‘These are all fake news,’ said the honour student – he was wrong

In a class on news literacy, instructors contend with a new era of unbridled skepticism

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This autumn, 16-year-old Chris will be taking IB (International Baccalaureate) in Maths, IB Business, IB Literature and IB Physics at Annandale High School in Northern Virginia. “IB” means the classes are part of the rigorous International Baccalaureate programme, which means Chris is, as he put it, “super smart.” So committed to being smart is Chris that he chose to spend one of his final days of summer at an IB prep programme he heard would look good on his university applications. And that’s how Chris ended up in the classroom where he – and all his super-smart classmates – were about to discover a subject that they were not so very smart about.

“What,” asked their instructor for the day, “is fake news?”

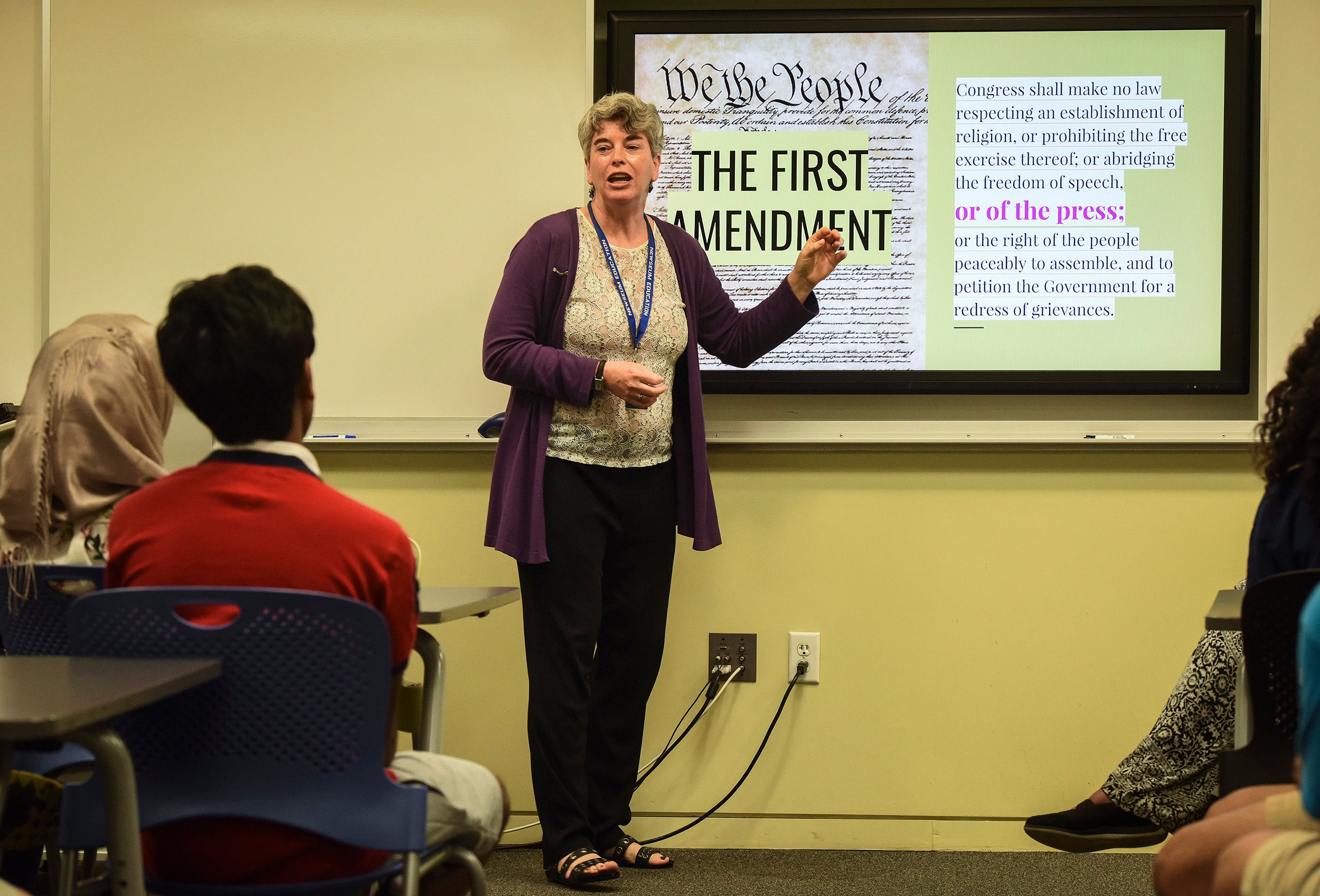

Hands shot up. Kim Ash, an educator at the Newseum, assessed the room full of rising juniors and seniors. Of course they’d heard of fake news. President Donald Trump has tweeted the phrase more than 100 times since taking office. It punctuates jokes, appears on T-shirts and always seems to be the subject that even international visitors to the journalism and First Amendment museum want to ask her about. These days, people shout “Fake news!” just because it’s fun to say.

The young people sitting before Ash had spent some of their most formative years hearing that the news is fake. For the teachers responsible for educating them, this is a new problem.

While they once feared teenagers would fall for everything they read online, now teachers are increasingly concerned that their students will grow up not believing anything they read – or worse, believing the difference between what’s real and what’s fake is a matter of choice.

Early this year, the Newseum developed a class called “Fighting Fake News”. By the time it launched in May – typically one of the slowest months for school trips – it was almost immediately booked solid through June. In those sessions in the museum’s basement classroom, it didn’t matter if the students came in wearing “Make America Great Again” hats or Ruth Bader Ginsburg T-shirts, they struggled to differentiate fact from fiction.

Still, Ash remained optimistic about the future of America’s relationship with the truth. “Sunshine on the issue is the best disinfectant,” she had been telling fretful colleagues. She picked up a heap of printed articles and passed them out to the Annandale students. Their task: Figure out which ones are real.

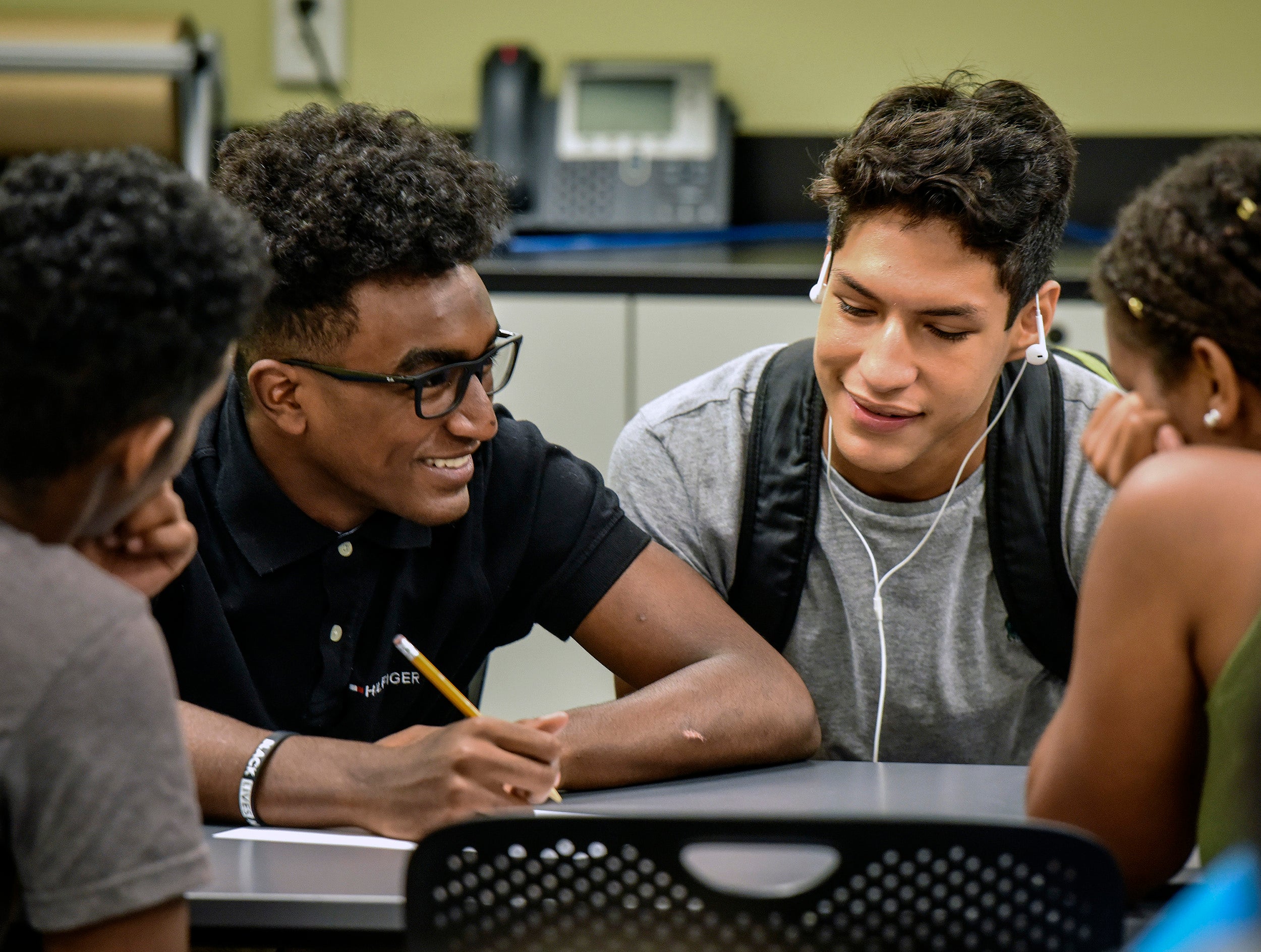

In a group near the back of the class, Chris flipped through each story, reading the headlines, squinting at the photos, analysing the first paragraphs.

“These,” he announced to his friends, “are all fake news.”

They were not all fake news. Within the pile were true stories of Pepto Bismol-coloured water pouring from faucets, a tornado spiralling alongside a rainbow and the President of the Philippines urging citizens to kill drug dealers.

Instead of distributing articles and photos from big-name news sources, Ash selected content from lesser-known, online-only sites, the type likely to appear on social media for Chris and his classmates.

Across from Chris, a 16-year-old named Ruth sifted through the pile. She didn’t necessarily want to agree with him, but she had long shared his suspicions about bogus stories. Too many people are out there trying to get you to click on something, she said. And usually, she does click. She just doesn’t assume what that what she reads is true.

Now she picked up the story about pink water. To Ruth, it seemed unlikely. Even though there was a photo, it could have been Photoshopped. So she set it in the “fake” pile.

That’s where the group stacked all the stories they read, in fact, until one of the headlines caught Ruth’s attention: “Harambe, A Dead Gorilla, Got Over 15,000 Votes For President Of The United States.” Beside the headline was a photo of the internet-famous primate, who became fodder for memes after his death at a Cincinnati zoo last year.

“Didn’t this actually happen?” Ruth asked the group. She thought she had heard something at school about Harambe and the election.

Her friend Ayman searched online for the source listed below the headline, a website called the Daily Snark.

“It’s verified on Twitter,” he said. “This one could be real.”

Chris went to DailySnark.com, and found a page filled with other seemingly realistic stories. He clicked on one about the Jacksonville Jaguars replacing its quarterback, which seemed like a pretty normal thing to write about in a news story. Soon, they were all convinced – except their friend Idris.

“There’s no way,” Idris told his friends.

Idris’ parents had always watched the news: the Today show in the morning, NBC or CNN at night. He never paid much attention to it until high school, when he took a government class, which he said made the news seem pretty interesting. Now, he checks what’s going on in the world 10 or 20 times a day – on Twitter. That’s where he learned not to believe just any account, simply because it had a word like “news” or “daily” in its username.

“How would a gorilla get votes if it wasn’t on the ballot?” he asked the table.

“Have you ever seen a presidential ballot?” Ayman said.

“You can’t even vote,” Idris snapped back.

“Yeah, but I’ve seen it,” said Chris, and he launched into an explanation of write-in votes. “Trust me,” he said.

Idris looked at Ruth.

“I’m not even playing,” she said. “It’s real.”

“I guess I’m just an idiot,” Idris said, and from the front of the room, Ash announced that time was up.

“Pen or pencil down,” she said. She went through each article. Fake, real, fake, fake. She showed the students the subtle red flags that might have tipped them off to the fakes, such as quotes from an “expert” whose name can’t be found elsewhere online.

But quickly, she found herself having to convince them that some of the stories weren’t fake at all. The pink-water story, for example – if they had looked, they would have found it on multiple well-known reliable news sites.

“Your gut can only take you so far,” Ash said. “Don’t be intimidated. If you see story and you’re asking, ‘Is this true or not?’ You have the power to find out.”

Chris raised his hand.

“Can we go over the Harambe one?” he asked.

Ash paused.

“It’s fake,” she said.

Chris smacked the table.

“I told all of you!” Idris said.

Ash pulled up DailySnark.com on her screen and scrolled to the “About” section, where it explained the site is “sports, news and entertainment satire.”

Defeated, the students at Chris’ table moved Harambe to their fake news pile. It was the only story they’d been given that they had thought was real.

After class came burgers, fries and pizza in the Newseum cafeteria, which made Chris think of Papa John’s, where he works. He started to tell his friends about what happened the other day on his break.

He was about to take a bite of pizza topped with barbecue chicken and bacon, he recalled, when a co-worker shouted, “Don’t eat that!” She went on to tell him about a new food documentary on Netflix called What the Health. He went home and watched it.

He learned that meat causes cancer. That fish causes cancer.

“One egg,” he told his classmates, “is as bad for you as five cigarettes.”

Ruth, Ayman and Idris were appalled. Later, if they were to look up the documentary in question, they would find that it has been widely criticised by scientists, and many of its inflammatory assertions have been debunked. But for now, the students had a new set of skills with which to deploy their skepticism. The questions came at Chris from all sides of the lunch table.

“Did you fact-check this?”

“What’s their source?”

“Did you search up the people in it?”

“Where’s the proof?”

Chris’s didn’t seem to mind.

“It’s all real,” he said, and took another bite of his burger.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments