How the UK is exploiting its Covid vaccine donations programme for political gain

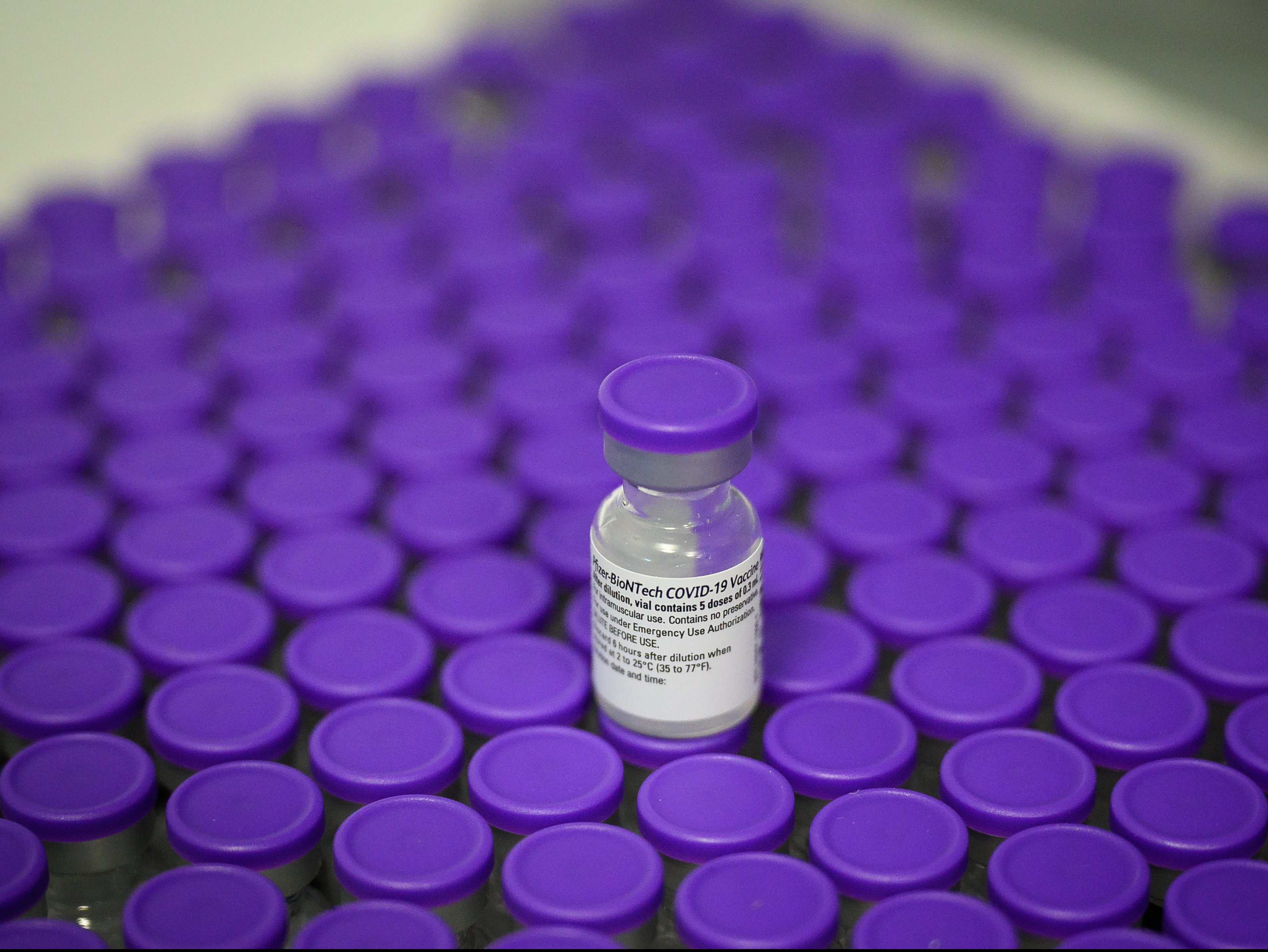

One of the clearest representations of the UK’s parochialism has been its accumulation and reluctant donation of Covid vaccines. Despite giving away 43 million doses – and promising to donate a further 57 million – Britain might use its surplus supplies to shrink its foreign aid budget. Samuel Lovett, Samuel Horti and Rosa Furneaux report

It was in the weeks before the G7 Summit, to be held by Britain in Cornwall, that the penny finally dropped among government officials. Covid was top of the agenda. World leaders would be meeting to discuss a global plan of action for tackling the pandemic. As hosts, the UK needed to be seen leading the way. “There was a classic kind of, ‘S***, what are we going to announce? We need to pretend we’re doing something’,” says a former Whitehall insider involved in discussions.

Cue the eventual announcement that the UK, having raced to procure its vast supply of doses to the detriment of the global south, would now be donating 100 million of its jabs. “In doing so, we will take a massive step towards beating this pandemic for good,” prime minister Boris Johnson said at the time.

Nearly nine months later, roughly 43 million surplus jabs have been shipped abroad. The clock is ticking. Despite its contributions to the surge in vaccine nationalism that underpinned the early western response to Covid, splitting the world into the protected and unprotected divide we see today, the UK has a long way to go in cleaning up the mess it helped to make.

As Britain’s politicians talk of “living with Covid” and declare that the fight is won, the pandemic continues to rage for those parts of the world where access to vaccination is limited or low. Data show that only 13 per cent of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose. In these nations, the spectre of disease, death and new variants looms large.

For much of the pandemic, the UK government has been gripped by a parochialism that has limited and curtailed the expression of goodwill to those nations and people crying out for help.

There are numerous examples to point to: in spring 2020, attempts among Whitehall officials to help Unicef set up PPE procurement systems were shut down over concerns that such efforts were aiding the “competition”; later in the year, it was announced billions were to be cut from the UK’s foreign aid budget; and throughout 2021, financial caps prevented Britain from donating tens of millions of masks and gloves to poorer nations. The list goes on.

However, one of the clearest indications of the UK’s inward-looking stance has been its accumulation and reluctant donation of Covid vaccines. Until the summer of 2021, the perception among Vaccine Task Force officials and ministers was “anything we can do to mitigate any risks [with the national rollout] is worth doing, even if it means that we’re kind of stepping back from what you might regard as a kind of international obligation to help provide surplus [vaccines],” the ex-Whitehall source said.

Dose sharing itself wasn’t necessarily always seen as a purely benevolent act but a means with which to strengthen diplomatic ties and shore up trade partnerships

This is despite the UK having had the strength of supply to begin donating doses to other countries months before it did. “If you look at the numbers, we almost certainly could have done something earlier.”

By January 2021, the UK, alongside Chile and Canada, had ordered the highest number of vaccine doses relative to its population, according to analysis. Each of these countries had procured enough supplies to administer at least four doses to every person. In contrast, the African Union and Latin American countries – with the exception of Brazil – had only secured enough vaccines to cover half their population with just one jab.

As the UK’s orders started to come through, mainly provided by AstraZeneca and then Pfizer, the noise emerging from Whitehall, both publicly and privately, was overwhelmingly positive: “We have the supplies. The rollout will proceed at pace.”

But although there was a recognition at the beginning of 2021 that the UK would ultimately need to share its excess doses at some stage, in the first six months of the year “the absolute kind of concrete line was ‘no’, because anything might jeopardise or slow down in some way the UK’s rollout,” the former government official said.

It was only by the summer, with the G7 summit in Cornwall on the horizon, that the reluctance to share doses “thawed” – largely due to the realisation that Britain needed to be seen to be playing its part in the global vaccination programme. Under the announcement made by the UK government, 80 per cent would go to Covax – the global vaccine-sharing initiative co-led by Gavi (the vaccine alliance) and the World Health Organisation, which has sought to procure and distribute supplies for the globe’s poorest nations. The remaining 20 per cent would be shared bilaterally with those countries deemed in need.

Even then, “dose sharing itself wasn’t necessarily always seen as a purely benevolent act”, but a means with which to strengthen diplomatic ties and shore up trade partnerships, the ex-Whitehall insider said. This meant overlooking countries that were more in need at the time.

When it came to those doses earmarked for bilateral donations, “there was a lot of talk about using them as kind of diplomatic leverage, prioritising countries with whom we had diplomatic or trade priorities.”

A list of countries to “target” with donations was drawn up by the FCDO. Commonwealth countries in the Caribbean were identified as options, as was Indonesia – “a big one that I remember standing out,” the source said. This pointed to the UK’s wider Indo-Pacific “tilt” and linked to the government’s attempts to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) as part of the wider reshaping of Britain’s post-Brexit trade relations.

There was “direct ministerial pressure” over the need to donate doses to Indonesia. This country, along with Kenya and Jamaica, was among the first nations to receive supplies from the UK, in July 2021. Alongside discussions of diplomacy, conversations were even had about selling doses with the aim of recouping costs, The Independent understands. However, nothing was ever operationalised.

Not one to miss a trick, though, the UK sought to ensure that, if it couldn’t sell its excess doses, it could still swap them with its rich western partners. In September 2021, it was announced that Australia had secured an extra 4 million doses of the Pfizer vaccine from the UK in a swap deal. At that stage, Britain had an excess of supplies and was nearing 80 per cent coverage of its over-16s.

Under the deal, Australia sent the same amount of doses back to the UK later in the year. Pointing to this very example, the former Whitehall source said the government “took those opportunities where we could have donated doses, but instead found a way to kind of bring the benefit back to ourselves”.

Not one to miss a trick, though, the UK sought to ensure that, if it couldn’t sell its excess doses, it could still swap them with its rich western partners

A government spokesperson said the doses swapped with Australia were not surplus to domestic requirements at the time.

For those 43 million doses that the UK has donated abroad, either bilaterally or through Covax, concerns have also been raised over their integrity. One report from last Autumn said that “a substantial chunk” of the nine million doses shipped overseas by the UK in August were due to expire in a matter of weeks.

Much of the west has been guilty of leaving it too late to send their excess supplies abroad. In January, the Africa Centres for Disease Control (CDC) said at least 2.8 million doses of jabs donated to African countries have expired, with the vaccines’ short shelf life given as the major reason. Internal analysis conducted by Gavi, and seen by The Independent, shows that vaccine doses donated by western governments via bilateral arrangements are, on average, 32 per cent closer to their expiry date than supplies procured through the Covax initiative.

Perhaps worse still, the UK and the wider west has wasted millions of doses that could have otherwise been redirected to the Global South. Last summer, Britain threw away more than 600,000 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine after the life-saving jabs were allowed to pass their expiry date, as first revealed by The Independent. Following a change in national vaccination policy, made in May, the jabs were deemed surplus to requirement. Yet rather than donate the vaccines abroad, they were eventually allowed to expire before being destroyed at the end of April 2021.

More recently, an NHS source told The Independent that general dose wastage worsened at the turn of the new year, after trusts ordered tens of millions of extra jabs in preparation for the UK’s booster drive, only for demand to drop off after Christmas. Around 2 million Pfizer doses were set to be thrown away at the end of February, the source said.

Wider analysis from the People’s Vaccine Alliance suggests that 55 million doses held in the European Union were due to expire at the end of February. Globally, 100 million unused jabs were in line to be destroyed last month, according to one WHO official.

Now that the UK has delivered its vaccine programme, more or less offering a jab to all those eligible for one, there is the question of what comes next with its vast supplies. There is a growing belief that Covid vaccinations will be required for certain groups at least once a year, as with flu, if not twice. Understandably, the government will need to maintain a steady flow of doses.

At the same time, the UK remains under pressure to honour its commitment to ship 100 million doses abroad, and is holding further conversations with western and global health officials about donating more in the year ahead. Except, following new international guidance that allows an elite group of 30 rich nations to report donations of excess vaccines as foreign aid, there is an expectation that the UK will now stand to make money off the supplies it gives away.

Analysis suggests that 55 million doses held in the European Union were due to expire at the end of February. Globally, 100 million unused jabs were in line to be destroyed last month

As revealed in a joint investigation by The Independent and The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, the UK could save at least £144m on foreign aid spending after the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) recommended that every vaccine dose donated by a country in 2021 counts £5.12 to their aid budget.

The overwhelming majority of vaccines donated by Britain have been AstraZeneca, which the government paid a reported £2.29 per dose for.

Oxfam International described the guidance, which even allows governments to count vaccine donations as aid if the jabs were never administered, as an “insult to the world’s poorest countries”. It said that the “unacceptably high” guideline price “leaves the door wide open to rich countries falsely inflating the true cost of donated doses”.

If the UK chooses to report its past and present vaccine donations as foreign aid, this will shrink the fiscal space dedicated to helping fund vital overseas projects, some of which are tackling malaria, poor water sanitation and neglected tropical diseases in the world’s poorest countries.

Some countries have already decided against following the OECD guidance. The Netherlands said that donated vaccines were “purchased and financed for vaccinating our own population and not for development aid purposes” adding that “relabelling” them as foreign aid could reduce a country’s other development spending.

Luxembourg said that it will not report excess donations as foreign aid, and it’s understood the same is true for the US – the largest vaccine donor in the world. But it remains unclear what path Britain will take. The Treasury has yet to make a final decision on whether the UK will count its donations as aid at £5.12 per dose.

Whitehall sources said officials were aware of the optics and how it would look for the government to be seen making money off its excess supplies. Criticism of Britain’s global health agenda and limited efforts in tackling vaccine inequity is “being factored in” to the Treasury’s decision-making regarding the OECD guidance, an HMT insider said.

“But then they’re also thinking about a bit more, or questions are being asked about what [the] implications” will be if the UK commits to £5.12 per dose, the source said, adding that any reduction in overall foreign spending would “make some people in the Treasury happy”.

Excessive purchases of doses in the context of limited global supply were directly responsible for denying access to these life-saving tools in developing countries

Understandably, the guidance has sparked outrage. In a joint statement coordinated in February by the European Network on Debt and Development, 35 civil society organisations that jointly monitor foreign aid policy-making called on donor countries to “completely abandon” plans to count donations of surplus vaccines towards foreign spending. (Eurodad receives funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which is a major funder of the Bureau’s global health team.)

“These intentions were unconscionable – these vaccine doses were never purchased in the interest of development partners and should not be counted as such,” they wrote. “Indeed, excess purchases of doses in a context of limited global supply were directly responsible for denying access to these life-saving tools in developing countries.”

Yet the UK may eventually chose not to listen. Indeed, as the OECD guidance is nothing more than a recommendation, and not set in stone, consideration is also being given to claiming back more than £5.12 per donated dose. This is due to concern that a commitment to the current price could set a “precedent” for future donations of more expensive vaccines.

Britain is reported to have purchased its supply of Pfizer vaccines at an initial price of £15 per dose. If the UK donates any of these doses in the future, and keeps to the OECD guidance, it could miss out on millions.

“It’s still kind of unknown what the final picture would be because … there could be some precedent setting and then next year you might find yourself donating more expensive vaccines, and with the $6.72 [£5.12] you might prefer if you actually use the actual amount [spent per dose],” the HMT insider said.

UK aid spending must by law reach 0.5 per cent of the country’s gross national income. The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) said that aid reporting for vaccine donations would be in addition to the 2021 aid budget, but that this would remain within the 0.5 per cent target because of the growth of national income forecasts.

Discussions are also ongoing whether any doses donated beyond the initial 100 million target set last year could also count towards foreign aid spending. “They’re still deciding,” the HMT source said.

Clearly, Britain has not showered itself in glory throughout this pandemic, at times adopting an agenda that – contrary to the recommendation of the science community’s best minds – has rejected global cooperation, prioritised domestic interests and forsaken the suffering of some of the world’s poorest and most neglected populations. In doing so, the UK can certainly argue it’s left the worse of its epidemic behind. Covid is no longer top of the agenda, as it was when Boris Johnson and his fellow G7 counterparts met in Cornwall last summer. There is now a desire, and, more importantly, an ability to look past this disease.

But the same cannot be said for many other parts of the world. Health leaders have repeatedly warned that this pandemic won’t be over until we’re all safe, and having failed to do more in helping the cause of others, Britain risks jeopardising much of the progress it has made – irrespective of through which means.

A government spokesperson said: “We have taken a leading role in ensuring developing countries can access vaccines. The majority of our donations were distributed by Covax, which allocated doses based purely on need – in line with their fair allocation model.

“We make no apologies for doing everything we could to ensure the swift and effective rollout of Covid-19 vaccines – over 140 million jabs have now been delivered across the UK, saving countless lives and allowing us to restoring people’s freedoms.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments