American Heiress Gertrude Legendre’s Dramatic Captivity and Escape From Nazi Germany,” published by Pantheon Books.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments