The other ivory trade: Narwhal, walrus and... mammoth

They may not attract the same headlines as African elephants, but there are several different species traded on the international market today

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

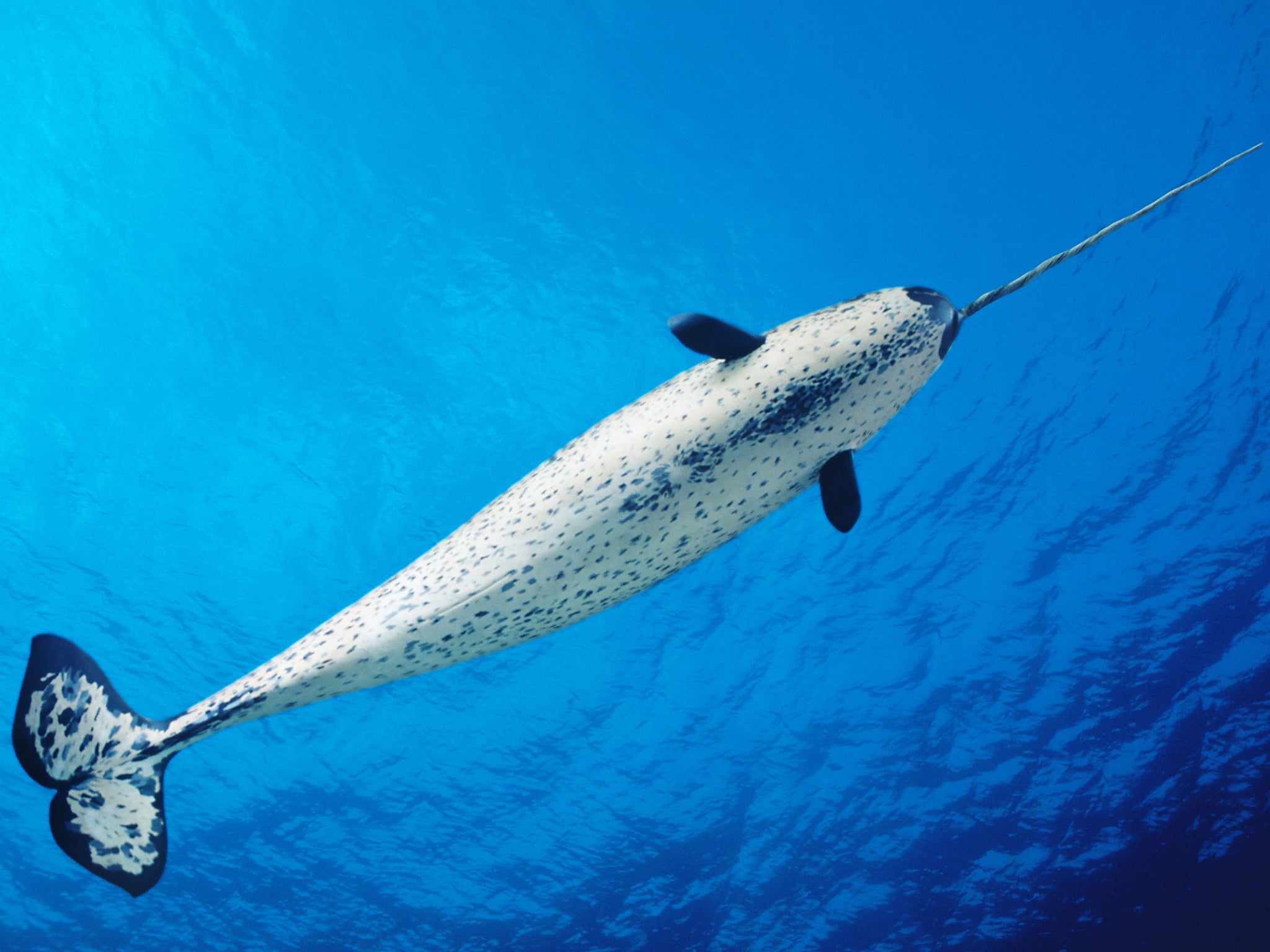

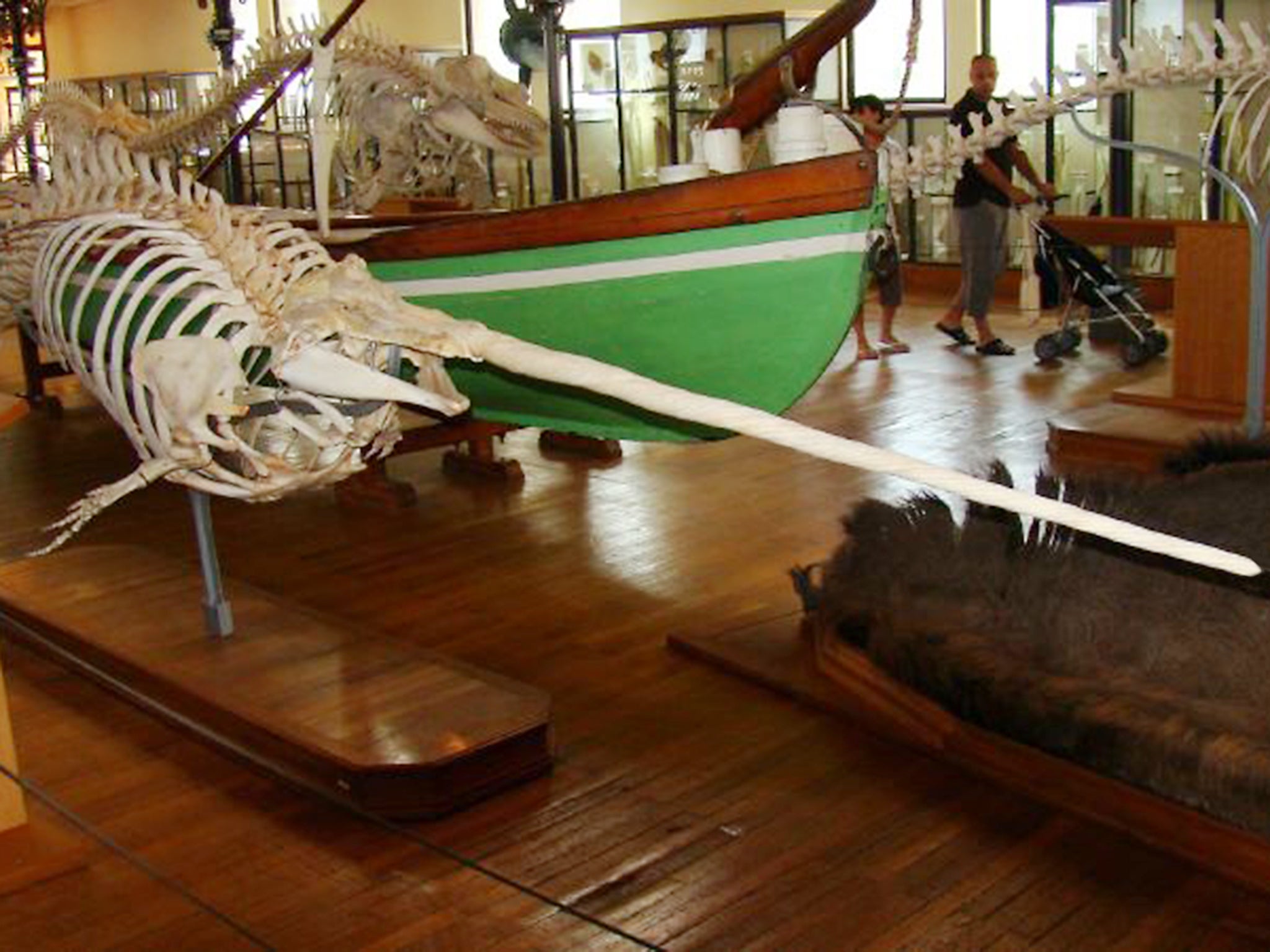

Your support makes all the difference.Considered to be a “sea unicorn” in the centuries before the Arctic was properly explored, the “horn” of the narwhal was an object of fascination for Europeans, and particularly monarchs, who paid for the tusks with many times their weight in gold.

Queen Elizabeth I is said to have spent £10,000 on a narwhal tusk, a fortune in Elizabethan England, roughly equivalent to £1.5m today, and had it placed within the crown jewels.

Although no longer considered to be the horn of the unicorn, today the average price of a narwhal tusk is around £3,000 to £12,000, while rare “double tusks” can fetch as much as £25,000.

A species of toothed whale, the narwhal can grow to be more than 5m long and live for up to 50 years. A relative of the white beluga whale, narwhal grow a helical unicorn-like tusk that is actually a protruding canine tooth. The exact use of this unique feature is still debated by scientists, with recent studies suggesting it is a highly sensitive organ used for detecting temperature and chemical differences in the water.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature does not consider these species to be at immediate risk, but the 75,000 narwhal alive today are now considered to be “near threatened”. In practice, this means narwhal could soon become vulnerable due to changes in their natural environment and the impact of hunting.

Canada and Greenland permit the hunting of narwhal by the native Inuit for subsistence purposes, landing an average of 979 whales a year between 2007 and 2011. The Inuit have hunted narwhal for centuries, using the animals as both a source of food and income.

In addition to the global trade in tusks and teeth, a Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society study found that shops in Japan were selling ground narwhal tusk as a tonic to treat fever, measles, venereal disease as well as general pain relief. Shop counter prices for this medicine varied from $540 (£421) and $929 (£724) for 100g.

A WWF and Traffic report from 2015 warned that the effects of climate change means the hunting of narwhal needs to be better monitored and regulated, but did not consider the international trade in narwhal parts to be a threat to the survival of the species today.

Noting the significant economic and cultural importance of the narwhal to Arctic peoples, the report said: “Successful management will result in populations and stocks that are healthy, stable, resilient to threats and a continued resource to local communities.”

The report called for: “More consistent reporting of CITES trade data. More precise reporting of the narwhal body parts in trade. Reporting of items exported as personal and household effects (souvenirs). Developing a study on the supply chain and consumer demand dynamics for narwhal parts.”

The Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society is concerned that the hunting of narwhal has already become unsustainable.

“Narwhals have been ‘overharvested’ in Canada and Greenland, raising cause for concern,” the organisation said.

“The annual hunting in western Greenland (since 2004) significantly exceeded the quotas recommended by those scientific bodies of regional and international organisations charged with narwhal management.”

Aside from hunting, the WWF cites a number of growing threats to the sustainability of the narwhal population, including underwater man-made noise generated by the oil and gas industry as well as military activity. As whales use sound for navigation and communication, this can be very disruptive to species such as the narwhal.

Unsurprisingly, climate change is high on the list of threats to narwhal. These whales use the ice to hide from predators, and lower sea ice coverage in the Arctic makes the whales more vulnerable both to hunting by man and natural predators such as killer whales.

Although the Inuit people are permitted to sell narwhal derivatives, in both the United States and the European Union, there are complicated sets of restrictions on what can and cannot be imported without permits and penalties for contravening import rules can be expensive.

A joint US-Canada anti-smuggling investigation known as Operation Longtooth uncovered a significant and profitable illegal trade in narwhal tusks in the United States. In 2013, Gregory Logan was arrested in the US for offences relating to a staggering 250 narwhal tusks, resulting in a fine of $385,000 and an eight-month conditional sentence. In 2015, United States v Andrew Zarauskas saw the defendant sentenced to 33 months in prison for “unlawful trafficking of narwhal tusks and teeth”. The animals in question were hunted legally, and lawfully purchased in Canada, but the re-selling of these items is strictly prohibited in the US.

In 2009, seven narwhal tusks were legally put up for sale with prices ranging from £500 to £10,000 each in a “Gentleman’s Library” auction at Bonhams, before being removed following a campaign by the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society, which argued that the high prices would further encourage the global trade in narwhal parts.

Like the narwhal, the carving of walrus tusk goes back many centuries. Yupik, Inuit, Inupiaq peoples are believed to have made ornamental walrus tusks as far back as prehistoric times, while Northern Europe’s interest in walrus emerged later.

The Vikings are thought to have started trading walrus ivory when the Conquests restricted the supply of elephant tusks from Africa, with England’s King Alfred the Great amongst the recipients.

Also like the narwhal, the walrus is subject to complicated hunting and export rules, and there have been reports that the international regulations aimed at preventing the sale of elephant ivory is inadvertently hurting the Alaskan communities who carve walrus ivory for a living.

Exempt from the US Marine Mammal Protection Act, Alaskan Natives are one of a number of Arctic communities that are permitted to hunt the walrus for both meat and sales of “worked” ivory, within restrictions by countries with territories in the Arctic. The WWF estimates an average of 5,406 walrus were hunted from 2006-07 to 2010-11, which “equates to less than 3 per cent and 4 per cent respectively of the estimated global populations for each subspecies”.

As remains the case for a lot of the scientific research taking place in the Arctic and Antarctic, poor data has prevented conservationists and scientists from accurately assessing the current condition of the Arctic walrus populations. Another WWF and Traffic report concluded: “Limitations in available trade data make it very difficult to make inferences on the impact of international trade, whether current provisions and regulations are adequate and whether further action is needed.”

Walrus are not considered to be an endangered species but the tightening up of restrictions on the sale of ivory in states such as California, Hawaii, New York and New Jersey, as well as negative press concerning the sale of elephant ivory around the world, is thought to be having an impact on the traditional craftsmanship of communities in the region.

Yet with many marine mammals protected from human exploitation, and most whaling banned by the International Whaling Commission since 1982, the Arctic permits stand out as an anomaly.

“There are some Alaskan communities who really rely on the income they receive from walrus ivory to sustain their lives,” says Tanya Shadbolt, a freelance environmental consultant who worked on the WWF/TRAFFIC reports. “It’s very easy for scientists to come in and say ‘you can’t do this’, without understanding the impact on people, and vice-versa.”

“Some Inuit can get upset and they can end up disliking because they see people coming in and making decisions that affect their livelihoods and they don’t have a voice in it.”

“Science informs management decisions, it is needed because the information collected is what is used to monitor the species and ensure the population is doing ok. For me, what stuck out the most from this research was the delicate nature of the situation. Everybody wants what is best for the species. The Inuit want what is best for the species too, they rely on them.”

The global trade in ivory is not restricted to species that are alive today. Mammoths last walked the Earth roughly 4,000 years ago, and it is estimated that as many as 10 million carcasses lie frozen under the Arctic Circle.

Melting permafrost in the Siberian tundra has uncovered preserved mammoths, which are legally sold, but conservationists are concerned that smugglers are passing off illegally-traded elephant ivory as mammoth tusks to avoid detection.

Douglas MacMillan, a professor of conservation and applied resource economics at University of Kent, has argued that banning the mammoth trade would actually increase demand upon genuine elephant tusks.

Writing on the website IFLScience, Macmillan says: “A recent analysis linked with empirical data predicts that the 84 tonnes of Russian mammoth ivory that was exported to Asia on average per annum over the period 2010-12 would have actually reduced poaching of wild elephants from 85,000 per year to around 34,000 elephants per year, primarily by reducing elephant ivory prices by about $100 per kg.”

Worries about the potential impact of the mammoth ivory trade has led India and the US states of New Jersey, New York, California and Hawaii to ban the sales of mammoth tusks altogether. As well as the potential risk to elephant populations, paleontologists are concerned that science is losing valuable information from tusks that are sold commercially are never taken into the laboratory.

Speaking to National Geographic, Daniel Fisher of the University of Michigan said: “There’s still important questions to be solved about woolly mammoths. Do we study the tusks and learn something from them, or do we carve them?”

For those species still alive today, gathering accurate data on the viability of the populations remains a difficult task, as does striking a sustainable balance between centuries-old traditions and conservation efforts.

“The Inuit are quite misunderstood by much of the western world,” says environmental consultant Tanya Shadbolt.

“They have a much closer relationship with wildlife and the environment that people who live in cities. They are often portrayed as animal-killers and people who don’t care about the wildlife which is not the case at all”.

“It’s about finding a common ground and working towards that rather than fighting each other over it”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments