The Mauritanian on life in Guantanamo: ‘When you hit rock bottom you have nothing to lose’

Mohamedou Ould Slahi spent 14 years in Guantanamo Bay simply for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. As the adaptation of his diary is released on Amazon Prime, he speaks to Stephen Applebaum about what the film gets right, what it gets wrong, and what life was really like in the world’s most notorious prison

I really love the saying, ‘Democracy dies in darkness’,” says Mohamedou Ould Slahi, as the Zoom connection from his home in Mauritania cuts in and out.

We’re talking about the 50-year-old’s hope that a review of the notorious US military prison at Guantanamo Bay, announced in February by US president Joe Biden’s administration, will generate a debate leading to its closure, and to a resolution for the 40 remaining prisoners, most of whom have been stuck in legal limbo for nearly two decades. Six have previously been cleared for release by the government, but still languish in jail.

“I’m sure if there is a debate, Guantanamo Bay must be closed,” he says. “And it should be closed, because it does not belong in a democracy.”

Slahi was himself a prisoner and a victim of extreme torture at the facility. Plunged into a Kafkaesque nightmare on the back of wild – and never proven – allegations of involvement in terrorism, the computer technician was “kidnapped” from his homeland in 2002 and taken to a prison in Amman, Jordan, where he was held for seven and a half months in isolation. He was later transferred to the US airbase at Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan, by the CIA where he became prisoner 760 before finally being flown to Guantanamo, as part of a group of 34 detainees. After 14 years and two months, on 16 October 2016, he was released without charge.

Read more:

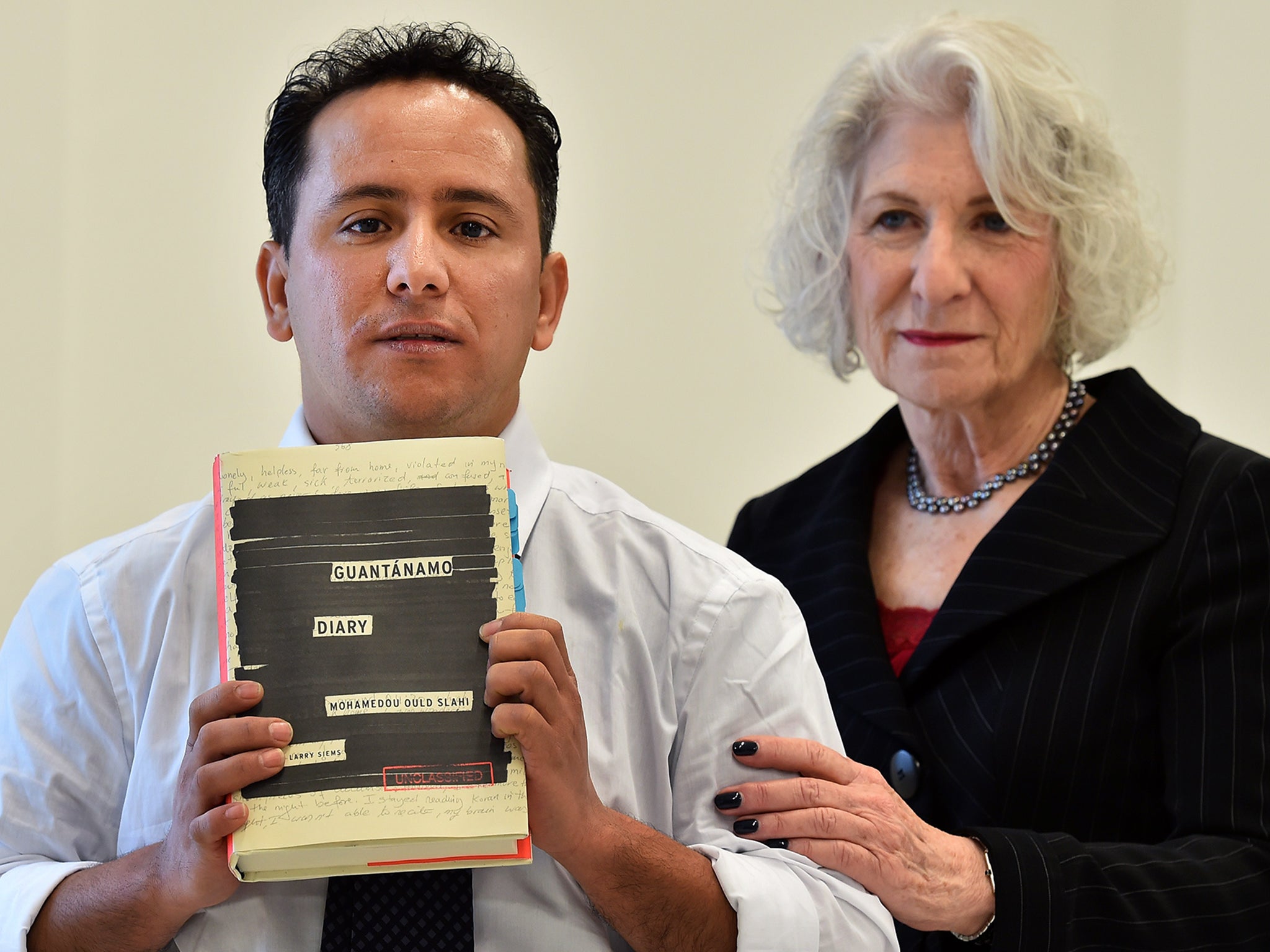

During his incarceration, Slahi wrote a bestselling book, Guantanamo Diary, which has now been turned into a lean and intelligent feature film, The Mauritanian, by The Last King of Scotland director Kevin Macdonald, with A Prophet’s Tahar Rahim as Slahi and Jodie Foster as his lead lawyer, Nancy Hollander.

Although surprisingly missing from this year’s Oscar nominations – the film has been nominated for five Baftas and a Critics’ Choice Award – Slahi is optimistic that The Mauritanian can play a role in helping to pierce the gloom of official secrecy and censorship that still surrounds Guantanamo Bay, and shine a light on what can happen when a government is “the judge and the jury at the same time”.

“To this day, the United States of America is not coming clean about these war crimes and everything,” he says. “How can they keep speaking about China violating human rights? This is good to say, but you have also to show that you’re honest about this stuff, that you really mean it. And you cannot convince anyone that you really mean it when you put people in prison without trial and without due process.”

The prisoners have no public voice of their own, therefore it has to come from elsewhere, he says.

“Everything is classified. Everything a detainee says is classified. Detainees cannot talk to you. They cannot talk to anyone. They cannot challenge, in a meaningful way, their detention. All that is left is for people who survived Guantanamo Bay to speak for people who are left behind, and speak for those who are in so many Guantanamos, plural, in my part of the world.”

The Obama administration tried to close the prison, but was frustrated by the political and legal obstacles ranged against it. When Donald Trump took office, he reversed his predecessor’s desired direction of travel and signed an executive order to keep Guantanamo Bay operational. Is Biden the man who’ll finally get the job done?

“I function on hope,” says Slahi, who knows what it feels like to have nothing else. He also knows what it feels like to be in pain, and recognises in the new president a man who has experienced great loss, and someone whom he believes capable of looking at other people’s agony through the prism of his own trauma.

How can they keep speaking about China violating human rights? You cannot convince anyone that you really mean it when you put people in prison without trial and without due process

“He knows what suffering means,” he says. “He lost his wife [and infant daughter in a traffic collision] when he was very young, and he lost his son [to brain cancer]. I can’t imagine the pain of burying your own son. This is so much pain, it is beyond me. Even just thinking about it makes me dizzy. So, if you know that, you can’t ignore that people are suffering without trial and without being charged with any crime.”

Almost five years after his release, Slahi has still not received an official apology, nor an admission of responsibility, from the United States. Yet despite the years stolen from him, and the psychological and physical torture he was forced to endure, Slahi says he has forgiven everyone. “Everyone who tortured me and kidnapped me, who imprisoned me, I have forgiven everyone. And I wish them, from the bottom of my heart, the best of lives.”

Nevertheless, he admits that the “pain and the suffering” are hard to forget, and it seems clear that the past is still an open wound. “Many nights I wake up not able to breathe,” he says. “I think I’m in Guantanamo Bay. I’m crying and shouting and making it very hard for the people that are with me in the room to sleep.”

Born in 1970, in Rosso, on the Senegal River on Mauritania’s southern border, Slahi was a bright child who went on to become the first member of his family to attend university after winning a scholarship from the Carl Duisberg Society to study in Germany. He enrolled in an electrical engineering degree, but briefly stepped back from his studies to join the fight against the communist-led government in Afghanistan. In 1991, he pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda (before it turned on America), and in 1992 enlisted in a unit that was laying siege to the city of Gardez. When Kabul fell and, Slahi has said, “the Mujahideen themselves started to wage jihad against themselves”, he returned to Germany to finish his degree. Ultimately unable to secure permanent residency, Slahi took a friend’s advice and applied for landed immigrant status in Canada.

Little did the Mauritanian know then that events unconnected to him and the choices he was making were starting to turn him into what a US colonel would later describe as a Forest Gump-like figure who was in “different places that look suspicious, and that caused [the American intelligence services] to believe that he was a big fish, but then when they really invested the effort to look into it, that’s not where they came out.”

Slahi decided to return to Mauritania in January 2000, and while passing through Dakar airport in Senegal, found himself pounced on by police and cuffed. He was taken to a room where a Senegalese interrogator, seemingly under orders from a US intelligence officer, questioned him about any association he might have with Ahmed Ressam, who had been arrested in December crossing into the United States from Canada in a car packed with explosives, for an attack on Los Angeles International Airport on New Year’s Day 2001, in what would become known as the Millennium Plot.

He didn’t know Ressam, Ressam didn’t know him, but the Americans were desperate for information and scalps, and continued questioning Slahi in Nouakchott, Mauritania. On 19 February 2000, the FBI team who’d arrived to interrogate him five days earlier left empty handed, and he returned to his regular life of family and work. Slahi’s problems, however, were only just beginning.

Over a year later, in the aftermath of 9/11, he was again detained by the Mauritanian authorities and questioned by the Americans, who appeared bent on framing him as the mastermind of the Millenium Plot. They’d later also try to tie him to the attacks on the Twin Towers.

This interrogation was “like open season”, recalls Slahi. “They brought a German translator to make sure the communication was right. They wouldn’t introduce themselves, but this [Mauritania] is not a country where they’re respecting rights, you need a lawyer, they read Miranda Rights. No, he hit me. He had a very large bottle of water that he threw in my face.”

Slahi assumed the man was either CIA, FBI, or military: “He felt free to do whatever he wanted without the shackles of the law. And my records were given to him right away. I explained everything to him and they released me.”

A statement was made to the media by the directeur de la Surete de l’Etat affirming Slahi’s innocence, which should have been the end of it. Around a month later, however, while visiting his mother, two secret police barged their way into her house and told him he must attend a meeting with the director general. Slahi was told to drive himself to the jail he knew intimately from previous interviews, as he would probably go home the same day. When he wasn’t interrogated, though, he began to fear the worst.

“They just put me in a room and they closed the door. And I was so humiliated, and was so used to humiliation and used to my rights being violated in my own country, that if I’m not interrogated, I’m concerned,” he says of his emotional state at the time. “I need to be interrogated. I have no dignity. I have no, like, sovereignty, because I’m a Mauritanian citizen. I am from Africa. I am from the Middle East. I have no rights. I need to be interrogated. I owe it to the government to interrogate me, you know? I was so scared.”

His family didn’t know where he was, and were still kept in the dark when, eight days later, on 28 November 2001, Mauritanian Independence Day, Slahi was informed that he was going to be taken to Jordan at the request of the United States, breaking the Mauritanian constitution’s prohibition on extraditing criminals to other countries. The fact that Slahi had already been declared innocent only compounded the injustice.

They just put me in a room and they closed the door ... because I’m a Mauritanian citizen. I am from Africa. I am from the Middle East. I have no rights. I need to be interrogated. I owe it to the government to interrogate me, you know? I was so scared

“I just lost it,” he says. “They wanted me in Jordan and I knew this was a very evil plan because they want to torture. And because America is a holy land, you cannot torture people there; you have to put them somewhere else for torture. So, I have been tortured by my own people, and this is so horrible. There is no good thing in it. It was like being taken to your execution and you are still alive and aware of everything.”

Slahi was kept in isolation, unable to see anyone. Days and nights passed without him knowing. “It was all bad,” he says. “All bad.” After months of interrogation, he was taken to Bagram for two weeks for further questioning, before being bundled onto a military plane on 4 August 2002, and relocated to Cuba. During the flight, he wrote in Guantanamo Diary, he was deprived of hearing and vision by a headset that gave him a “painful headache”, and “ugly, thick, blindfolding glasses”. Chains cut into his ankles while a belt, drawn so painfully tight that he could not breathe, fastened him to a seat. “I felt I was going to die,” he recalled.

As a child, Slahi had developed a “minor compulsion” for writing, and as early as 2003 began to record his Guantanamo experiences in a nascent version of the diary. It was a way of taking some control back. “When the United States government arrested us they started a narrative around me,” he says. “They started to say who I am and what I am, and I didn’t like it because they kept on saying, ‘You’re a bad guy,’ and I was like, ‘Hold on, that’s not me, man. Why are you saying that?’ I wanted to put a hole in their narrative and tell the world this is who I am.”

He wasn’t just doing it for himself but also for his family: “Just think of the very great dishonour to them to have the person whom they, like, raised to be a good guy, involved in killing innocent people. This is horrible.”

Staying true to his identity became Slahi’s “biggest fight”. He was determined that whatever happened, he would not become the caricature the United States was trying to turn him into. “I said, ‘Go f**k yourself. I am not going to be like this guy with a very big beard,’ although I respect people with beards, and say, ‘America is evil’, in a very bad accent.” I can hear his anger building. “I don’t accept this caricature because I am an open-minded Muslim. I respect all religions. I respect all orientations. I respect all backgrounds. But they wanted me to be a crazy person? I was not going to do them that service.”

At first he wrote in Arabic, French and German, jotting down whatever came to mind. He was writing in secret, though, and when his notes were discovered, everything was taken away. Two years later he got a second chance, thanks to a Supreme Court judgement allowing Guantanamo detainees to challenge their detention in habeas corpus proceedings in US courts.

Before meeting his lawyers, Nancy Hollander and Sylvia Royce for the first time in June 2005, “I saw a window and started writing very quickly my story, because I didn’t know when this opportunity was going to close.” The women encouraged him to keep writing, which eventually led, after much legal wrangling, to a redacted version of Guantanamo Diary being published in January 2015 (an uncensored edition appeared two years later).

The arrival of the legal team made Slahi feel “elated”. “When you hit rock bottom, you have nothing to lose,” he says. “When they came to me, after four years, I had been interrogated by so many intelligence services from so many countries. And the United States, they did everything they wanted. There are no shackles on them. So, they were the first American civilians I ever met in my life, and it was like meeting my family.”

By this time, Slahi had been through a living hell. In December 2002, defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld had personally signed off on a “special interrogation plan” that would expose the Mauritanian to months of mental and physical torture. Leading the team responsible for administering it was Richard Zuley, a Chicago detective whose impressive success rate had largely rested on confessions extracted from suspects using brutal interrogation techniques, which he magnified, intensified and imported to Guantanamo.

“He was a contractor because of the great job he did in Chicago, in a negative sense,” says Slahi. “He used to torture people, especially black people, and force them to confess to crimes they didn’t do. Some of them spent more than 20 years in prison. And he came, like the good example, and he broke me with torture.”

Slahi was subjected to extreme isolation, freezing cold, 24-hour shift interrogations, sexual assault, beatings, deafening music, death threats, prevention of religious practices, a punishing and disorientating speedboat trip during which he was forced to drink salt water, sleep deprivation for 70 days, and more.

In Guantanamo Diary, he tells us: “You, Dear Reader, could never understand the extent of the physical, and much more the psychological, pain people in my situation suffered, no matter how hard you try to put yourself in another’s shoes.” I ask if the film gets us closer than the written word.

You, Dear Reader, could never understand the extent of the physical, and much more the psychological, pain people in my situation suffered, no matter how hard you try to put yourself in another’s shoes

“I don’t think you can convey in writing or in a feature film the pain and suffering of 70 consecutive days without sleep,” he says. “Day in, day out, day in, day out. And they used to say, ‘No sleep for terrorists,’ whatever that word means. Because in my part of the world, it means political dissent. If you are not with the government, you are a terrorist. That means your family can be put in prison – and the whole world is applauding.”

Slahi says he “tried to negotiate my way out of torture so many times”. He knew that he wouldn’t be the same after, and tried to convince an intelligence officer to tell him why he’d been kidnapped and why he was being held, so that he could cooperate. “I told her, ‘If you decide to torture me, you will get another person who is not me. You are going to be talking to someone else.’ I was very aware of that.”

He wrote Zuley a false confession which, ironically, says Slahi, was the operator’s “undoing”. When Colonel Stuart Couch (played by Benedict Cumberbatch in The Mauritanian), the marine assigned to prosecute Slahi, realised that it had been obtained under extreme duress, the evidence fell apart. “The thing is, they wouldn’t release me even when they found out I’m innocent.”

Had he seen too much? “That’s the only explanation. They thought I would tell Arab people what happened, and that this is a whole operation of America and they don’t want anyone to know about it, and I was a victim.”

Before he was tortured, Slahi’s impressions of America had been shaped by TV shows such as Married with Children and Law and Order. In his mind, Americans were “funny people and they respect the law”, he says. “But that image was crushed when I was tortured.”

He still wanted to believe in the possibility that America had made a mistake and that it was now going to “get back on track”. “I thought, ‘They have this badass lawyer, they’ll go to trial with the case, I will get released, go to America, get compensation, and everybody is going to be happy and I will live happily ever after.’” It didn’t work out that way.

As shown in The Mauritanian, Slahi was granted a release order by a federal judge in 2010, but the Obama government pushed back and appealed, and Slahi wasn’t released for another six years. What must that period have been like, knowing that he had already been granted his freedom once?

“It was painful,” he says. “I was exposed to a lot of aggression when I won my case. The FBI, and especially the FBI, they’d asked me to cancel the court order because the court order also ensured they could not interrogate me any longer. They said, ‘If you accept it, we will make your life very difficult in prison.’ They took my stuff, my books, everything. They gave some of it back when I maintained my refusal to cancel the court order, but it was hard. Very hard. It was insult to injury.”

Read more:

Life didn’t return to normal when he landed back in Mauritania. Although his liberty had been restored, some of his rights were withheld in an agreement between the United States and his government. In 2019 he was refused a passport to travel abroad for medical treatment and visit family in Germany, and to this day, he says, “I am never allowed to visit the United Kingdom to participate in the promotion of my movie and my books.”

Listening to Slahi speak, you get the sense that he still feels trapped. “What is so disconcerting is when the United Kingdom wants information about a citizen from this part of the world, do you know what they do? They ask the local government what they think about that citizen. And based on that information, they classify that person as an enemy or a good guy. This is so insulting to our dignity.”

“This is why I am dedicating the rest of my life to human rights and the rule of law in this part of the world,” he says. “It’s enough. We need to have the same freedom that people enjoy in Europe.”

‘The Mauritanian’ is available to stream on Amazon Prime

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments