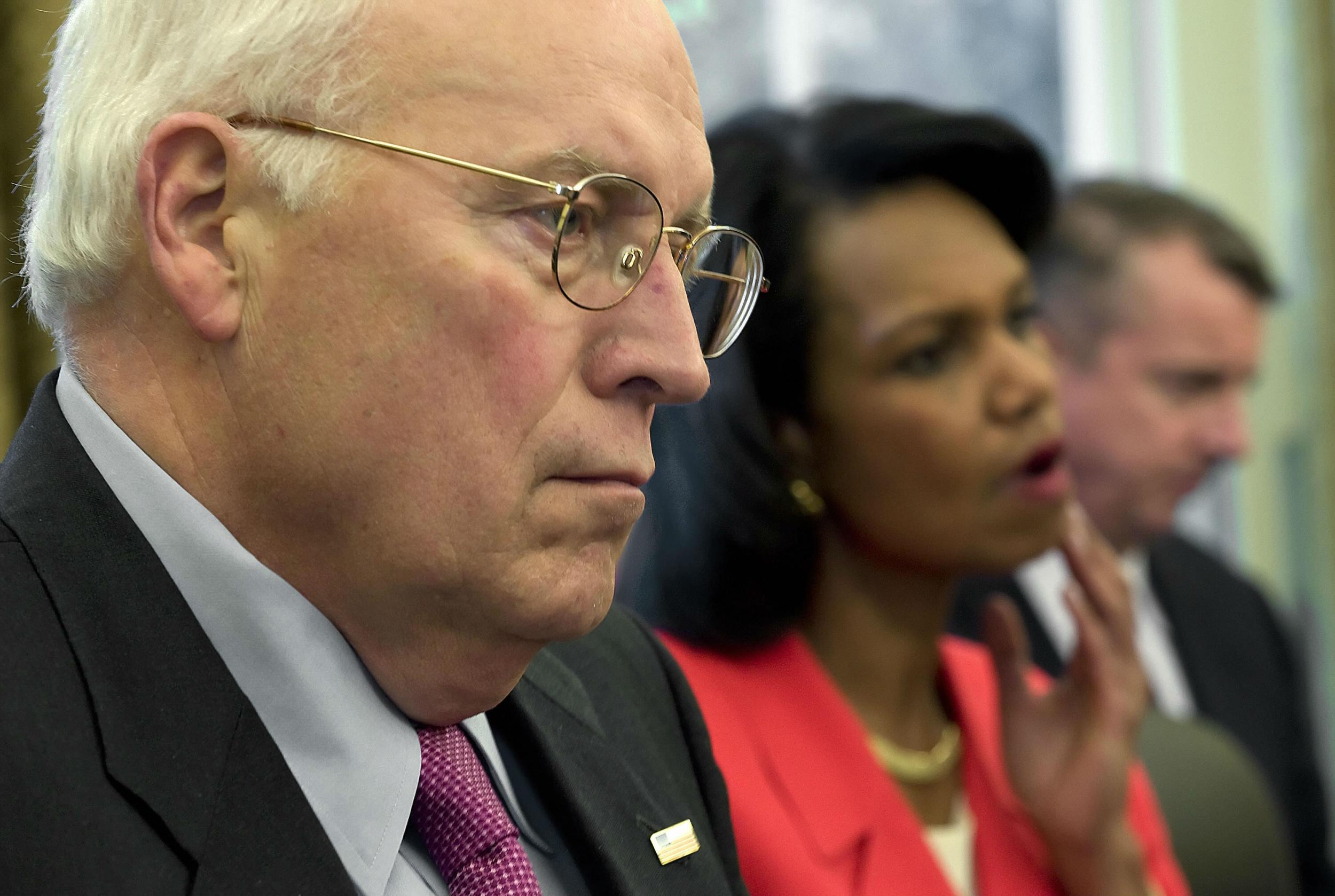

Vice doesn’t get it right – Dick Cheney was a much scarier vice president than that

The film has been nominated for eight Oscars and contains some fine performances – but there’s one crucial aspect of Cheney’s character that it fails to address, says Andrew Buncombe

There is a moment towards the beginning of Adam McKay’s film about Dick Cheney, where we see the vice president being grabbed by a secret service agent and bundled down to the depths of the White House. It is the morning of 11 September 2001, two hijacked planes have already struck New York, and amid the chaos it’s believed another captured flight is heading for “Crown”, codename for the White House. “Mr Vice President, we’ve got to leave now,” Cheney recalls agent Jimmy Scott telling him, in his 2011 book In My Time: A Personal and Political Memoir.

In the film, Vice, as in the book, we see Cheney quickly assuming charge. George W Bush has just been evacuated from an elementary school in Florida, and there are reports that several other planes may be heading to the nation’s capital. What are the military’s orders, Cheney is asked. Shoot them down, he responds.

That moment is perhaps the strongest in the movie, for it immediately links Cheney to events of that day and the so-called War on Terror that followed, something with which he will forever be associated. It may also be the moment in which the bulked up Christian Bale most effectively captures Cheney – gruff, resolute and menacing, the man who would become the most powerful vice president in history.

For if there is one overarching problem with McKay’s movie, which has been nominated for eight Oscars, more than any other film this year, is that its main subject is simply not scary enough.

Bale certainly tries hard. He may well deserve his nomination for Best Actor. But the slow, deliberate, heavy-set character he delivers is not the man who was nicknamed Darth Vader and considered it an honour. “I’ve been asked if that nickname bothers me, and the answer is, no. After all, Darth Vader is one of the nicer things I’ve been called recently,” Cheney told the Washington Institute in 2007.

Cheney became the running mate of Bush for a 2000 showdown with Al Gore and Joe Lieberman, a race that Gore was expected to win. Bush, inexperienced, lightweight and a former alcoholic – remember George HW Bush had always assumed Jeb Bush would follow him into the White House – needed somebody with experience. As a former presidential chief of staff, defence secretary and, at the time, the chief executive of the giant oil services corporation Halliburton, he had plenty of that.

In his memoir, Cheney claims he did not want the job and would merely vet a list of potential candidates, despite Bush’s appeal. “You know Dick, you’re the solution to my problem.” The movie suggests he was always keen for the job and played a shrewd hand. The events of 9/11 would be the trigger not just for the subsequent invasion of Afghanistan to drive out the Taliban from Kabul and mission to kill or capture Osama bin Laden. It also allowed those founders of the Project for the New American Century think tank – among them Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz and Cheney himself – to deliver on their long-held desire of ousting Saddam Hussein.

And it allowed those within the American state the cover they needed to behave in a manner hitherto avoided.

Five days after the attacks, Cheney was asked by Tim Russert how the government would respond to the terror attacks that killed about 3,000 people. The US military, he said, would of course have a role.

“We also have to work, though, sort of the dark side, if you will. We’ve got to spend time in the shadows in the intelligence world,” he said. “A lot of what needs to be done here will have to be done quietly, without any discussion, using sources and methods that are available to our intelligence agencies, if we’re going to be successful.”

Cheney already had a history of heart disease. But when he spoke that day, the Twin Towers and Pentagon still smouldering, the field at Shanksville littered with the debris of United Airlines Flight 93, you could almost imagine Cheney happily taking his place with the special forces or covert operatives, cutting throats, or snapping necks in a cave or CIA black site prison in Thailand. You could imagine him strapping a man down and waterboarding him, or else threatening him with a barking dog.

Darth Vader is one of the nicer things I’ve been called recently

“That’s the world these folks operate in,” he told Russert. “And so it’s going to be vital for us to use any means at our disposal, basically, to achieve our objective.”

It’s not that McKay’s film does not attempt to cover these issues, because it does. It focusses early on his career on his belief on unitary executive theory, the theory that president possesses the power to control the entire executive branch. With the help of lawyers David Addington and John Yoo, he helped develop the notion that anything a US president did was legal and lawful, especially in a time of war.

Likewise, what Rumsfeld and others in the Pentagon sometimes referred to as enhanced interrogation, could not be considered “torture” if the president had ordered it be carried out. Tellingly the index to In My Time, contains no references to torture, but it does to enhanced interrogation. He claimed that such interrogation of terror suspect Abu Zubaydah gave up information that helped lead to the capture of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the 9/11 ringleader.

“Despite the invaluable intelligence we were obtaining through the programme of enhanced interrogation, there was a move on Capitol Hill, lead by senator John McCain and Lindsey Graham, to end it,” he writes angrily.

Much of the problem is that Vice, like The Big Short which also stars Christian Bale and Steve Carell and is considered by McKay as a sister movie, is a “comedy-drama”, a genre of films that frequently fall between either camp. The presence of Will Ferrell as the film’s producer – McKay directed him in Anchorman, Talladega Nights and Step Brothers – pulsates through the movie.

“It was horrifyingly difficult. Some would call it foolhardy,” McKay told The National, of developing the script for Vice.

“The tone varies a lot more in Vice. There are times when it’s really dark and tragic, there are times where it’s very dramatic, and there are times where it gets very ridiculous, and I think those gear shifts were much more dramatic than in The Big Short.”

McKay is not the first director to have this problem with the challenge of styles. War Machine, written and directed by David Michôd, and starring and produced by Brad Pitt, is a 2017 satire, based on the Michael Hastings’ book about US general Stanley McChrystal. As with Vice, viewers were unsure whether to laugh, cry or simply become cynical.

This is a pity, for despite its major stylistic weakness, Vice contains some fine performances, by Amy Adams as Cheney’s ambitious machiavellian wife, Lynne, and Sam Rockwell, who presents us a pitch-perfect version of young Bush.

Most of the acting plaudits, have rightly gone to Bale. With the help of a reported 100 pieces of encapsulated silicone and the 40 pounds of extra weight that he put on, the star of Christopher Nolan’s Batman series walks, snarls and stares a lot like Cheney.

“There was an understanding that it would be an amalgam of Christian Bale and Dick Cheney, without covering his entire face,” Brian Wade, an artist who sculpted facial pieces for Vice, told The New York Times.

“The most successful makeups aren’t the ones where you’re trying to completely hide the actor.”

The final scenes in the film, in which Cheney is being interviewed and he defends the actions of the administration he partly led, echo the somewhat sour tone of the epilogue to In My Time, in which he criticises the incoming administration of Barack Obama and the decision to try to shutter Guantanamo Bay, and declare an end to torture.

In his account, Cheney rails at Obama for refusing to declassify documents he claimed showed the torture had provided actionable intelligence and only released those that suggested it did not. There was even talk of seeing to bring charges against those officials who had overseen the torture chamber.

“In the early days of the Obama administration, my first instinct was to let the criticism pass,” says Cheney, convincing nobody, as he details his trip to the national archives in Washington DC to take another look at the documents.

We settled on WMD, because it was the one reason everyone could agree on

“But the subject just kept coming up and the president and members of his administration were making assertions about the programme that were inaccurate.”

He adds: “I was appalled that the new administration would even consider punishing honorable public servants who had carried out the Bush administration’s lawful policies and kept the country safe.”

This is classic Cheney. He pushed the US and its allies to carry out an illegal invasion of a country based on intelligence – that Saddam possessed weapons of mass destruction – that was at best uncertain and piecemeal.

Some in the administration – Wolfowitz among them – admitted the purported threat of WMD was selected as the most politically convenient reason to sell the invasion to the American public. “For bureaucratic reasons we settled on one issue, weapons of mass destruction, because it was the one reason everyone could agree on,” he told Vanity Fair in May 2003.

More than 15 years later, the death toll of American troops in Iraq stands at 4,424, with at least 179 British soldiers killed, along with those from other coalition countries.

There have been several efforts to count the Iraqi dead, those from the fighting and the subsequent chaos and violence that was allowed to sweep the country. None has been entirely problem-free, but the toll must surely stand at more than 1 million.

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the militant who formed a precursor to Isis, was allowed to leave prison in 1999. He was not killed until 2006, by which time he was spearheading the insurgency against US and UK forces.

A full 18 years after invading Afghanistan, the US is still trying to broker a peace with the Taliban.

For all of this, Dick Cheney, now aged 77 and who followed up 2011’s In My Time four years later with Exceptional: Why the World Needs a Powerful America, appears to have no regrets. Even Bush, who signed off on the invasion, has turned to water colours and cycling sessions with wounded veterans, in what may be an attempt to reflect on what he did.

“I am a firm believer in America and its work in the world. Our political battles are messy, shrill and sometimes cruel, and yet for all of that, the system has a way of producing courageous and compassionate action when it is needed most,” writes Cheney.

“We have stood firm in the face of evil and defied history in the selfless way we have done it. Instead of seeking empire, we have sought freedom of others.”

It is this – the self-deception, the historical revisionism, the unceasing belief that everything he did served a higher purpose – that is the most terrifying aspect of his character. It is this that was impossible for any film to capture.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments