Hitler, tweets and Trump: What do they have in common?

The internet and social media would have fascinated the dictator, who was a fool for technology. So is the president. But it’s the anonymity of hatred that make online trolls and Nazis so comparable, writes Robert Fisk

Sefton Delmer used to be a hero of mine. As a cub reporter on the Sunday Express, I read this veteran Expressman’s account of interviewing Hitler in the burning Reichstag and running a “black” radio station for the Allies during the Second World War. I still have a letter from the great man – sent to me in 1969 after I’d written about his wartime work and sent him a bottle of champagne (paid for by Beaverbrook) for his help – in which he curses then TUC head Vic Feather for claiming that while Swedes and Germans respected the law, the British worker did not.

“A superb way to win confidence for this country,” Delmer scoffed to me. “Twice in my lifetime we went to war against the Germans because they insisted on tearing up scraps of paper. And here comes this bloody ignoramus and says the British are unique because they don’t care a damn about laws and contracts … I will be thinking of you as I drink the Bollinger.” Delmer died almost exactly 10 years later, not long after being attacked by geese at his Suffolk farm – but what a life he had lived. Brought up in Berlin before the First World War, where his Australian father was a professor of English, he was appalled by the barbarity of the Germans but believed they could still be democrats.

So in 1945, he drove through the bomb-flattened city of Hamburg on the orders of the Foreign Office, determined – in the words of his second biographical volume, Black Boomerang – to set up a new media which would “show the German press and radio how to free themselves from defects which in my opinion had helped to plunge a gullible German public into two world wars”. German press and media laws showed none of the respect for human rights and human liberty to which the British were accustomed under the rule of law, Delmer believed.

“German newspapers were free to destroy a man’s [sic] good name. The police, the public prosecutor, and other state authorities could denounce a man as being guilty of a crime before he had been brought before a court. Nor was there anything to prevent newspapers from anticipating the judgement of a court by volunteering their own opinions.” Having read some report of a crime in his newspaper Volkischer Beobachter, Hitler “would issue orders to the police to execute the man accused without waiting for a trial. And the police willingly obliged.”

The Germans, according to Delmer, were thus unable to distinguish between right and wrong, between what was fair evidence and what was not, “between morally good policy and immoral policy”. But if Germans could feel respect for the rights of their own citizens, they might also feel respect “for the rights of their neighbour states”. Although to Delmer’s great dissatisfaction, the post-war Adenauer government became stained with corruption and the employment of old Nazi cronies, Germany did indeed come to respect human rights – even, four years ago, those of a million refugees.

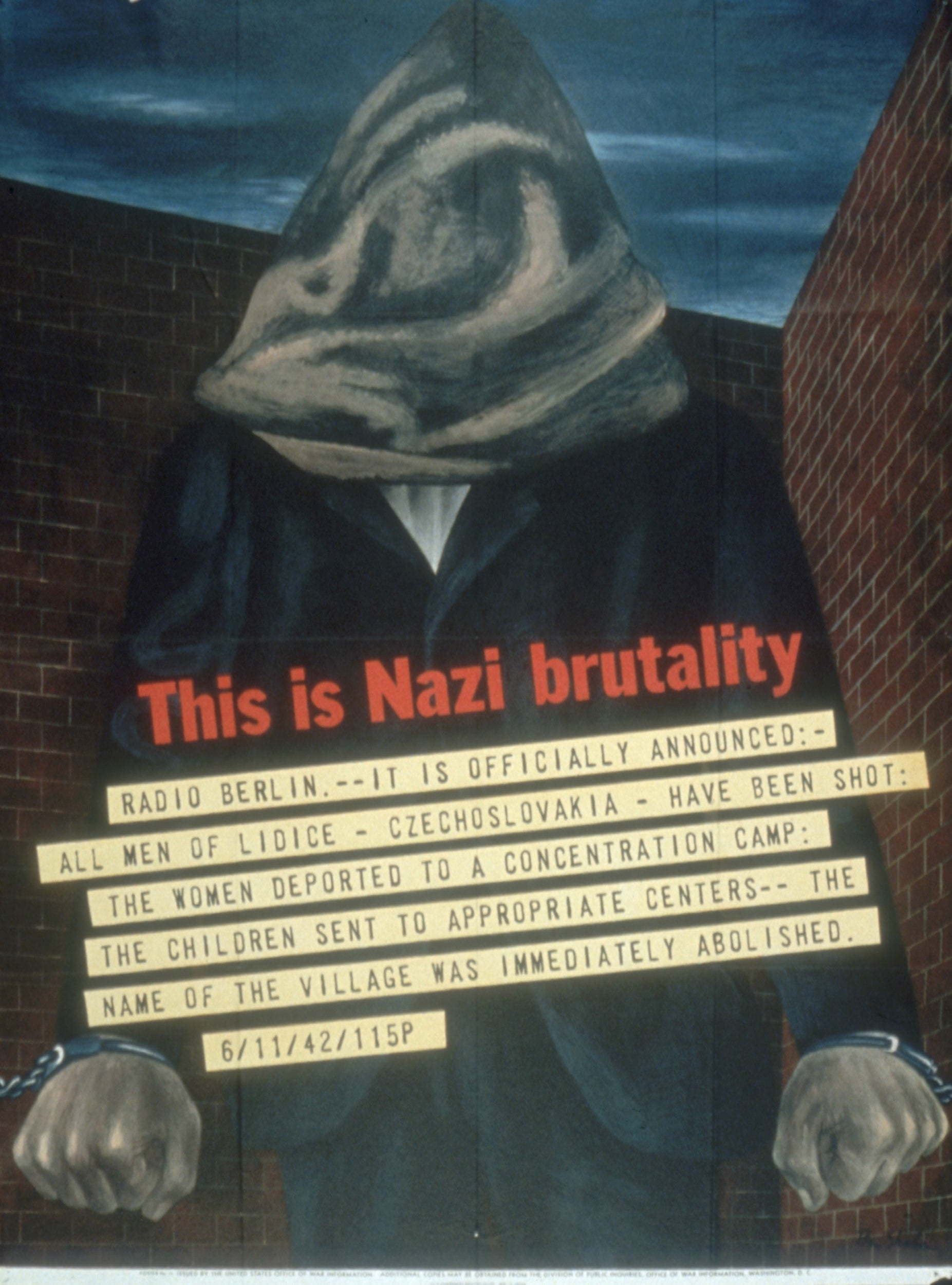

But Delmer would surely have understood the dangers of social media as surely as Hitler and Joseph Goebbels appreciated the ease with which radio could be used to poison the minds of listeners, to frame entire peoples as enemies of the state – the Jews, the Slavs, the French – without argument, opposition or legal restraint. The internet, which has become a “tool” of hatred, the antisemitic websites, the vicious tweets which can drive the innocent to suicide – all would have fascinated Hitler, who was obsessed with scientific discoveries. He was, in the words of his most recent biographer, “a gadget enthusiast”.

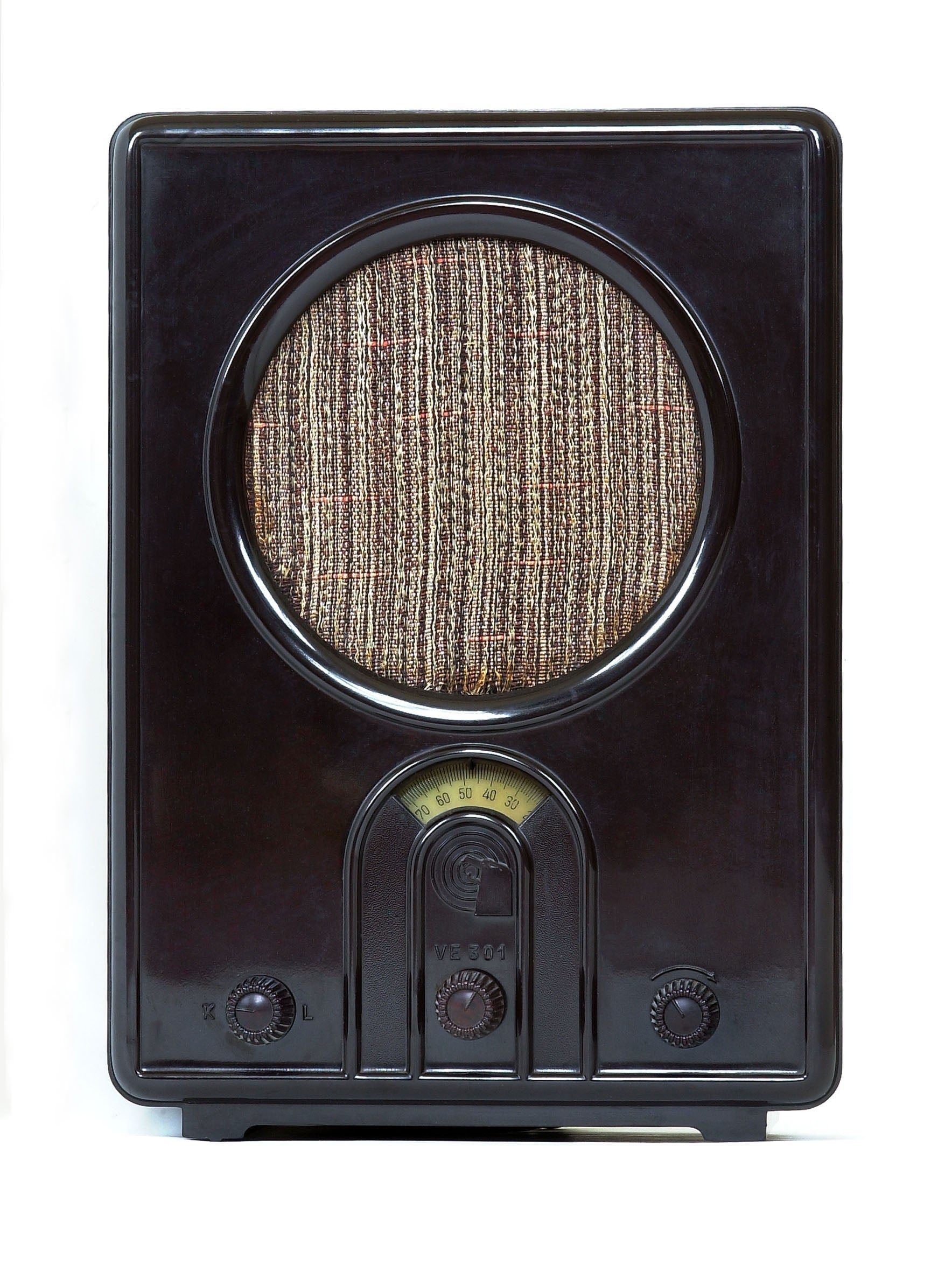

Volker Ullrich quotes Hitler as saying in 1942 that “I openly admit that I’m a fool for technology. Anyone who comes to me with some surprising technological innovation will have an advantage.” Goebbels kept the Fuehrer up to date on the progress of television, which he believed had a “great future” since people were on the threshold of “revolutionary innovations” – a local Nazi newspaper noted in 1938 that television would soon be as commonplace as radio. The model Volksempfanger VE 301 – the “people’s receiver” wireless – was unveiled at the Berlin Radio Trade Fair in August 1933, and 57 per cent of all German households owned a receiver by the start of Hitler’s war in 1939.

I was standing behind [O’Duffy] on a balcony when he addressed a rally of several thousand young Blueshirts. He was speaking very rapidly. It dawned on me that they were hanging on his words in a kind of obsessed way and I suddenly realised that he was speaking without any verbs. It had no discernible meaning. It dawned on me that if this fella told them to go and burn the town, they’d do it

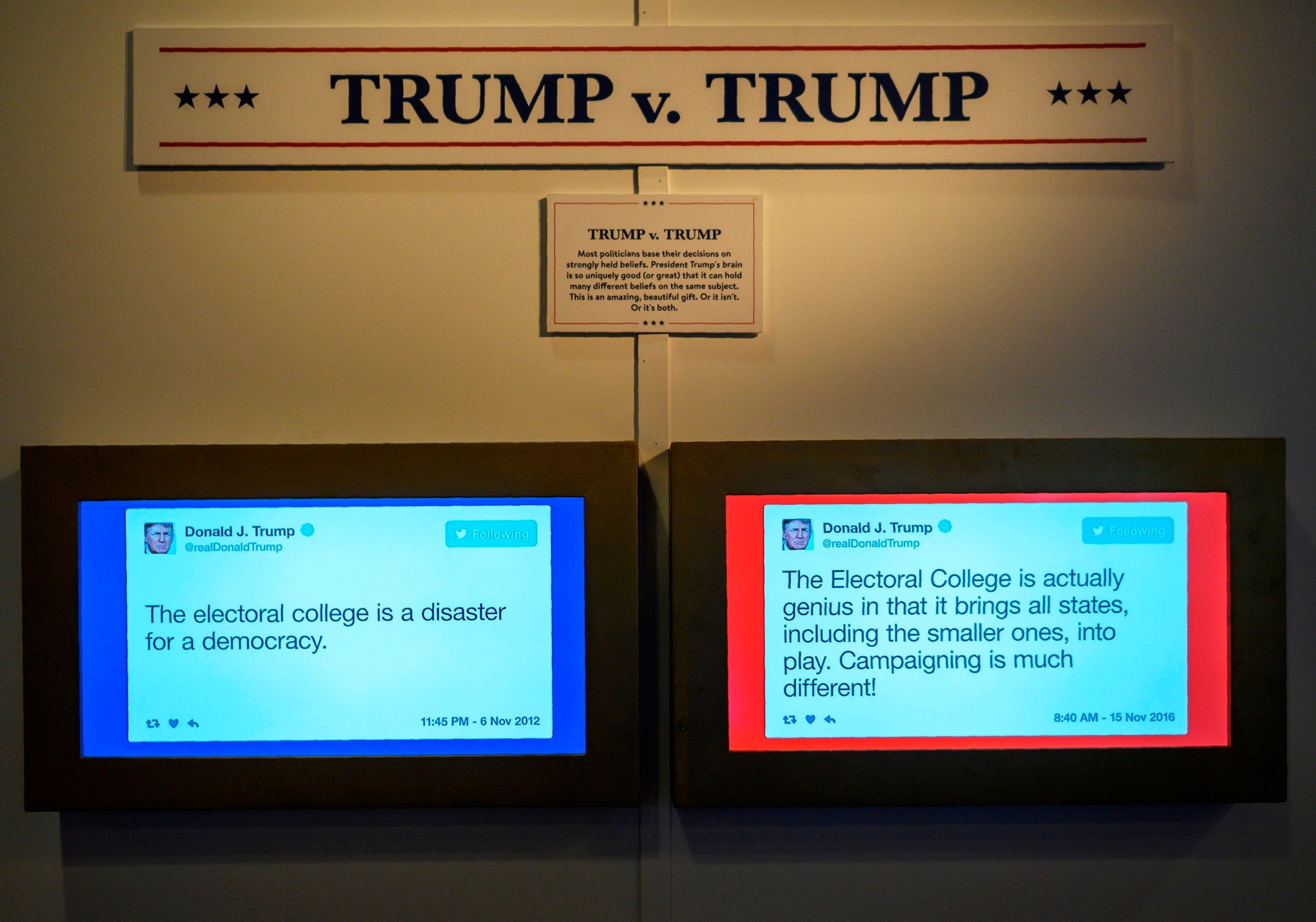

What primarily connects the world of Nazi propaganda and the tweet, however, is grammar – and anonymity (of which more later). What, for example, do the following have in common? “Blood and honour”, “One people, one country, one leader!” (Ein volk ein Reich ein Fuehrer!), “Strength through joy”. And “Big media con job”, “FAKE NEWS!”, “Corrupt media”, “Jobs, Jobs, Jobs!”, “No Collusion. No Obstruction”. The answer is obvious, although I still remember when the de-semanticisation of language was first brought home to me – by a former member of the Irish parliament whose lonely voice argued, during the Second World War, that Ireland should abandon its neutrality and fight for the Allies.

James Dillon’s appeals were ignored – quite rightly from an Irish political point of view – but he certainly had a claim to understand Nazism. Back in the 1930s, Ireland had a para-fascist Blueshirt movement – just as Britain had Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts and the Nazis had their Brownshirts – and Dillon’s membership of an Irish farmer’s party allied him with the Blueshirts, led by a former police commissioner called Eoin O’Duffy. Historian and former provost of Trinity College Dublin FSL Lyons was to remark that “whether for reasons of euphony or of irony, the chant of ‘Hail O’Duffy’ seemed somehow to lack the hypnotic effect of ‘Heil Hitler’”.

No matter. Dillon, a conservative Catholic of great personal integrity, spotted something deeply troubling about O’Duffy’s speeches in the 1930s, as he told me when he invited me to lunch in Dublin in 1979. “One day in west Cork,” he said, “I was standing behind [O’Duffy] on a balcony when he addressed a rally of several thousand young Blueshirts. He was speaking very rapidly. It dawned on me that they were hanging on his words in a kind of obsessed way and I suddenly realised that he was speaking without any verbs. It had no discernible meaning. It dawned on me that if this fella told them to go and burn the town, they’d do it.”

That is the key. Hitler also left out verbs. Tweets often leave out verbs. Dictators leave out verbs. Arab autocrats leave out verbs. Edward Said would rage to me about Yasser Arafat’s meaningless speeches in the late 1970s which would sometimes use phrases – “the victorious Palestinian people”, “the Israeli military junta” – without any sentence construction; without verbs. Was there not a Nazi slogan which read: “Beyond the enemy powers: the Jews”? Again, no verb.

This has now become a feature of much hate comment on the internet. Be it antisemitic abuse (which must include Arabs as well as Jews as a target) or Islamophobia or gender hatred, slogans are displacing argument. Thus, baldly and unsubtly, accusation has replaced debate. Every politician, journalist, activist, every prime minister, editor and clergyman (of whichever variety) now has to disprove the accusations made against them – however outlandish — in order to prove their innocence. They are guilty until proven innocent, the latter a happy outcome but one almost impossible to achieve since their guilt is already an internet “fact”, only put in doubt by responding to the contrary – and thus becoming part of the hate discussion.

In one sense, this creates not just a diminution of argument and free debate, but a step back to the inherent failures – or defects – which Delmer identified in German society in 1945, which “showed none of the respect for human rights and human liberty” to which we (in his case the British) were accustomed. And as he wrote, if you don’t show respect for your fellow citizens – whatever their colour, religion or origin – you won’t show respect for your neighbouring states. In Brexit Britain, that means Europe. In America, that means Latin American refugees, Iran and most of the Middle East – which can be offered either bombs (for Iran) or impoverishment (for the Palestinians) prior to an Arab-paid “deal of the century” (again for the Palestinian, but at the sacrifice of their rights to statehood). For Vladimir Putin, it means anyone, including millions of Muslims, who opposes Russian power. The same might be said of China. And, for refugees, Hungary. And now Italy.

There is no point in blaming technology for our plight. The same factory that makes bombsights for an F-35 can also make precision lenses for our spectacles. It is the use to which we allow that technology to be put – and the controls we choose to exercise over that use – which now confront us over social media. Facebook and Twitter and Instagram bullying – let us no longer defame the poor, Swedish folkloric cave creatures by using the word “troll” – has become a symptom of serious mental illness. Journalists – and we should speak up for ourselves – do not deserve, nor should we tolerate, the filth and slander which is thrown at us for doing our job by those people who, far from being worthy of attention, need serious medical help. Just as Hitler’s radio stations and newspapers denounced the innocent, so the innocent have today become victims of the internet.

This is partly because – like Hitler – each of us is a fool for technology. Trump too, of course. We long ago bowed to this supposedly progressive technological aspect of our lives. Technology was growing so fast and so wondrously that we were treating it as a god. It could not be questioned, could not be criticised; nothing could be said against it. Any suggestion that its contents might have to be controlled was scorned as an attack on free speech. This would be censorship. Hence those who swiftly understood the vicious, provocative, immoral uses to which the internet could be put – whether tweeting or social media or email abuse – were treated lightheartedly. Hence fascists were transmuted into those mysterious and mythical Swedish trolls. Thus the writer of what we would once have called a poison pen letter was softened and humoured. The bully wasn’t abusing or throwing dirt at us – merely trolling.

Although these men and women quickly realised how to control website comments and prevent all others from using them – because anyone who wished to avoid victimhood on the net would keep their own comments to themselves – we accepted their takeover and their character assassination in much the same way as the German people accepted the arrival of the Volksempfanger in their homes. The only thing we identified as wrong or flawed with this technology was technical – the battery didn’t last long enough in our laptops, or the screen faded in sunlight. For years, we did not reflect upon that aspect of our daily lives that would be attacked through this technology.

School bullying, for example, used to end when children went home at night. But cyberbullying continues after dark, through the school holidays – and then into the adult world. We are now all its victims – and it respects none of us. Unless we are silent. Unless we avoid all debate. Unless we allow the Volksempfanger to dominate our lives and tell us who is guilty – and then leave the guilty to the mercies of those who will execute them, socially or physically.

Hitler is dead, Trump is not Hitler and the crackpot in the White House is not the maniac in the Reich Chancellery. But Trump’s tweets enable the darker and more dangerous forces within our society to attack us

Delmer was, I think, a man with a conscience. On the telephone, we sometimes spoke about this. In the Second World War, he ran a number of “black” radio stations, ingeniously pretending to his German audience that they were actually run not by Allied – and often pro-Allied German – agents, but by rebellious Wehrmacht soldiers or Nazi officials who ostensibly worshipped Hitler but cursed the corrupt officials who surrounded the Fuehrer. The Soldatensender Calais, for example, was supposed to be run secretly by rebel German officers on the Channel coast, arguing that they had been forgotten and their comforts ignored in favour of soldiers fighting on the eastern front. An astute reading of real German newspapers by Delmer and his colleagues would furnish the names of Nazi officers to add veracity to the morale-breaking broadcasts of the Soldatensender. Captured Nazi documents would later prove how seriously the Gestapo took them.

But there was a brutal side to all this. On several occasions – to sow confusion in German cities – Delmer’s black station, pretending to be Radio Cologne or Radio Frankfurt or some other local Nazi transmitter, urged German men, women and children to leave the shelter of their homes for refugee camps shortly before an Allied air raid, so that they would be caught in the streets when the bombs began to fall. They would jam the roads and prevent German civil defence from putting out the fires – just as the Germans clogged the roads of northern France in 1940 by firing at French refugees and hindering the retreat of British troops to Dunkirk.

Driving into Germany at the end of the war, Delmer saw columns of refugees drifting down the autobahns in their tens of thousands, but he did not speak to them. “All were loaded with bedding and babies,” he wrote. “I did not stop to question any of them whether it was a message on Radio Cologne or Radio Frankfurt that had first started them on their trek. I did not want to know. I feared the answer might be ‘yes’.”

For Delmer and his Allied colleagues had been producing “alternative facts” to defeat the Nazis, fake news of the bloodiest kind, the ultimate murderous blog. He was therefore the right man to reform the German media, to insist that respect for human rights and liberty must come before the technology of the message, that the rule of law should prevail, that no broadcaster or writer – or troll, if we must use that wretched word – should be able to destroy a citizen’s “good name”. There must be no more denunciation.

Which is a good word for the contents of the Trump tweets, whether they be directed at his domestic antagonists, foreign enemies or British ambassadors. But at least we know who wrote these messages. Like a chocolate shop with an exclusive souffle, they are a speciality of the Trump presidency, a cannot-do-without part of the White House menu, a long-standing serial which rarely disappoints. And at least we can shoot back; we can denounce the denouncer, we can hold the lies to account.

It is the anonymity of the technology that blights our lives which is its most dangerous characteristic. With rare exceptions – including Goebbels himself, of course – German media articles and broadcasts after 1933 were written and produced by anonymous party members. Their words were all pervasive and insidious and racist. Germans knew who ran their radio stations. It was, after all, the Nazis who made the Volksempfanger – and its smaller version, the Deutscher Kleinempfanger – cheap enough for 11 million Germans to buy. But the voices of authority, the people who held the responsibility for the dissemination of hatred, remained largely anonymous. This is why war crimes trial lawyers spent so much time trying to identify Nazi criminals at the end of the war.

No, once more we must make the same old caveat: Hitler is dead, Trump is not Hitler – not even the former “little rocket man” (nor the supreme leader of Iran) represents the Nazi empire – and the crackpot in the White House is not the maniac in the Reich Chancellery. But Trump’s tweets enable the darker and more dangerous forces within our society to attack us. Semantics and the lack of personal responsibility is dangerously relevant.

So obvious in Europe three-quarters of a century ago, this anonymity, I suspect (yes, along with the absence of verbs), is what really gives power to the internet hatred of our own day. It applies to political abuse, personal threats, child pornography. As I often tell colleagues in the Middle East who reel back from the enormity of the malice directed at them, if we journalists have bylines on our stories – if our identity is (and should) be published with our reports – then the same must go for those who slander and smear us. Or for those who break the laws and contracts of which Delmer spoke in his 40-year-old letter to me.

Even that great British institution Who’s Who used to carry Hitler’s address: 77 Wilhelmstrasse, Berlin. So why shouldn’t the little Hitlers of today tell us who they are?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments