How The Beatles tried to escape the 'rat's nest of fame' in India

Kai Schultz recalls the Fab Four’s eventful trip to the ‘madman’s camp’ and finds the buildings gently weeping

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

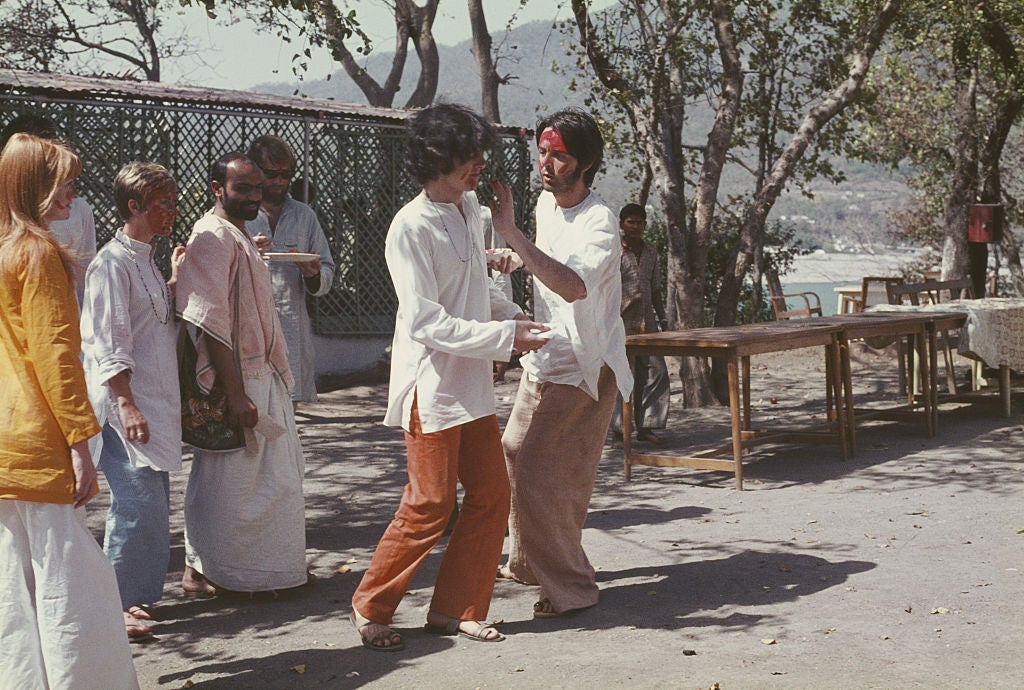

Your support makes all the difference.In 1968, The Beatles and a crew of hangers-on traded hip London threads for kurtas and wreaths of marigold, trudging through dense forest to an ashram in Rishikesh, India, where they spent weeks writing songs.

There was George Harrison, a devoted follower of Transcendental Meditation; John Lennon and Paul McCartney, who had started to feud over the band’s direction; and Ringo Starr, the band’s drummer, who was so perturbed by India’s famously spicy food that he packed a reserve of beans for his stay at the ashram. He lasted 10 days.

“Scan all the photographs of Ringo in Rishikesh, and you’ll find few in which he’s smiling,” says Raju Gusain, a local journalist who has become something of an expert on the band’s trip to India.

These days, the forest has swallowed up the ashram’s crumbling buildings, obscuring traces of celebrity from their halls. But the complex is set for a revival, with renovations planned for many of the structures, long unused and only recently reopened to the public.

A new museum on the grounds will showcase the legacy of The Beatles and Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the guru whom band members abruptly fell out with towards the end of their stay in Rishikesh. Across the world in Liverpool, The Beatles Story, a museum dedicated to the band, is opening an exhibit next month to mark 50 years since their trip to India.

Over the years, as more spiritual seekers from the West travelled to India looking for enlightenment, Rishikesh ballooned in size. But when The Beatles arrived, the place was a sleepy town straddling the banks of the Ganges.

Bob Spitz, a biographer, characterises the trip as a spectacularly creative time for the band, and as an escape from the “rat’s nest of fame” that consumed their lives in London.

With noise from the big city far behind them, Lennon and McCartney wrote many of the songs that would later appear on The Beatles (the White Album), including “Back in the U.S.S.R.” and “Dear Prudence”. Of note, Spitz says, was a brief thaw in the deteriorating relationship between the men.

“The pressure of being The Beatles had driven a wedge between them individually and that had all percolated in the months leading up to their visit to Rishikesh,” he said. “Once they got there, and they unburdened themselves from all of that, they reconnected with their songwriting and their creativity. It just flowed forth.”

A few months before the trip, George Harrison, who had discovered the sitar and Hinduism, brokered a meeting in England between the band and Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the progenitor of Transcendental Meditation, which involves sitting and repeating a mantra silently.

Eventually, the rest of the band agreed to a trip in February 1968 to visit the Maharishi’s ashram in Rishikesh, recruiting their wives, girlfriends and an entourage that included Mia Farrow, Donovan and Mike Love of The Beach Boys, among many others. The band, Harrison said, was “looking to re-establish that which was within”.

Though most days at the ashram were spent engaged in simple pursuits like meditating and writing, the grounds were not exactly spartan. The Maharishi’s cliff-side bungalow, where the band would gather for lectures (and the occasional argument) had a nearby helicopter pad, and living quarters were equipped with electric fireplaces.

In the evenings, the group would sometimes break the ashram’s no-alcohol rule with “a glass of hooch” smuggled in from a nearby town, Cynthia Lennon, Lennon’s wife at the time, wrote in her memoir. “Giggling like naughty schoolchildren, we’d pass the bottle around, each taking a swig, then contorting as it scorched its way down our throats,” she said.

Today, many of the original buildings have been demolished, but a few unmarked structures from 1968 still stand, says Anand Srivastava, the Maharishi’s nephew, who had helped manage the ashram for many years.

These buildings include the post office where Lennon waited for letters from Yoko Ono and the Maharishi’s crypt-like sleeping quarters, now inhabited by bats. A set of 84 blackened meditation caves also survived.

The ashram remained operational for many decades after the band left, housing dozens of straight-backed sadhus, or holy men, in small domed huts. But in the early 2000s, the land was taken over by the Indian government, leading to its abandonment, except for wandering leopards and elephants from a nearby nature reserve. In 2008, the Maharishi, who had moved to Europe, died.

By the time the ashram was reopened to the public in 2015, part of a campaign to draw tourists to the area, most of the buildings had been vandalised by young lovers, who had hobbled over broken security walls to scrawl sweet nothings, and the occasional phallus, on the mildewed walls of remaining structures.

An industrial, open-air building nicknamed “The Beatles Cathedral Gallery” was also co-opted by an artist’s collective and filled with hundreds of quotes from the band’s songs.

Tourist numbers are still low, with around 13,000 people, mostly Indians, visiting the ashram last year. But Macarena Arraez, 30, from Spain, appears excited when asked about the planned renovations, saying the ashram had great potential for raves and fashion photo shoots.

Relaxing outside the meditation caves, Arraez has spent part of the morning meditating, and the experience has left her overwhelmed. “I was looking for the most spiritual place in the world and that’s what I found,” she says.

Down below the ashram, yoga institutes have mushroomed along the Ganges, where visitors from across the world thumb through books by Osho, smear vermilion on their foreheads and shop for chunks of crystal.

A gluten-free cafe devoted to The Beatles’ music, which overlooks a slab of hills blanketed with mist, also draws steady business.

But long-time Indian visitors say the Rishikesh that existed around the time The Beatles arrived and the one today are hard to reconcile.

Bhuvneshwari Makharia, from Mumbai, who has visited Rishikesh for years, says the rigour of the ashrams and yoga programmes have been gradually diluted to meet the expectations of foreigners looking for a quick cosmic fix.

“If they come, they should come for our culture, not for it to be Westernised,” she says. “We are designing ourselves as per their demands.”

For The Beatles, the connection to Rishikesh petered out. By April 1968, only two band members, George Harrison and John Lennon, were still at the ashram.

A few weeks before they were set to depart, Magic Alex, one of the band’s business associates, spread rumours that the Maharishi had made sexual advances towards a female student, warning them of “black magic” if they stayed at the ashram. The band members abruptly packed their bags and left the “madman’s camp”, Lennon said.

“We sort of feel that Maharishi for us was a mistake, really,” he told an interviewer. “We thought he was something other than he was.”

McCartney added, “There were we, waiting for someone, the great magic man to come.”

Srivastava, the Maharishi’s nephew, denies that his uncle had made any sexual passes, describing him as warm, humble and fiercely committed to his work.

After the band left Rishikesh, different impressions of their time there also surfaced, with Harrison saying there were “a lot of flakes” at the ashram, including members of the band, and Cynthia Lennon questioning the truth of the rumours and the motives of Magic Alex, “whom I had never once seen meditating”.

“I hated leaving on a note of discord and mistrust, when we had enjoyed so much kindness and good will from the Maharishi and his followers,” she wrote in her memoir.

But John Lennon was less convinced at the time, writing his last song in India, “Sexy Sadie”, originally titled “Maharishi”, as a thorny tribute to the guru and the chapter of his life he was leaving behind. “Sexy Sadie, you’ll get yours yet however big you think you are.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments