The Village Voice sings no more: after 62 years the alt-mag is closing

The closing of the venerable weekly magazine The Village Voice marks the end of an era, says David Barnett, not just for the much-loved publication, but for the idea of an alternative press

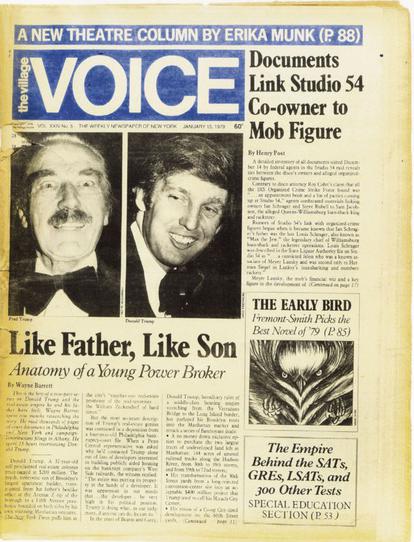

Everything is alt, these days. Nazis seek to shrug off the baggage of their old labels by re-branding themselves the alt-right. Balance, of course, dictates there must be an alt-left — Donald Trump thinks so, but some of those he slaps that sticker on think there’s no such thing. For years we’ve had alternative rock — alt-rock, of course, especially in the US, though we’d be more likely to call it “indie” in the UK — and even alt-lit.

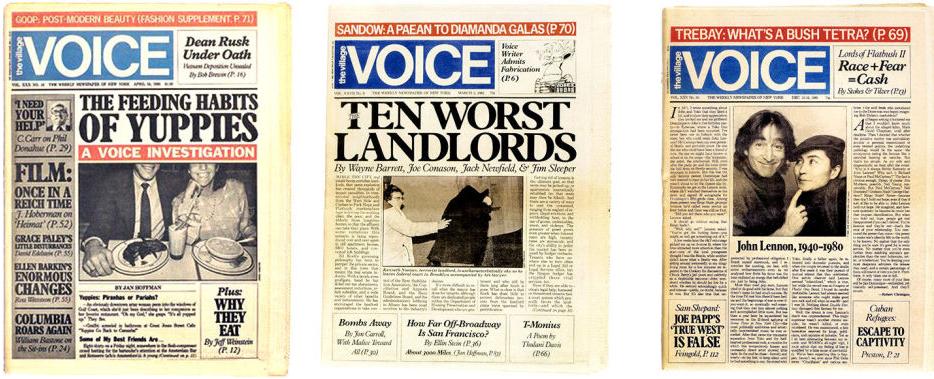

Alt is experimental, pushing boundaries, railing against the mainstream and the traditional. And so it’s been for 60-odd years with the alt-weeklies. That's another Americanism of course; we might easily use terminology such as the full name alternative, or independent, or even underground, to describe the once-proliferating periodicals that provided something different from the established news organisations who might have been in existence, in some cases, for hundreds of years. And now the granddaddy of the alt-weeklies, The Village Voice, is shutting up shop — well, in print form at least.

The weekly’s current owner, Peter Barbey, said in a statement this week: “For more than 60 years, The Village Voice brand has played an outsized role in American journalism, politics, and culture. It has been a beacon for progress and a literal voice for thousands of people whose identities, opinions, and ideas might otherwise have been unheard. I expect it to continue to be that and much, much more. ”

The Village Voice will turn 62 in October, having launched in 1955. It has the distinction of being the first of what became known as the alt-weeklies, many more of which sprung up in its wake. They were less focussed on breaking news and parish pump issues of the traditional local papers; leaning more towards arts, culture, commentary and progressive opinions. Alt-weeklies were nearly always left-leaning. The Village Voice was founded by Norman Mailer, Dan Wolf and Ed Francher, and run out of a small apartment in New York’s Greenwich Village, the counter-cultural capital of the Big Apple.

The Voice perhaps bridged the gap between the existing, traditional media available at the time and the avant-garde, more literary-focussed magazines that arose in the white heat of the Beat Generation years such as the Evergreen Review, which launched a couple of years later and which featured work from the likes of Jack Kerouac, Bertolt Brecht, Albert Camus and William S Burroughs. But the real alt-revolution took place over many years far away from the cultural hotspots of New York and San Francisco. And in recent years they’ve played a vital role to towns and cities which have seen their traditional media scaled down or even closed as the big corporations put profitability over serving local communities.

Alt-weeklies like the Arkansas Times, which was set up in 1991 by staffers who lost their jobs when media company Gannet closed the Arkansas Gazette. The Boise Weekly, founded in 1992, and distributing 35,000 free copies every Wednesday. The Maine Edge, the Portland Phoenix, the Anchorage Press. The Association of Alternative Newsmedia (AAN) was set up in 1978 to offer services and support to this burgeoning new media; today it represents 108 publications across the US, which it says have a combined reach of 38 million readers in print and online.

According to the AAN: “There are a wide range of publications in the AAN, but all share these attributes: an intense focus on local news, culture and the arts; an informal and sometimes profane style; an emphasis on point-of-view reporting and narrative journalism; a tolerance for individual freedoms and social differences; and an eagerness to report on issues and communities that many mainstream media outlets ignore. AAN members speak truth to power. ”

Britain has never had an alternative press on the scale of the US, of course, and a lot of that is probably to do with the sheer geographical size of America, and the fact that if your local paper in Arizona is closed down, there’s no alternative for literally hundreds of miles. The closure of local papers in the UK continues apace; according to research from the Media Reform Coalition published at the end of last year there had been almost 200 closures since 2005. But proper alt-weeklies have rarely sprung up in their place, not in the style of the arts-led American versions.

We have success stories such as the Hackney Citizen, a free independent monthly which is more in the model of a traditional newspaper, and we get the proliferation of A5 glossy magazines which drop through my door on an infrequent basis and which usually have some variation on “Local Life” in their title. These latter products certainly fit the bill of being hyper-local, often targeted at specific villages or communities. Some of the writing isn’t too bad. But they really excel in providing advertorials for local businesses, verbose paeans to the neighbourhood plumber or prom dress purveyor, which neither offers much in the way of actual journalism and — through undercutting the slow to react mainstream media — is ultimately hastening the demise of the local papers through death by a thousand revenue falls.

We’ve had our alt-press moments in the UK, of course. Time Out began as a proper underground weekly in 1968, but by 1980 had abandoned its radical roots — including collective editorial decision-making and a commitment to equal pay — which led to some staffers walking out and founding the similar City Limits under the original principles. Time Out is still a force to be reckoned with in London, New York and Hong Kong, a mainly listings magazine given out free and which competes with newcomers in that market such as Stylist and the recently-repositioned former music weekly colossus NME.

City Limits, after many successful years as a proper alt-weekly, went through a flurry of ownership changes that saw it put to sleep in 1993. Ultimately, why should we care? The Village Voice is ending as a printed artefact but will continue as an online magazine. Isn’t that all we can expect in this internet age? After all, this piece is being written on a laptop and will be emailed to The Independent, who will publish it in their dedicated Daily Edition App and on their website. You will read it on your phone, your tablet or your laptop. No trees will be harmed at any stage of the writing, publication and reading of this article.

But while even I, who have had ink running through my veins since I was 19 years old, have embraced the idea of online news, there still seems something about the alternative press that demands some sort of physicality. A couple of years ago, the New York Times ran an op/ed piece entitled Are Alt Weeklies Over? It was written by Baynard Woods, the editor of the Baltimore City Paper, an alt-weekly which it had just been announced was being taken over by the Baltimore Sun Media Group, and posited a bleak future for the alt-weeklies.

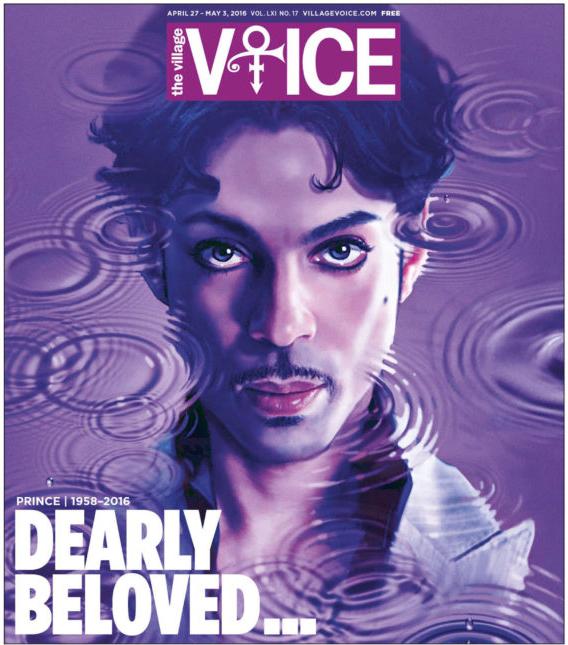

“This glum outlook is understandable after the recent demise of venerable alt weeklies like The Boston Phoenix, which closed last year, while standard-bearers like The Village Voice have fired many of their most popular writers,” wrote Woods. “Many have been bought by corporate conglomerates, then thinned out and tamed. Not that we get much sympathy: For many people, the alt weekly as a genre is already passé, rendered irrelevant by the rise of the Internet.

“But an alt weekly is connected to a city in the way that a website can never be. In Baltimore, somewhere between 20 and 40 per cent of the population doesn’t have regular Internet access. The glib techno-utopians who not only foresee a paperless tomorrow, but also lobby for a paperless present, are ready to forget about these people. Alt weeklies might not always reach everyone in the city, but at least, like the dailies, they try to be available and relevant to everyone.”

Like their mainstream counterparts, the alt-weeklies offer a measure of brand recognition and trustworthiness grown over many years. Yes, they might well extend these brands online, but unless you have an ultra-strong recognition factor and ease of access — like, for example, The Independent — then there is a risk of getting lost among the welter of information, misinformation, and disinformation that is the internet. We know we can be less discerning when we browse the web for news or comment, we can fall down a rabbit hole and end up in places that offer opinions but no facts; worse, even fake news or unsubstantiated half-truths and suppositions.

For those of a liberal bent who had a healthy distrust of their local mainstream media publication, the alt-weeklies provided much of the same trustworthy content but free of corporate entanglement. It’s perhaps sadly inevitable the alternative press will go the way of the mainstream media as we turn our backs on print, and The Village Voice is only the latest, if the most high-profile, example of this.

Still, you can never write off the seemingly innate human desire to craft, and create, and make a lasting artefact, nor the drive of grassroots communities. With the rise of the alt-right, perhaps the alt-weeklies and their left-leaning outlook will be given a fresh impetus, and who knows? The decline might not only be arrested, but reversed. Just maybe, the resistance starts here.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments