Money for nothing? How we broke the welfare state – and how we can fix it

It is nearly eight decades since the introduction of the welfare state but, as Hannah Fearn explains, today’s system is unrecognisable from the one envisaged by William Beveridge in 1942. And it is, clearly, no longer fit for purpose

So ingrained in the collective psyche is the concept of the welfare state, it is remarkable to remember that it is still less than 80 years old. Like the NHS, which sits at the centre of our great British social contract, we speak of it as a great unmoveable: almost everyone agrees that we need a welfare state, even if we don’t agree on how it should operate and on who should be its greatest beneficiaries.

And yet the welfare state as we once knew it is crumbling. Universal credit, the Conservative government’s reform of the system, is a story of failure upon failure resulting in dramatic stories of neglect – and, in a handful of shocking examples, even death.

Astonishingly, the work and pensions secretary, Amber Rudd, last month admitted that it is the welfare state – created to prevent hunger and destitution – that is now actively causing it, with the shortcomings of universal credit responsible for driving up the number of Britons who are reliant on food banks to feed their families.

So how did we get here, and is there anything we can do to save our welfare state?

* * *

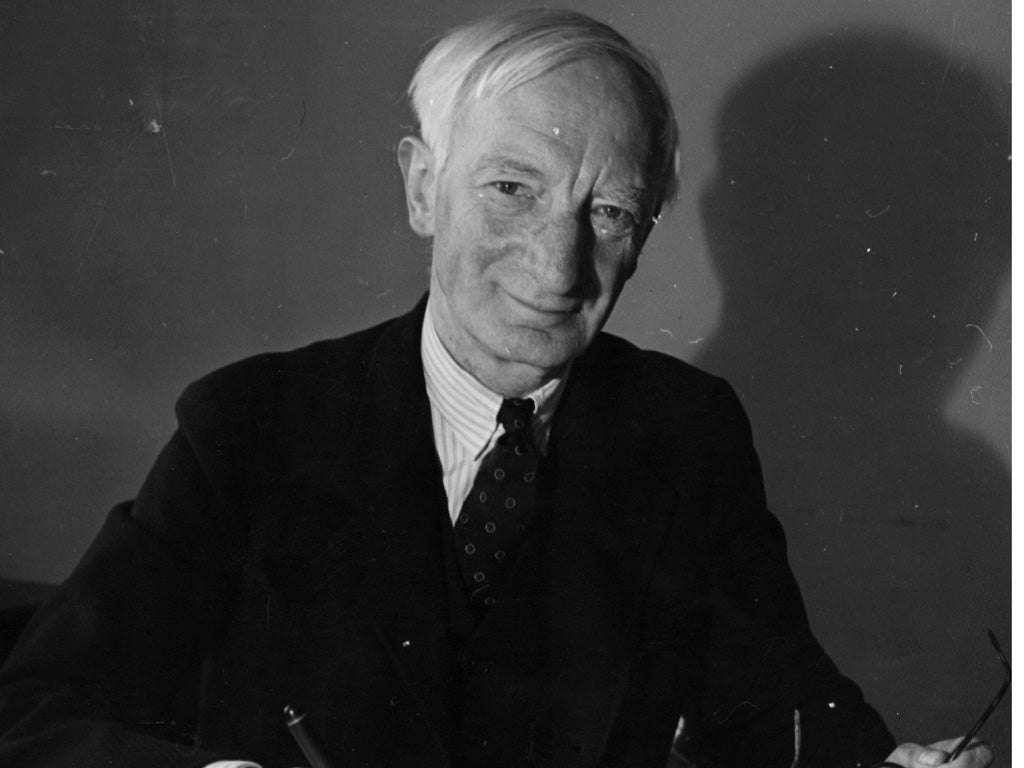

The roots of the welfare state as we know it today lay in a lengthy government-commissioned inquiry into social security. The resulting 1942 Beveridge report was an unlikely hit among policy reviews, if you can imagine such a thing. Somehow, its author, William Beveridge, managed to capture a post-war zeitgeist (a longing perhaps), even while wartime fighting continued, penning an emotive series of recommendation that spoke to the spirit of the nation. Politicians on all sides of the house were listening.

Beveridge identified what he called the five “giant evils” of British society: want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness.

“The state should offer security for service and contribution,” Beveridge wrote. “The state, in organising security, should not stifle incentive, opportunity, responsibility; in establishing a national minimum, it should leave room and encouragement for voluntary action by each individual to provide more than the minimum for himself and his family.”

After the election of Clement Atlee’s Labour government in 1945, Beveridge’s recommendations were turned into political action: a network of public services and financial safety nets for the unemployed, the disabled and the ill; guarantees of education and (the hoped for, if not the realisation of) equal life chances for children; the promise of decent, affordable housing and, through all this, a commitment to the redistribution of opportunity. These public services were free at the point of use and, in most cases, universal.

The philosophical and political ambition of this move cannot be underestimated. Yet what seemed radical then, even future-proof, has visibly unravelled eight decades later. Two recent cases illustrate the point.

Stephen Smith was denied disability benefits and judged fit to find work by the Department for Work and Pensions when his weight had dropped to under six stone and he was unable to walk. An image of his naked, emaciated torso visibly captured the failings of the means-testing system that now dogs the benefits system. He later received an apology, but his story is by no means isolated.

Meanwhile, in February, Jeff Hayward finally won an appeal against the judgement that he was fit for work – seven months after his death from a heart attack.

The Ken Loach film I, Daniel Blake is fiction only insofar as the characters are drawn from the imaginings of that celebrated cinematic realist; their stories, their experiences as “clients” (not citizens) of the welfare system are taken directly from the lives of the thousands struggling to survive in a country where the promise of lifelong support, from cradle to grave, amounts to very little.

Given this backdrop, perhaps it should not be a surprise that public support for the welfare state has dissipated, particularly in the past three decades.

In 1989, 61 per cent of people polled by the British Social Attitudes survey agreed with spending more on welfare benefits for the poor. That fell to 27 per cent in 2009 and remained low (rising slightly to 30 per cent in 2014). In those later years, support for increasing taxes as a mechanism to spend more public money on health, education and social benefits fell particularly rapidly: 63 per cent supported that proposition in 2002, but that had halved to 32 per cent by 2010.

And despite vast expenditure – £264bn in 2017, accounting for 34 per cent of all government spending, and that’s before we add in the cost of the NHS – those five “giant evils” are still with us today.

We may describe them differently – we now use terms like poverty, chronic ill health, lack of education or skills, unfit housing and homelessness and unemployment – but they linger on.

* * *

The pattern of the welfare state’s disintegration began very early on, with the introduction of charges for dentistry and optician services in 1951 and prescriptions a year later. In 1959, the National Insurance Act introduced an earnings-related pension – a significant ideological departure from the flat rate contribution and pension payout that Beveridge had first envisaged in his report. From the first decade of its life, means-testing and contingency had entered the welfare state payment system. This small ideological tweak was enough to start a slow unravelling towards what could be its ultimate end: the failure of universal credit in 2019.

By the 1970s, Britain had built a nation of “homes fit for heroes”, vast estates of new council-owned homes that anyone could apply to rent. There was no stigma attached, at this time, to renting or to council ownership. Affordable housing fit to live in was considered a citizen’s right – one of the great early successes of the system.

A decade later, Margaret Thatcher’s Right to Buy did its dirty work, removing houses from state ownership and, with it, access to them for the poorest people. When the welfare state was born, private landlords were considered incapable of providing the good-quality housing needed to prevent the “squalor” that had held British society back. Yet Right to Buy created a powerful and unregulated market in low-cost housing.

By the middle of the 1990s, private landlords were forced to become the “solution” to our housing needs once again. And housing benefit – as Sir George Young then instructed – “took the strain” of that cost. The overall benefits bill rose and the changes meant more and more people who encountered the benefits system were now having to prove their eligibility for support.

Until this time the idea of universalism had generally been preserved. There were still unemployment grants available for those seeking creative careers, for example; nobody questioned the need for child benefit to be paid to every child, even though the payment stopped rising in line with inflation in 1990, in an early attempt to cut costs.

That feels unthinkable today. Why?

The introduction of means-testing in respect of most benefits altered how the public thought about the welfare state. Citizens now had to prove they really needed support; it was no longer a simple conditional right of their citizenship.

National insurance payments, which everyone duly paid, were not contributions to a national safety net but became regarded as a sort of government-sponsored pensions savings scheme. Today, the vast bulk of the government’s welfare bill consists of pension contributions, and yet if you ask the woman at a Clapham bus stop what she thinks it is spent on she will probably say either unemployment benefit or disability benefit.

As the state rolled back, and fewer individuals qualified for financial support, their views of the welfare state began to shift too. The concept of a deserving and undeserving poor became prominent once again, slowly spreading its tentacles through the entire welfare state system, even as it was still being established.

By the 1990s Britain faced a rapid increase in relative poverty as unemployment and sickness benefits were cut, no longer meeting the basic cost of living.

In his controversial Back to Basics election campaign, John Major spoke of the importance of “accepting responsibility for yourself and your family and not shuffling off on other people and the state”. Yet, arguably, welfare payments at that time also included mortgage tax relief – the ultimate reward for the “deserving” citizen.

Ask most liberal-minded people which politician destroyed the welfare state and they will either point to Margaret Thatcher, who lost the nation’s public housing stock and forced thousands of redundant miners to see out the rest of their working lives “on the dole” or “on the sick”, or to John Major and his Conservative moralism, which focused on the nuclear family as the protector of the British people, not the government and certainly not the “bloated” arms of government that allocated benefits and provided public services.

But really it was Tony Blair who drove in the final nails and sealed the fate of the welfare state as we now know it.

After Labour’s landslide election win in 1997, as the sell-off of social housing continued apace but employment prospects improved, Blair’s government became obsessed with the “responsibilities” of its citizens – the deserving and undeserving poor were resurfacing once again. A raft of politics which focused on punishment and reward were introduced. The best remembered of these initiatives was the introduction of anti-social behaviour orders, the use of which began to criminalise the ordinary, boundary-pushing behaviour of young people – particularly those from poor backgrounds.

This attitude infected almost all public services. Housing associations, for example, began offering complex reward systems which in the most extreme circumstances gave tenants money off their rent for behaving in desirable ways, such as paying their rent on time. It was a process of infantilising.

We have ended up with a system that is effectively a game of cat-and-mouse in which a claimant must end up near destitute to qualify for support

Public opinion started to shift too. In 1999, Blair delivered his famous speech about the welfare state, in which he claimed that benefits should always be a “hand up, not a hand out.” He spoke of ending fraud and abuse of the system; of focusing help on those individuals and families who needed it most. It proved a bellweather moment.

According to the British Social Attitudes Survey, the speech market a “point of intersection”, after which the trust of the British people in the benefits system rapidly eroded. Until this point, the public generally believed that the welfare state was partly to blame for causing poverty, with the levels of support offered set too low. Afterwards, the idea of the “benefit scrounger” began to emerge; the view that benefits were too lavish, allowing people to live very comfortable lifestyles without being required to find work, became prevalent. Support for the welfare state declined rapidly across all groups, but particularly among Labour voters.

Blair’s 1999 speech was far more complex (and progressive) than the soundbite it was remembered for: he was ultimately seeking to pave a new “road to a popular welfare state”. But his delivery had the opposite effect in terms of public attitudes. When he talked of focusing help on specific groups, people no longer felt that the welfare state was for them. And they no longer wished to defend it – especially in a period of relative national affluence.

As the researchers found, “support for the welfare state among Labour voters has been in steep decline for two decades. In 1987, around 73 per cent of the party’s supporters agreed that the government should spend more on welfare benefits for poor families, compared with just 36 per cent in 2011”.

Therefore, the creation of universal credit by the Conservatives in more recent years is not the source of the welfare state’s undoing, but a reaction to attitudes that had already set in motion a dangerous race to the bottom.

The result? Not a system, as was initially designed, intelligent enough to map a person’s path in and out of work and provide up to date support depending on their exact economic circumstances, but a game of cat-and-mouse in which a claimant must end up near destitute to qualify for support – and then wait five weeks, often resorting to food banks, to actually obtain the financial help they have been told, at the last, they deserve.

The loss of public belief in welfare hinges on the re-emergence of the idea of the deserving and undeserving poor – a concept that the original welfare state was designed to help eradicate. To prove oneself deserving, a claimant must jump through endless hoops and administrative tasks to demonstrate their fitness – whether for work, for financial support, for housing, even for medical care under an increasingly stretched NHS.

This burden of proof puts the new claimant immediately in dispute with the state – or, worse, as in most cases, in dispute with a private company acting on behalf of the state with targets set to reduce the number of claimants considered to be “deserving” in the first place. This is particularly distressing when it involves the assessment of claims based on ill health or disability.

How this feels to the claimant, as well as wider society, really matters. It has a huge effect on the results of the system. Hopelessness, anger and fear simply do not create the psychological conditions for human flourishing – or, to put it in less philosophical terms, the kind of stable mental health that leads to good employment opportunities.

Thus the welfare state is now failing on both sides: claimants are unhappy with the way the universal credit system treats them, feeling the promises made to them by the state are not kept; yet the wider electorate also feels short-changed. Nobody feels the benefit. The only way to save the welfare state from total disintegration is to reset it from scratch.

How do we do that? The answer lies in the early roots of welfare, way beyond Beveridge, to the Georgist idea of the “citizen’s dividend”.

* * *

Thomas Paine’s 1797 essay “Agrarian Justice” set out one of the first proposals for a social security system as we now understand it, but its principles differ significantly to those that underpin the welfare state we eventually got. He saw the earth, and the agrarian economy which man had built upon it, as a collective inheritance in which all people shared – and from which all people should benefit.

As he put it: “Men did not make the earth. It is the value of the improvements only, and not the earth itself, that is individual property. Every proprietor owes to the community a ground rent for the land which he holds.”

He was making the argument for a citizen’s dividend, payable by those who held the wealth at that time, to all those who were entitled to benefit from a shared resource. That is, everybody.

Even today, despite the complex political legacy of the past century, there is still huge public backing for the concept of universality in our welfare state. The NHS receives greater support than any other tenet of our state support system. Likewise, very few ever dispute the need to continue paying out an old age pension to those past the age of qualification (though this, of course, has risen in line with rising life expectancy and improved health in later life).

Where we believe it to be fair and to be right, the public agrees we should all share in a universal benefit. And the largest chunk of our shared welfare spending already falls into this category (ie on pensions). So, if this is the point of agreement, then this is the point from which the welfare state must be rebuilt.

* * *

The idea behind universal credit – removing the sense of infantilisation from the system, and paying claimants a single sum, once a month, similar to a salary – is a good one. In theory, it empowers those on benefits to live a more productive life. But in practice it has patently failed. So, what if there was a fairer, an easier and more psychologically beneficial way to achieve the same thing?

The argument for the universal basic income – a very old political idea that is receiving new interest across the globe as western economies battle to find new answers to the thorny question of welfare and poverty – is very simple. Pay all your citizens a dividend to recognise their participation in, and contribution to, the shared economy, and thus afford them a very basic financial security. From this point, economies flourish.

Emotionally freed as they longer having to fight to prove themselves worthy of social security, released too from the worry of how the family will be fed, citizens are free to pursue employment, self-employment, study, care duties, self-improvement and so on. Businesses have the confidence to start and grow; families can plan for their futures with some sense of security; care work – the bedrock of our economy, and almost always utterly neglected in mainstream economic calculations – is in itself rewarded financially.

It is intellectually challenging, in our current political climate, because it asks us to accept the idea of “something for nothing”, when our own welfare state, with the introduction of national insurance, was predicated on the opposite tenet of “something for something”. But the benefits system, not least the universal credit computer failure, is very costly, and endlessly complex.

Men did not make the earth. It is the value of the improvements only, and not the earth itself, that is individual property. Every proprietor owes to the community a ground rent for the land which he hold

By contrast, the payment of an unconditional sum as a right of citizenship – not a high figure, barely enough to get by and likely far below the current minimum wage – alongside the dismantling of the current welfare architecture is straightforward to explain, and simple to manage. Yes, it requires that we all pay more tax on what we do earn, but what we receive in return cannot be undervalued. The proposal, importantly, removes stigma from welfare: if we all receive the same, there is no difference between a student, someone navigating life with a disability, or a stay at home parent.

To pay for it, the expensive structures of the welfare state would be dismantled and those who earn on top of their universal income pay a much higher tax rate to fund it. There is no single accepted proposal around how much the payment should be if introduced in Britain, and how tax brackets would be shifted to accommodate that. It is a matter for heated debate.

In western Europe, the idea has recently been coopted by left-wing groups, including the Green Party and some parts of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party. Among ultra-left factions, it forms the core part of an idealised social structure known as “fully-automated luxury communism”. A book of that name setting out the proposal, authored by the Novara Media journalist Aaron Bastani, is forthcoming this summer.

However, the language around the proposition is problematic in terms of making it acceptable. The term “universal basic income” sounds both wonkish and overly-generous. Any serious proposition of the policy does not, in fact, provide the recipient with an “income” in the sense in which that term might be colloquially understood. At least in any major western democracy, the policy is not going to provide a liveable salary on which any individual or family could maintain a particularly enjoyable standard of life.

Indeed, it is not some fashionable wheeze dreamed up by the bearded and bespectacled of the alt-left in a coffee shop with a poured concrete floor in Peckham. Though labelled communistic, it is also supported today by many on the right who want to see the state take less of an interfering role in its citizens’ daily lives. The basic idea has been mooted in various forms by both the left and the right since the mid-1700s, with Paine’s essay perhaps its first crystallisation. Since then, interest in the concept of a payment to all citizens gained most traction amid the positivity of the interwar years, just two decades before the creation of the welfare state as we know it.

But a modern basic income – or “citizen’s dividend”, a more accurate term, and one I prefer – not only sounds different from those early proposals but feels different. It taps into the rights and responsibilities agenda that Blair introduced: we all have a right to profit from our economy, but we all have a responsibility to contribute.

Psychologically, it focuses on capacity and potential, not incapacity. It leaves space and time for development and enrichment. This is important. The current benefits system is experienced as a constant tail chasing, an anxious panic about the future, day by day, hour by hour. It does not leave time for creativity, for ideas, for learning, for experimentation – all necessary conditions for innovation and entrepreneurship.

A citizen’s dividend also promotes maternal feminism, which respects the critical role of attachment and the freedom to parent in the first two years of a child’s life. As it is paid to all, whatever their role inside or outside the home, it prevents control of wealth and financial power within families – a significant problem with the current benefits system, which still appoints one individual (often a man) as the head of a household.

Across Europe, governments have in recent years experimented with various forms of the citizen’s income, with varying results. The largest (though still relatively small scale) of these schemes concluded in Finland at the end of last year. The pilot was very specific: it selected 2,000 unemployed people and gave them a payment of €560 a month, which was not contingent on any means test or coercion into employment. Not enough to live on comfortably, but enough to afford some security.

The early findings scheme, reported last month, will be seized upon by those who are sceptical about the idea of gifting money for nothing. In the first year of the trial, payment did not help people move into work – in fact, it did not affect employment rates at all.

It did, however, increase wellbeing: those who received the income reported a greater sense of happiness and satisfaction. As discussed earlier, these psychological effects really matter, and are, over a longer term, economically significant.

By posting on social media we are sharing our likes and dislikes, our activities and behaviours – providing data from which large, powerful and often anonymous organisations can profit. Don’t citizens deserve a cut as a reward for their hard work?

A final study is expected next year and will look at the pilot’s wider outcomes, including the effects in its second year. It should be said, however, that this study is fundamentally limited as an assessment of how a citizen’s income should work – focusing only on the unemployed, and providing a relatively high individual reward.

Elsewhere (in Utrecht, Barcelona and a group of four Scottish cities), other schemes are trialling similar models of the policy. Each will report back on feasibility studies in the coming years. Critics and supporters will of course pick at them like a carcass; they will neither prove nor disprove the theory. What is needed is a grand experiment, and a government with the confidence to take the leap.

One way to think about the citizen’s dividend is as a reward for work already done; a chance to share in the nation’s business success, and address wealth gaps. In Alaska, a state which boasts significant oil wealth but little other major industry aside from fishing, citizens already benefit from a yearly, one-off payment based on the shared profits of the state’s oil companies. The Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend varies in size each year and is a bonus, not an “income”, but paid out more than $2,000 to each family in 2015.

As Beveridge originally envisaged, a citizen’s dividend like this offers some security in return for contribution. In Alaska, that’s a reward for forming part of the socio-ecoomic group that allows the oil companies to flourish and profit. But what could that contribution be in Britain today?

Even for those that appear economically inactive, each modern citizen’s contribution is constant, in the form of the silent stream of data that pours out of mobile phones, laptops, desktops and other digital devices. This data is now forming the bedrock of an information economy.

Look closely and there is, in fact, “something for something” in the citizen’s income. We each of us, in what we click, link, like and share, are doing unpaid and profitable work in our leisure hours. By posting on social media we are sharing our likes and dislikes, our activities and behaviours. Each of these small actions – done freely, by choice, and for our own enjoyment – nevertheless allows large, powerful and often anonymous organisations to profit. Those organisations are taxed, and our citizens deserve that money back as a reward for their hard work.

* * *

In 2017, work and pensions secretary David Guake gave a speech to commemorate 75 years since the Beveridge report. He recognised that the welfare state faced huge challenges, that its very survival was at stake, but he said that in order to continue to function it must “hold work at its head, while becoming ever more personalised”.

He was wrong. What is needed to save the welfare state is a recognition that in our society everyone contributes – whether through economic activity and employment, or through care work, or in other ways – and we all deserve to share in some of the rewards.

In our current political climate, where debate is increasingly polarised by the hard left and right, the universal basic income – or citizen’s dividend – is gaining popularity as it is being taken up by extremist factions. That is to all our detriment, because in fact there are a strong, mainstream liberal arguments in its favour: manifest in all the social, economic and psychological benefits it would bring.

Yes, the citizen’s dividend is expensive. But tax rises would be sufficient to cover a small regular payment. If the welfare state was based on a non-conditional payment as a right of citizenship, wages would rise as labour is in demand, inheritance tax hikes become morally and politically defensible and the introduction of wealth transfer taxes – the Robin Hood tax, as it is colloquially known – also becomes more palatable.

By failing to radically change the welfare state, the huge disruption of the labour market and the casualisation of the workforce we are already undergoing will continue. The Department for Work and Pensions is chasing to keep up, and in its constant attempts to revive universal credit it is fundamentally failing. No Labour government can come in and save the welfare state in its current form through magical thinking. What is needed is a major philosophical rethink.

In the case of pensions, we still accept universality in the welfare system. A citizen’s dividend is a natural, liberal extension of that principle.

Perhaps the first basic income payment would be nothing of the sort. Rather than replace the benefits system as it exists today, it would instead be an additional token payment, as made in Alaska, to ensure that every citizen felt they had, once again, a personal stake in the welfare state.

That alone would be worth it – but that is certainly not all it would achieve. It would be a first step in an economic revolution and a fundamental shift in our attitude to social responsibility – both long overdue.

It would not eliminate want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness. But it would remind us of our rights as citizens and our shared responsibility in helping to bring these to an end.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments