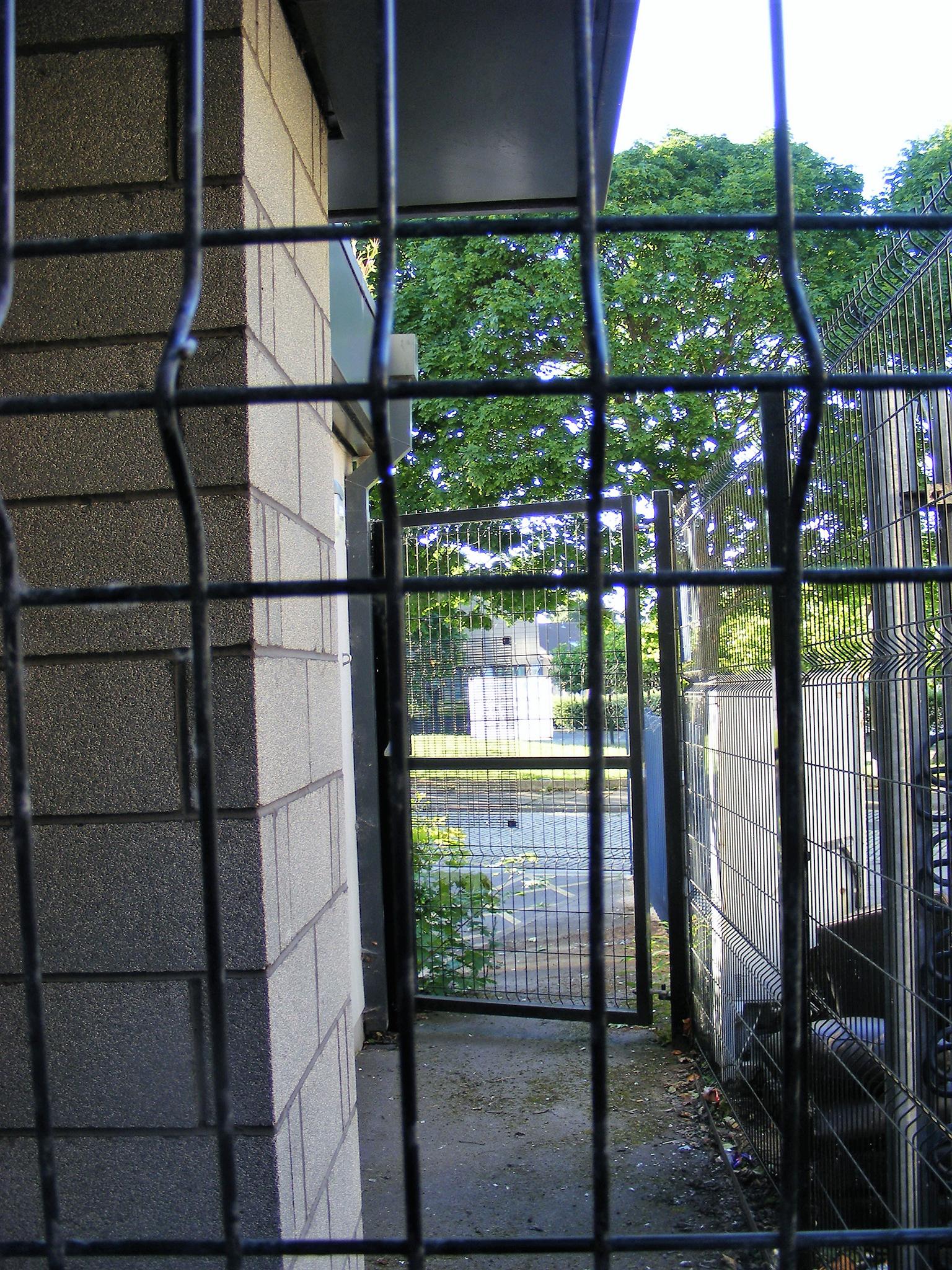

Grim and proper: Why so many school look like prisons

Turning places of learning into fortresses does not protect pupils from the shortfalls of the very security fencing is supposed to provide

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For more than 20 years state schools, academies and free schools have been surrounded by high and forbidding fences: first around their buildings and hard-surface playgrounds, later around outbuildings and playing fields (should they be fortunate enough not to have sold these off for housing).

Why such drastic measures when the most pupils are guilty of is pretending the dog ate their homework? In truth the prison bars on windows, fortified entrances, high-wire fences and ever-vigilant CCTV cameras at education institutions are directly the result of Government policy – namely listed in a 1996 Department for Education & Employment report titled “Improving Security in Schools”.

It is argued – here and in other health, safety, welfare, and equality, legislation – that security in schools is essential for safeguarding pupils from perceived threat presented by trespassers, intruders, rough-sleepers, thieves, graffiti artists, vandals and arsonists.

Arsonists – never discounting past and present pupils with a grievance, grudge, abandon or love of fire – present by far the greatest threat in terms of potential, irreparable damage. Comprehensive schools – Garibaldi in Mansfield, St Felix in Newmarket among them – are known to have gone up in flames. And much more common “incidental” school fires occur an astonishing 1,500 times each year.

Off premises, dog-walkers and their dogs also pose specific problems, as do angry parents and pickpockets. Pupils need to be protected from the likes of Peeping Toms, enraged relatives, paedophiles, bullies, drug dealers, drug runners, and robbers.

Paedophiles give rise to the most contentious discussions around enhanced school security. Children are given the message “Beware of strangers!” but how does that protect pupils from the more insidious, persistent and entrenched sexual abuse perpetrated by the likes of relatives and opportunists who are not impacted by school security? Even if children are protected from meeting paedophiles or drug handlers over the course of the school day, might they not still remain vulnerable to being groomed, enticed, or paid off during the evenings, weekends or holidays?

Conversely how do we stop school children leaving the premises? There are many pupils who bunk off lessons they don't like such as maths or games, or perhaps for half a day, or who leave to go and tease the fish-and-chip-shop owner down the road. Nevertheless, parents and teachers seem to be reassured by the exits, swipe cards, electronic bracelets, and sentries that can catch truants returning.

After a thorough risk assessment, school governors, managers, head-teachers and bursars must decide what fencing to order, and when.

The heights of fences and gating seem dauntingly high: one fencing contractor recommends 3- to 3.5-metre-hight protection in the inner city. Metals used include powder-coated palisade, weld mesh, paladin, or vertical spiked bar and some of the more detailed specifications of materials for schools are not too different from what the Home Office prescribes for prison estate and immigration-control centres.

All fencing must have somewhere to allow cars, staff, pupils and visitors to enter and exit: remote-controlled gates or turnstiles must be robust. But this raises a crucial safety issue. Since 2010 it is estimated that up to 12 children have been trapped between closing gates fitted in private homes, factories and offices and schools, and two children have died of the compression (though relevant statistics are hard to come by).

Even if all safety precautions, planning permissions and building-control officer standards are adhered to, there still remains the issue of how a community views a school in its midst that resembles a boot camp or detention centre? How do teachers feel turning up for work with only 40 seconds to enter the grounds before the gates swing shut behind them? And do the pupils themselves regard their schools and colleges as intimidating, incarcerating places?

Whenever I speak to young people who have been trusted to come and go as they please, they claim to be delighted not to be fenced in – many pupils will willingly sign in or sign out at reception or stay for detention if they are persistently late for registration without the need for harsh enforcement.

After all, scholars are not routinely confronted with prison bars when exercising in the park, watching football, bathing in the ocean, shopping in a mall, or when graduating from university. Indeed, universities can be veritable miniature garden cities. The bequeathed hillside acres on which so many universities are built must be a security officer’s nightmare, yet the reality suggests otherwise: that the benefits of freedom outweigh any threats presented because of it.

Then there are the aesthetics. What will impenetrable steel fencing look like in its urban or rural setting? People often imagine that if a road is not in a national park, ancient city, conservation area, nor housing a theatre, library or gallery of national importance, then it can be ignored.

Far from it – neighbourhoods still value appearance. There can be considerable pride in a local primary school – it is often the centre point of community for villages or suburbs that have long lost their post offices, pubs and local churches. Thus when any board, stakeholder or council erects barriers, that becomes deeply symbolic.

No authority better understands the dilemma of damaging the visual and expanding environment better than Nottinghamshire County Council, with its superb 2010 “Design guidance for perimeter fencing at schools” which leaves no stone or perspective unturned. If only this bigger picture perspective were taken into account beyond the Midlands.

Then there is cost – which is astronomical. W-headed, T- or X-headed, 78-inch palisade costs at least £44 per metre, plus an extra £100 (excluding VAT) per metre for bedding it in. Small infant schools spend tens of thousands of pounds for “complete” security; large comprehensives spend hundreds of thousands, and that is just the cost for installation – there is also the round-the-clock maintenance and repair costs involved for the upkeep of gates and constructed boundaries. Governors and local education authorities must also consider whether their money might better be spent on extra foot patrols, additional receptionists, more text books, school journeys, teaching assistants, more comfortable furniture, etc. And do they choose barbed wire, razor wire, or jagged glass set in concrete? School council or school counselling?

So we are left with a choice: view all passers-by as perverts, or potential collaborators? Opt for CCTV or interactive learning screens? Invest in the school council, or school counselling?

Twas ever thus: fine schools, top academies, and thriving higher education colleges are filled with the buzz of life in all its diversity, richness and asymmetry. Defensive institutions, on the other hand, simply deepen their moats and raise the drawbridge, hoping the big bad world outside makes no more advances. In Nottinghamshire’s words, it is surely time to “set parameters on perimeters”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments