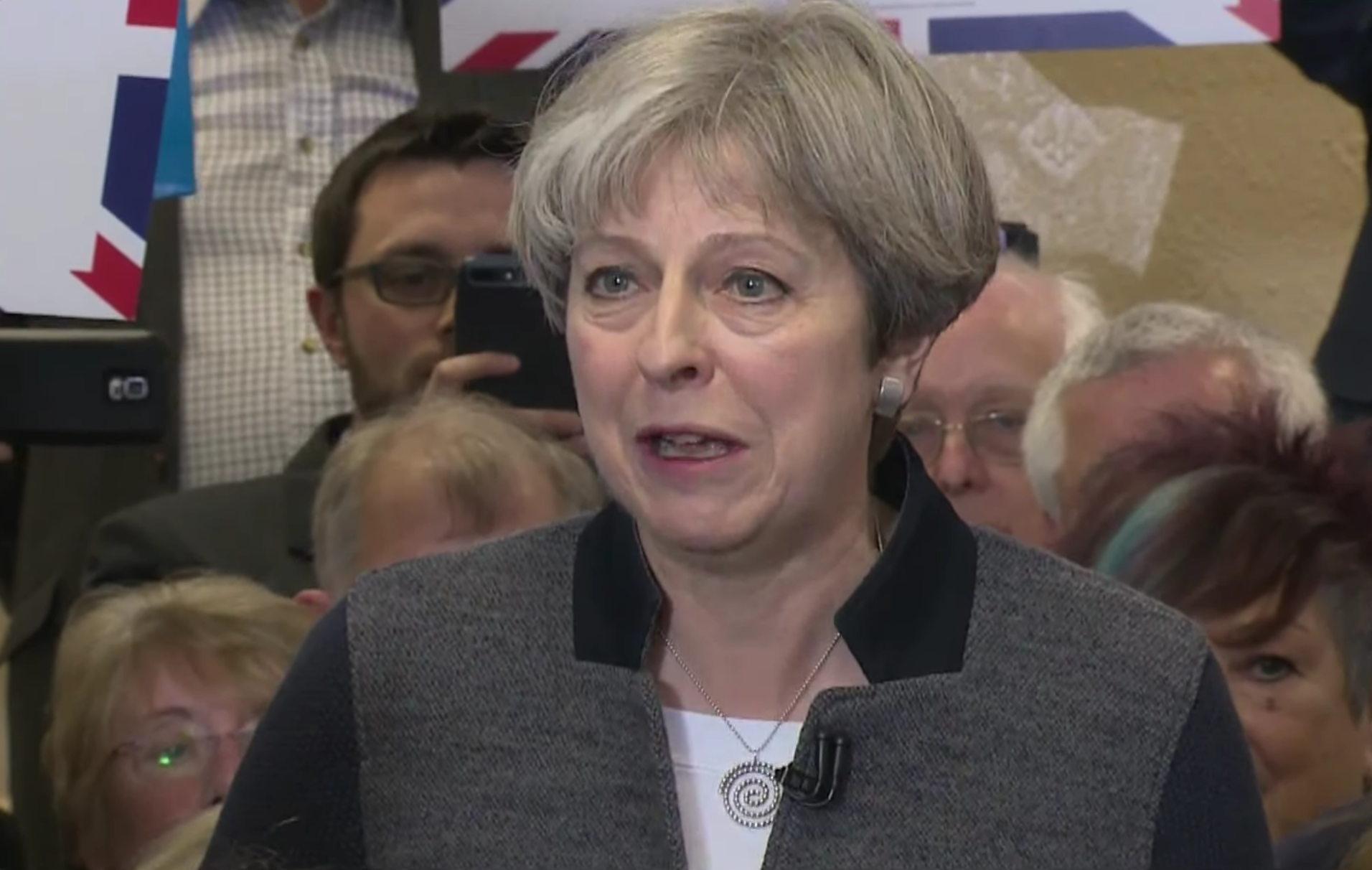

Two years after coming to power, Theresa May's premiership is the most shambolic for a century

May’s principal achievement in her short time in office is simply survival but even this cannot be counted a positive accomplishment of her own making

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You doubt that it bothers her much, but there will never be such a thing as “Mayism”: a strong body of ideas and convictions that can drive a political party and a government forward – give it momentum, if you will.

When Theresa May was left as the only grown-up in the room after the Tories’ more-than-usually nasty leadership contest two years ago, there was some loose talk about Theresa May being “the new Margaret Thatcher”, the last British leader to lend their name to an “ism”.

Perhaps, some supposed, we’d also one day talk of Mayism: of a kinder, gentler, humbler Toryism. It didn’t quite work out that way. In due course we’re more likely to get Maoism under Jeremy Corbyn.

Still, when May was asked by the Queen to form a new government, the statuesque new premier curtseying like a giraffe at the waterhole as she lowered her tall frame to meet our diminutive monarch’s hand, there were some high hopes, and much goodwill.

In her first statement in Downing Street, May pointed the way. Like her predecessor, David Cameron, she planted her party in the centre ground, but signalled too that she wanted to have fewer public schoolboys around the cabinet table, and to pay a bit more attention to those “left behind”.

She hinted that she had learnt a political lesson – and wished to appeal to the people who had helped deliver the Brexit vote that killed David Cameron’s career, and forever destroyed his reputation. (Whatever else, May can always console herself that history will treat her more kindly than her immediate predecessor, and she will only ever be the second worst premier since the Second World War).

In what seems a political age ago, she declared that “David Cameron has led a one-nation government, and it is in that spirit that I also plan to lead”. It’s probably worth quoting at length what she felt that meant, to judge it by the situation today:

“That means fighting against the burning injustice that, if you’re born poor, you will die on average nine years earlier than others.

“If you’re black, you’re treated more harshly by the criminal justice system than if you’re white. If you’re a white, working-class boy, you’re less likely than anybody else in Britain to go to university. If you’re at a state school, you’re less likely to reach the top professions than if you’re educated privately.

“If you’re a woman, you will earn less than a man. If you suffer from mental health problems, there’s not enough help to hand. If you’re young, you’ll find it harder than ever before to own your own home.

“But the mission to make Britain a country that works for everyone means more than fighting these injustices. If you’re from an ordinary working class family, life is much harder than many people in Westminster realise. You have a job but you don’t always have job security. You have your own home, but you worry about paying a mortgage. You can just about manage but you worry about the cost of living and getting your kids into a good school.

“If you’re one of those families, if you’re just managing, I want to address you directly.

“I know you’re working around the clock, I know you’re doing your best, and I know that sometimes life can be a struggle. The government I lead will be driven not by the interests of the privileged few, but by yours.”

Today, after Grenfell, after the Windrush scandal, after revelations about the “hostile environment” for migrants, after more austerity, after the blunder of universal credit, after a further squeeze on living standards, there is precious little sign of much tangible progress.

The Jams (“just about managing”) are still Jams, though the acronym’s been dropped.

Britain is, if anything, even more divided and less “one nation” than it was that summer. Of the all-consuming project that might have defined May’s premiership in a good way – Brexit – she then said little. That was because, on day one, she didn’t quite know what to do with it, which perhaps was understandable. More disappointingly, on about day 730, she still doesn’t. Brexit has come to overwhelm her and define her premiership – and has done so in a historic, catastrophic way.

Some of it was hardly her fault. May inherited the mess that Cameron’s referendum left behind, and has been trying to have her cake and eat it ever since, a constant battle against EU theology and logic that has seen her cabinet rotate in ever decreasing circles.

The best minds in Whitehall, Westminster, and some in Brussels for that matter, have been set on the task of finding yet more novel ways to simultaneously enjoy all the benefits and none of the costs and obligations of the EU customs union and single market respectively. Yet the riddle of the Brexit cake remains unsolved. We don’t have Mayism, but we do now have “cakeism”.

The effort to leave the EU and to have no border “infrastructure” on the island of Ireland is just the most lethally dangerous subset of the same over-arching logical puzzle. If only for that reason it usefully concentrates minds.

Thus, the entire history of British politics and the May premiership since it began in July 2016 can pretty much be summed up as a two year Star Trek-style mission led by Captain May and her mixed ability crew to boldly go and explore new ways of having the European cake and eating it – while ultimately achieving virtually nothing.

Might things have been different?

May, like all premiers, can do little about what Harold Macmillan famously called “events, dear boy”. She couldn’t do anything about the Brexit vote, whatever she might have privately wished it to be, and, to be fair, she gamely took up the challenge of obeying the will of the British people to deliver a “red, white and blue Brexit.” In the early days it all sounded quite jolly, did Brexit.

During the leadership contest she had displayed simple competence. By contrast, Boris Johnson, Andrea Leadsom, Michael Gove, Liam Fox and Stephen Crabb (if you remember him – beard, Welsh, personal issues) had proved that they couldn’t even run a leadership campaign. There’s no evidence that any of the other contenders would have squared the impossible circles any more successfully than May.

Nor could May be held responsible for inventing Boris Johnson, a man who believes he possesses all of Winston Churchill’s virtues, but none of his flaws. (The reverse being, of course, the case with Bozza). He would destabilise anything he touched.

What’s more, May had no choice but to end up with a mostly intellectually underpowered cabinet, delicately balancing Remainers and Leavers. There was, to borrow a phrase from an earlier age, no alternative but to have Fox and David Davis in two of the most crucial positions in government.

Later on she had no role to play in the personal embarrassments of Damian Green or Sir Michael Fallon, though she could be faulted for using Amber Rudd, home secretary at the time, as a human shield after the Windrush scandal broke.

But May did have a choice about the snap election she called last year – the great unforced strategic error of her life. Strangely for such a usually cautious politician, she gambled and lost. Lost, that is, more than just her majority, grievous though that was. She lost a reputation for judgment – which is what leaders are supposed to be for. As a result she lost her authority, which, before the election had been absolute, difficult though that may be to credit now.

Don’t laugh, but for a brief moment Theresa May really did bestride British politics like a colossus, like Thatcher or Blair in their pomp. Her Tory rivals were vanquished, if not humiliated, the Lib Dems and Ukip virtually irrelevant, the Labour Party in mortal fear of destruction, the media universally ready to write-off Corbyn as Labour’s death rattle and speculate endlessly about the “challenges” Theresa May would have in managing a Commons majority of 100-plus.

It all sounded so easy. She apparently made the decision to call the election early on a walking holiday in Wales with her husband Philip (like the shopping expeditions to the local Waitrose, and shared passion for cricket, it offered quite a revealing little glimpse into their middle England tastes). It was meant to be the moment when her strength and her legacy was secured; it became instead the turning point in her premiership.

It is true that the advice she received about the early poll, the Conservative manifesto on which she stood and the tactics she used, all disastrously, were the product of a strategy developed by her closest advisers, Fiona Hill and Nick Timothy. Yet it was May who appointed Hill and Timothy, the terrible twins, at the Home Office and who subsequently made them co-chiefs of staff at No 10.

Moreover, she did not have to do everything they told her to. She chose to however, disregarding along the way cabinet colleagues who could see the downsides. She carries the can.

As it a happens, her advisers’ ideas about the future of long-term care – the so-called “dementia tax” – had rather more merit than they were ever allowed, being more favourable to poorer sections of society – but the press destroyed May’s policy anyway. A rapid U-turn was spun as an example of determined consistency of purpose. The public, in response, began to laugh at her, rather than fear or respect her; just as they had with Gordon Brown, in 2010. It was a fatal moment for her as it had been for him.

In truth, the whole election campaign was lacklustre, characterised as it was by repetitive soundbites. May became known as the Maybot. Her contribution to collections of prime ministerial quotations say everything about her politics, because they say everything about its hollowness: “Nothing has changed”; “Brexit Means Brexit”; “Strong and Stable”. As a nation we are by now conditioned with Pavlovian certainty to know that when May starts a sentence “let me be absolutely clear about this”, then she is going to be anything but.

When the election was lost and her advisors were forced out, May was left with little room for manoeuvre to appoint people in her own image. She was forced to retain Philip Hammond as chancellor, and Sajid Javid in cabinet, when she would have preferred to jettison them; and she was forced to bring Michael Gove back in, a man who she, Hill and Timothy had fought a guerrilla war with when she was home secretary and he ran education. Old scores were settled, and not in May’s favour.

She was, quite frankly, lucky to survive (or not, if you want to feel sorry for her).

The PM let it be known, or others did for her (possibly with less authority than they purported to possess), that she would not lead her party into another general election, and that she only wished to get herself, her party and her country out of the mess that she had gotten them into – an odd sort of pitch for power if you think about it.

Almost at a stroke May had turned from colossus to pygmy. She was a premier on sufferance, there at the whim of the backbench 1922 Committee, crimped and cramped by the parliamentary arithmetic, unable to take bold decisions about people and policy.

When the time came to reshuffle her cabinet, ministers such as Jeremy Hunt at health simply ignored her and turned up for work the next day anyway. Boris cheeks her on almost daily basis, with impunity. May is unable even to have her own advisers (though the current crop are a vast improvement on the terrible twins). At this most critical juncture she is unable to take the country forward, unable to fulfil her early promise, unable to shut up the absurd Jacob Rees-Mogg – and perhaps unable to deliver Brexit of any orderly variety. She doesn’t even seem to be able to rid the country of plastic coffee cups or making the trains work.

So far from sparking a renaissance, a buccaneering sense of adventure for “global Britain”, Brexit has engendered only trepidation and a sense of national malaise. May means drift, damage-limitation, buying time: and it will surely get worse.

True, governing Britain after the Brexit vote was never going to be easy. Doing so with the landslide majority she was supposed to win in the 2017 general election might well have made matters a little more straightforward, however. That was, after all, why she asked the country to let her form a more “strong and stable” government with a clear mandate for Brexit (and the Remainers duly extracted their revenge).

In the parallel world of May dominance, the intrinsic incompatibilities of Brexit would be the same, but the May government would have been able to opt for one side or the other, and would have commanded a majority in the commons to see it through. Probably. With the slim majority of 12 that Cameron left behind it was trickier. With what she ended up with, it is virtually impossible, the slightly desperate deal with the DUP making little difference. She has been fortunate that her internal foes, such as Dominic Grieve, appear to lack nerve.

So Theresa May has made the best of things, even when they haven’t been very good at all. The nadir, so far, arrived at the Tory Party conference last year, when she delivered the worst speech in modern times – coughing all the way through, as the backdrop collapsed behind her and a prankster publicly handed her a P45. As New Labour used to sing, “Things Can Only Get Better”. Except they won’t.

May’s principal achievement in her short time in office is simply survival. Even this cannot entirely be counted a positive accomplishment of her own making, because much of it is down to the simple fact that no one can easily agree on who should replace her. Many think it wouldn’t make much difference to the reality of Brexit now, and the bloodbath would be against the party, and the national, interest.

As such, she seems set to stick around until Brexit, whatever that means, is delivered. She remains, as George Osborne so memorably observed last year, a dead woman walking; but, equipped with Nordic skis, she staggers on her zombie-like progress towards nowhere in particular.

Be there no doubt, the May administration has been the most shambolic in the past century or more.

Indeed, she herself is an unusual type of leader because she lacks so many basic political skills. In many ways she resembles not Cameron or Thatcher, nor Hague and Duncan Smith (who she served as party chairman, when she invented the albatross phrase “nasty party”). No, she is much more reminiscent of Ted Heath, his Europeanism aside.

Born in 1956, Heath’s leadership coincided with May’s political awakening – she was 19 in 1975 when he was replaced by Thatcher. That transition of course, planted the notion that a female could get to the top in the mind of the ambitious Theresa Brasier. But May is no true Thatcherite. When she permits herself, she sometimes displays the same corporatist sympathies as Heath – even once wistfully talking about worker directors on the boards of big companies; and she is unusually insistent, for a post-Thatcher Tory, on strengthening workers’ rights and spending more on the NHS.

Like Heath, May is prone to U-turns, trusts no-one beyond a tiny circle, and favours a bunker mentality in No 10. Above all, again like Heath, she is shy and finds mixing with the public and her backbenchers distasteful. She can fall silent in conversation for an uncomfortable length. She is visibly ill at ease with the voters, in stark contrast to Corbyn, Blair, Farage or even Cameron. She is more akin to Gordon Brown, also the child of a clergyman, who shared her dedication to public service and sense of duty, but suffered also from mild paranoia and morbid terror of a walkabout or a TV studio.

Really, May comes across as being much more of an administrator, a civil servant manqué, than a classical politician. There is a reason why the first job she took after university was as a Bank of England graduate trainee – a civil servant in all but name and at a place where the “common touch” is no great advantage.

The prime minister’s curious shortcomings at being an actual politician – after all, she spent a good deal of time at the grubby end of the game in local government – let her down badly in the 2017 election, and again after the Grenfell disaster, and continue to do so on TV. (One recent appearance was said to be like a hostage video). She can be dignified and sensitive, as she has shown after terror attacks, but more often she seems to lack a certain instinct about the right thing to do for the “optics”.

Perhaps some of this is down to simple shyness, which is why the prime minister sometimes looks so lonesome at EU summits, and why she never really hit it off with Donald Trump (he thinks she talks to him the way a schoolmistress would address a dim pupil). She is said to get on best with the similarly unfussy Shinzo Abe, prime minister of Japan.

In any event, it is these tragic flaws in her make-up – the nervousness, brittleness, shyness – that explain why she lost her snap election, and why her premiership has subsequently been such a disaster. Even without Brexit she’d have been a flop; Brexit just adds to the scale of the failure – although, ironically, it has also artificially extended her tenure in Downing Street.

Theresa May’s abiding legacy will turn out to be blue British passports, printed in France. Let me be absolutely clear about that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments