Is WHSmith really the UK's worst shop?

After it was revealed a branch in a hospital was selling a tube of toothpaste for a whopping £8, the chain was voted the worst shop in the UK. But is it really? And are you a snob if you think that?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Poor old WHSmith. For the eighth year running it is propping up the annual league table from consumer magazine Which? as the worst retailer on the high street, as voted for by consumers.

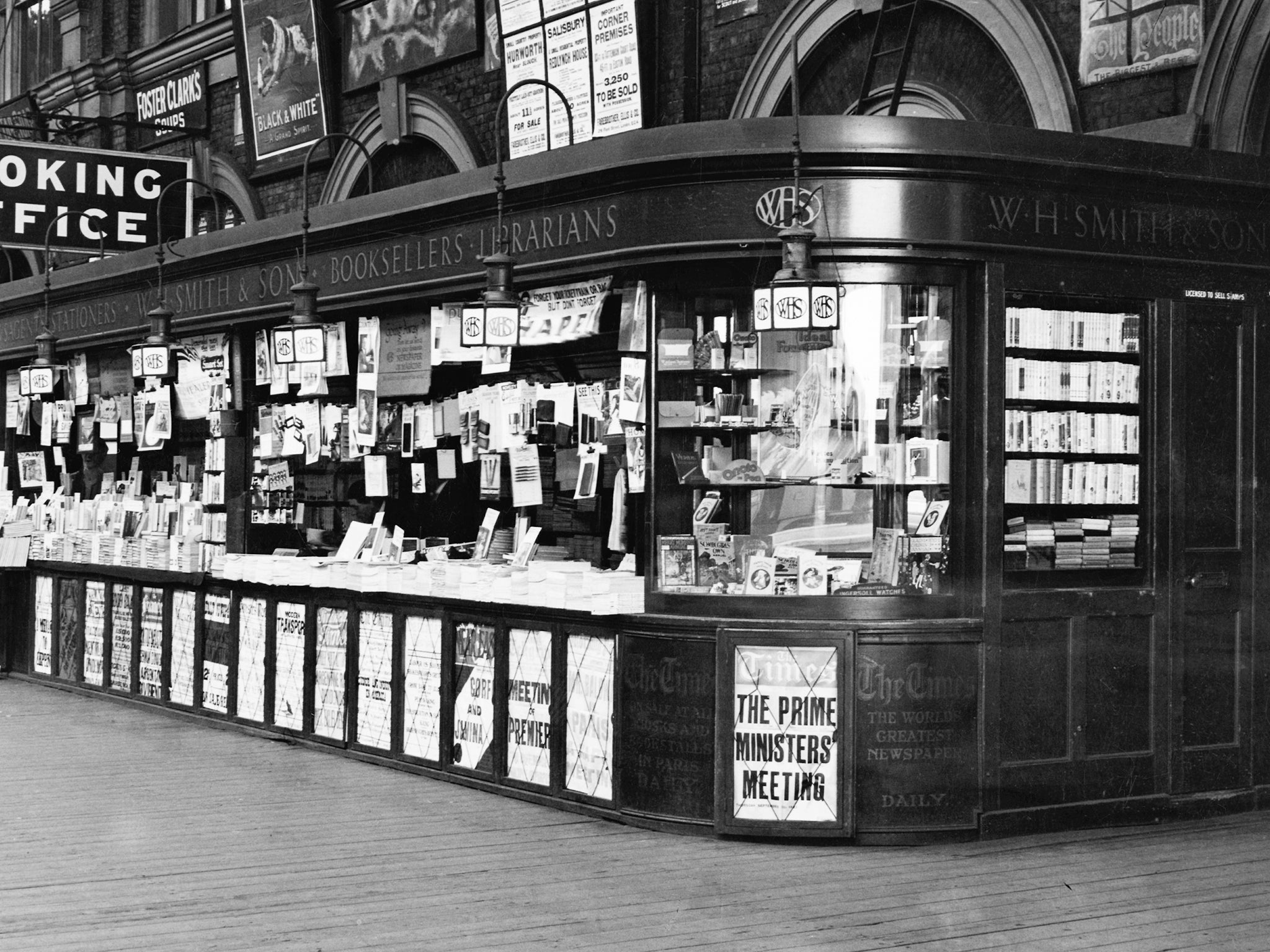

The venerable chain – it was founded 226 years ago – is these days a bit like the shopping equivalent of going to the dentist. It can be a painful experience trying to find what you want, it can be shockingly expensive, but sometimes you have no other option but to go.

Even before it (perhaps inevitably, given its past performance) got a roasting in the Which? survey, WHSmith was in hot water for its pricing tactics at hospitals.

Earlier in May it was noted that the shop’s outlet in Pinderfields Hospital in Wakefield was selling a small 75ml tube of toothpaste for a whopping £7.99 – the same item was on sale in a nearby Tesco for just 80p.

WHSmith blamed a pricing error, but anyone who’s frequented the store will know that there’s a certain duality at play here… some things are ridiculously cheap, others are astonishingly expensive.

Its pricing system seems to exist in a dimension all its own, like the nightmarish Upside Down from Stranger Things. Smokers will have considered giving up their habit on the spot when faced with the tobacco prices, which is perhaps no bad thing on public health terms. And yet, how many times have you been in to buy, say, a packet of chewing gum and been mesmerised by the offers of a barrel of spring water or a slab of chocolate the size of an internal door, yours for a pound if you purchase a newspaper that you’ve never considered reading in your life.

In fact, the Upside Down analogy is pertinent for anyone who ventures through the doors of WHSmith. What even is this shop? What do they sell? What do they want me to buy? A magazine? A bestseller? A protractor and set square? The biggest box of coloured Sharpie pens available to humanity? Board games, chocolate, huge, unwieldy books about gardening and Star Wars vehicles?

The shops seem designed to confuse and confound. We stand there in the street, weighed down with bottles of water we didn’t want, a perplexing copy of The Daily Telegraph, and a Monopoly: Game of Thrones Edition, scrutinising our receipt and wondering where the money has gone and why we never got that chewing gum we went in for.

WHSmith is often the shop of last resort, that oasis in the train station or airport, the place where we can pick up those things we forgot, or suddenly need, or never knew we wanted. It is the shop we love to hate, or maybe that should be hate to love.

According to more than 1,000 people surveyed by Which? in January, respondents found WHSmith to be out-dated, selling expensive products, and employing rude staff.

One area in which WHSmith draws particular ire is its role as a bookseller. Aside from a shelf of discounted new releases near the entrance, the books often take some finding. Take a left after the cuddly toys, sharp right by the printer ink, past the fluffy pencil cases, and straight on ‘til morning.

A little over a year ago Waterstones chief executive James Daunt had a pop at WHSmith for its “godawful uniformity” and “crushing consistency”. WHSmith used to own Waterstones, between 1993 and 1998; Daunt was speaking at a media conference where he was championing Waterstones policy of empowering booksellers with autonomy and announcing the opening of unbranded Waterstones stores in towns such as Rye in a bid to combat the homogeneity of the high street.

Anyone serious about their books has to agree; in the absence of an independent bookseller to support, if it comes down to a choice between WHSmith and Waterstones, it’ll be Waterstones every time.

And there lies the rub, and it took several authors this week, chief among them Joanne Harris, to point out an uncomfortable truth: are we all hating on WHSmith because we’re, well, just a teeny bit snobbish?

Harris, author of Chocolat and her latest, The Testament of Loki, opened something of a can of worms when she said on Twitter, “While it may not be the coolest shop on the high street, research suggests that WHSmith, and not Waterstones, is the place where most working class people buy books. If we care at all about promoting literacy, we should at least be aware of this.”

As the replies to her post mounted up into the hundreds, Harris added, “All the replies from well-meaning middle class people saying, ‘Yes, but it needs to stop selling cheap chocolate and tat’ may have missed my point. Some people may like cheap chocolate. They may like the fact that WHSmith provides a non-threatening, familiar environment.

“Research strongly suggests that readers from certain backgrounds are less likely to go into Waterstones because it looks expensive and intimidating to them. WHSmith, with its ‘cheap chocolate and tat’, looks more welcoming. They buy their books there instead.”

Her thoughts were backed up by publisher Scott Pack, who used to work at Waterstones, and tweeted, “We did research into this and it was clear that many Smiths customers found us, and other ‘serious’ bookshops, intimidating.

“Some of these people read a book a week (!) but as it was crime or romance they felt they would be looked down on by booksellers.”

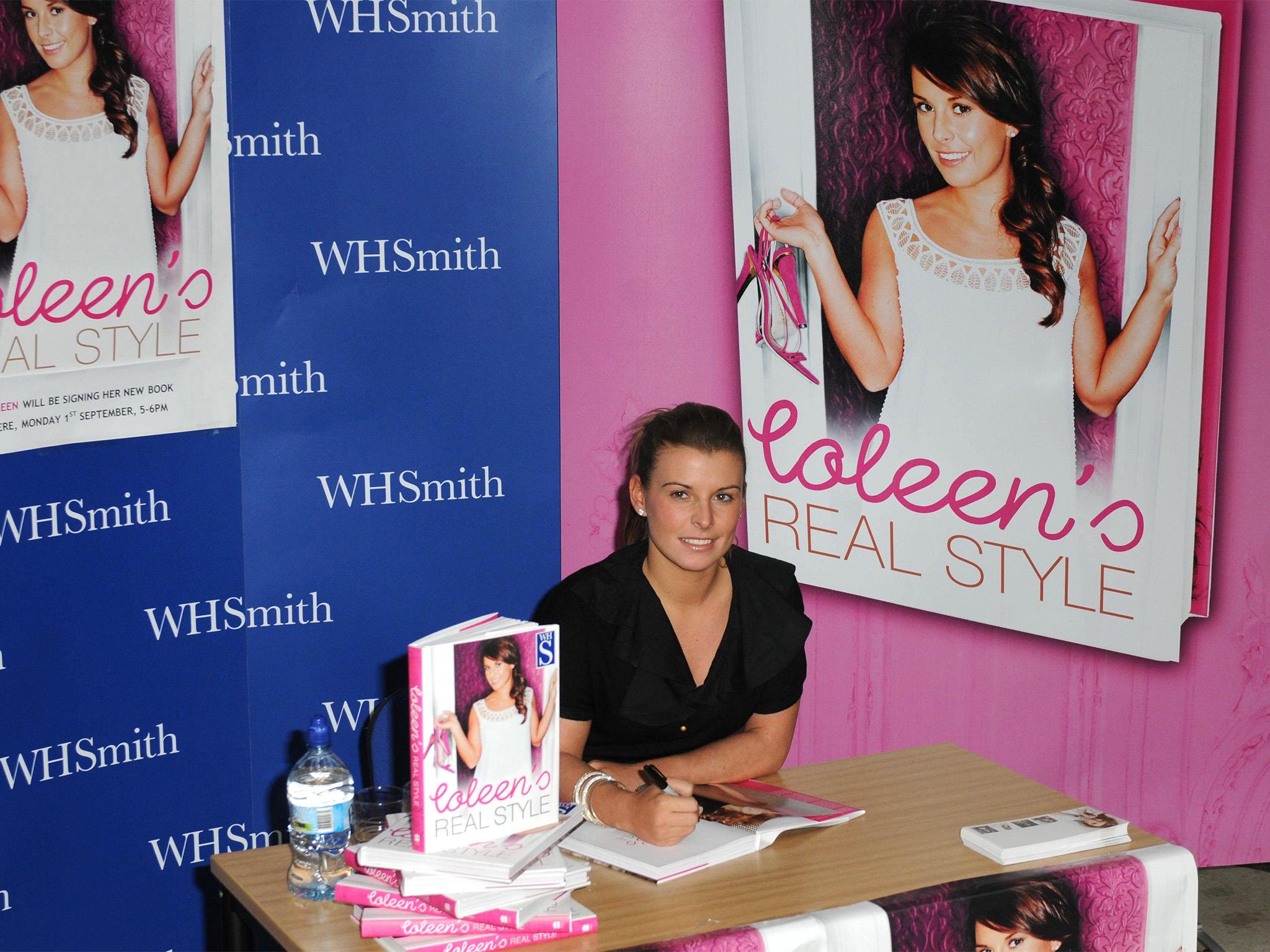

The replies to Harris, many along the lines of, “Yes, they sell books but only crappy celebrity autobiographies”, did indeed begin to resemble something along the lines of slight snobbishness. Yes, WHSmith might cater to the working class as much as Greggs and Wetherspoons does. Yes, it might be the place to pop in to for fags, mags and boiled sweet bags. But there are books there, if you care to look. Sometimes they’re at the back, sometimes they’re on a different floor. But they are there, and generally lots of them.

Indeed, as if by perfect timing, on Wednesday WHSmith unveiled the return of its Thumping Good Read Awards, which has Peter James and Jojo Moyes lined up as judges of the seven chosen titles that are up for the £10,000 prize.

It’s 15 years since the chain last ran the awards, and Moyes – author of Me Before You, who recently stepped in to save the adult literacy scheme Quick Reads from closure with her own money – said, “In a relentless, digital age many people are starting to understand that to get lost in a thumping good read is not just pleasurable but also far better for us than endlessly scrolling down a screen.”

Peter James added, “The Thumping Good Read is something I’ve always considered to be unique among all literary awards for what it celebrates, and that is the unalloyed joy and exhilaration of the page turner.”

So isn’t it perhaps time we stopped hating on WHSmith so much? There are few companies that have lasted so long, after all. It’s perhaps true that when Henry Walton Smith and his wife Anna established their news vendor business in Little Grosvenor Street, London, in 1792, they could never have envisaged a shop on every high street with self-service tills and Lotto machines. But the odds are, they’d have been proud of what their business became, not just the diversification but the fact that they were not only selling books by the truckload but promoting reading through awards.

It may be true that if you’re looking for the latest slim volume of existential literary angst reviewed in the London Review of Books, WHSmith might not be your first port of call. But if, like most readers, you want to find out what’s in the top 100 bestsellers or get your hands on the newest science fiction, thriller or romance novel, then why not?

WHSmith has learned over the centuries – centuries – that you must adapt to survive, and that’s precisely what it’s done. If we’re being sniffy about it, and looking down on the people who shop there, then we might as well be telling people that their reading habits aren’t worth a damn unless they buy their books from a shop with a suitably literary air. And that, as Joanne Harris and others have pointed out, is just pure snobbishness.

Yes, WHSmith is like a chaotic other dimension, a riotous mix of felt-tip pens and fruit bon-bons and magazines-with-DVDs about the Battle of the Bulge. But so what? It is what it is, and if it feeds the need for reading to a swathe of people who find other places intimidating or “not for them”, then it’s filling a much-needed role on our high street.

In fact, I might just head down there now. I have a hankering to buy Harris’s new book, and with a bit of luck I might get a Galaxy bar the size of a mattress into the bargain.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments