Beyond bad character: The history of tattoos on Victorian convicts

A recent data-driven study has found that tattoos had myriad associations from expressions of love to substitutes for jewellery. By Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alker

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Thomas Whitton was a labourer and shoemaker from Shoreditch, east London. He was just 13 in June 1836 when he was convicted at the Old Bailey for shoplifting printed cotton. His sentence was transportation to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania).

When he arrived on the shores of Australia a year later, the brown haired, blue-eyed Londoner had acquired some interesting tattoos on his long voyage. On his right arm there was a tribute to a girl with the words “love to thy heart” and on his left, images of two men with a bottle and glass, a mermaid, an anchor and the initials “R.R.”.

Whitton (who was eventually freed at the age of 20) was just one of 57,990 Victorian convicts whose tattoo descriptions we found as we data-mined the judicial archives. At the time, some commentators believed that “persons of bad repute” used tattoos to mark themselves “like savages” as a sign they belonged to a criminal gang. But our database reveals that convict tattoos expressed a surprisingly wide range of positive and indeed fashionable sentiments. And convicts were by no means the only Victorians who acquired them.

These records allow us to see – for the first time – that historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

To study these questions, we carried out the largest analysis of tattoos ever undertaken, examining 75,688 descriptions of tattoos, on 57,990 convicts in Britain and Australia from 1793 to 1925. We used data-mining techniques to extract information embedded within broader descriptive fields of criminal records, and we linked this information with extensive evidence about the personal characteristics and backgrounds of our subjects. Because the meanings of tattoos are often so difficult to fathom, we used visualisations to identify patterns of use and juxtapositions of particular designs.

A brief history of tattoos

Tattooing has taken place throughout human history. Evidence from bodies preserved in ice indicates the existence of the practice as early as 4000BC. And, while it is impossible to trace a continuous history, there is evidence of tattooing in most cultures, sometimes as a form of forced stigmatisation (on slaves and criminals in the Greek and Roman empires) but in many cases as a voluntary practice used to express identity.

Early Christians acquired religious tattoos as a sign of devotion, and to commemorate pilgrimages. Banned by Pope Hadrian in 787, tattooing largely disappeared from recorded history in the medieval west, though we know it was present in many other cultures, notably Polynesia and Japan.

The traditional narrative has it that the practice was resurrected in Europe after Captain Cook and his sailors encountered the tattooed inhabitants of Tahiti on his visit there in 1769. But more recently historians, including Jane Caplan and Matt Lodder, have uncovered evidence of tattoos among soldiers, sailors and labourers in the century preceding Cook’s voyage. The convict records used in our study date from 1793 and so document a practice which was already widespread.

A written record

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.

Similar prison records started being kept in Britain from 1816, in part so that escapees could be identified. But the record-keeping became even more systematic due to growing concerns about re-offending in the 19th century.

Designs and subjects

Contrary to contemporary beliefs, convict tattoos included a wide range of subjects and designs and expressed some very positive emotions.

We found multiple records of images relating to British and American identity as well as designs based on diverse subjects like astronomy, pleasure, religion and sex. Among the most popular were naval themes and expressions of love. But the most popular form of tattoo was written names and sets of initials, which were present in 56 per cent of all descriptions. Dots were also very popular and were found in 30 per cent of descriptions.

Contrary to contemporary beliefs, convict tattoos included a wide range of subjects and designs and expressed some very positive emotions

The distribution of subjects became more even over time, as some popular early themes – notably naval, jewellery and astronomy – declined and there was a rise in tattoos depicting religion, nature, national identity and death.

Up to 1850, the evidence comes primarily from convicts transported to Australia, a quarter of whom were tattooed. Although we can’t be sure, it is likely that most were acquired during the long voyage. The fact that many had their year of conviction or transportation tattooed on their skin reflects recognition of the fact that their forcible removal halfway around the world, probably never to return to Britain, was a life-changing event.

Naval themes and love

Naval tattoos were rich in diversity and included mermaids, ships, sailors, flags and related astronomical symbols like the sun, moon and stars. But the most popular design was the anchor. Sailors, such as Thomas Prescott, transported to Australia in 1819, bore an “anchor, mermaid, heart and darts, sun, moon and stars” on his right arm. Tattoos that expressed relationships with lovers, friends and family were also very popular (probably since the journey to Australia forcibly separated them from their loved ones). These were more often than not worn in visible areas of the body such as the forearms and hands.

Naval tattoos were rich in diversity and included mermaids, ships, sailors, flags and related astronomical symbols like the sun, moon and stars

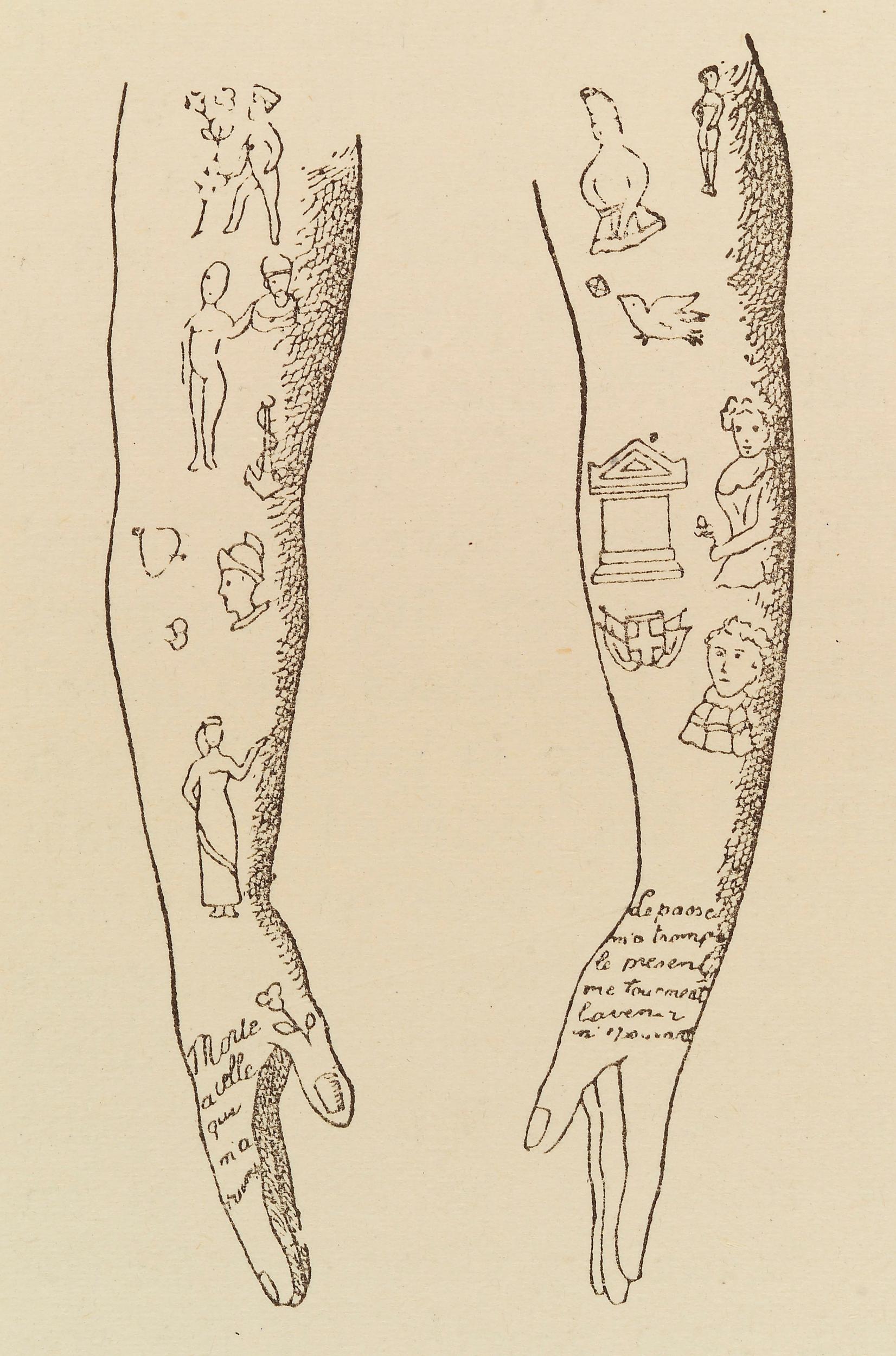

Where first names were tattooed on a convict’s arm, they were much more likely to be names of someone of the opposite sex. The initials “i.l.” (meaning “I love”) often preceded other pairs of initials. A 21-year-old William Graham, for example, was imprisoned in the new national penitentiary, Millbank, in 1826 for “grand larceny”, including the theft of a handkerchief and “pair of breeches”. He demonstrated his love for his family with their initials and those of “E.C.” (probably his lover). He also had a heart and crossed arrows on his right arm. His left arm bore his own initials together with “E.C.” and a “bird in a bush”. This design was depicted in a rare sketch from the prison register.

As is so often the case, we will never know precisely what William intended to express with these tattoos or who E.C. was. But undoubtedly love was involved.

Five dots and criminal identity

In the late 19th century, social observers, criminologists and the press were preoccupied by the notion that tattoos were evidence of “criminal character”. Social investigator Henry Mayhew wrote in his 1862 book on London prisons:

“‘Most persons of bad repute,’ said the prison warder, ‘have private marks stamped on them – mermaids, naked men and women, and the most extraordinary things you ever saw. They are marked like savages, whilst many of the regular thieves have five dots between their thumb and forefinger, as a sign that they belong to the forty thieves, as they call it.’”

There is, however, little to suggest that the tattoos from the time frequently expressed a criminal identity. While there is some evidence of the “five dots” described by Mayhew, the data we found allowed us to debunk this historical myth. In 1828, a series of juvenile thefts in London sparked anxieties about youth crime. The Morning Post complained about:

“A gang of no less than 40 juvenile delinquents ... known as the ‘Forty Thieves’, on all the metropolitan roads, where they subsist by their plunder on the coaches and passengers.”

The “Forty Thieves” could allegedly be identified by their tattoos – five dots worn between their thumb and forefinger: “They recognised each other by five blue spots on the hand, which was made by gunpowder,” claimed The London Standard on 3 January 1829.

Five dots was indeed a popular tattoo, but not primarily in the contexts described by Mayhew and the papers. Our data shows the presence of this tattoo in the 1820s, where it was found on 23 convicts. But while five dots grew in popularity into the 1870s, it was found not only on imprisoned male convicts, but also on those who were transported – especially women. And while convicts were often imprisoned before they were transported, the widespread use of the five dots tattoo (378 convicts between 1820 and 1880) suggests that any “gang” could not have been easily identified by this tattoo alone.

Working-class jewellery

As the simplest tattoo to create, dots were hugely popular: over 20,000 convicts wore one or more dots on their arms, hands and even faces. The left side of the body was dominant, suggesting that dots were often self-administered. But the collocations (designs located alongside the dots on the same part of the body) demonstrate that dots, including five and seven dots, were rarely aligned with expressions of criminality or defiance – such as skull and crossbones – but were often used for purely decorative purposes, like rings and bracelets.

As the simplest tattoo to create, dots were hugely popular: over 20,000 convicts wore one or more dots on their arms, hands and even faces

Such tattoos were a form of working-class jewellery that was cheap and easy to administer. Sarah Phillips, for example, transported in 1838 for stealing boots, wore a “seven dots ring” and “three dots” on her fingers. Other collocations for the seven-dot tattoo included the sun, moon and stars, which likely meant that dots were used to represent constellations, such as the seven-star Pleiades cluster. They could also represent love. Elizabeth Morgan’s recorded marks in the transportation records suggest that she used her five-dot tattoo as part of an expression of love for a Joseph Bayles.

Pleasures and censorship

Rather than expressing a criminal identity, convicts inscribed their bodies in much the same way as today – commemorating their lovers and family, coming-of-age and the pleasures of working-class life. Some 5 per cent of convicts wore tattoos relating to pleasure. Sixteenth birthdays, for example, were commemorated by tattoos of bottles.

Alcohol, smoking, dancing and cards were the subjects of a range of tattoos. James Allen wore a tattoo of a glass and a man smoking a pipe. Among Marion Telford’s nine tattoos was a man and woman dancing on her right arm. Sports were also celebrated.

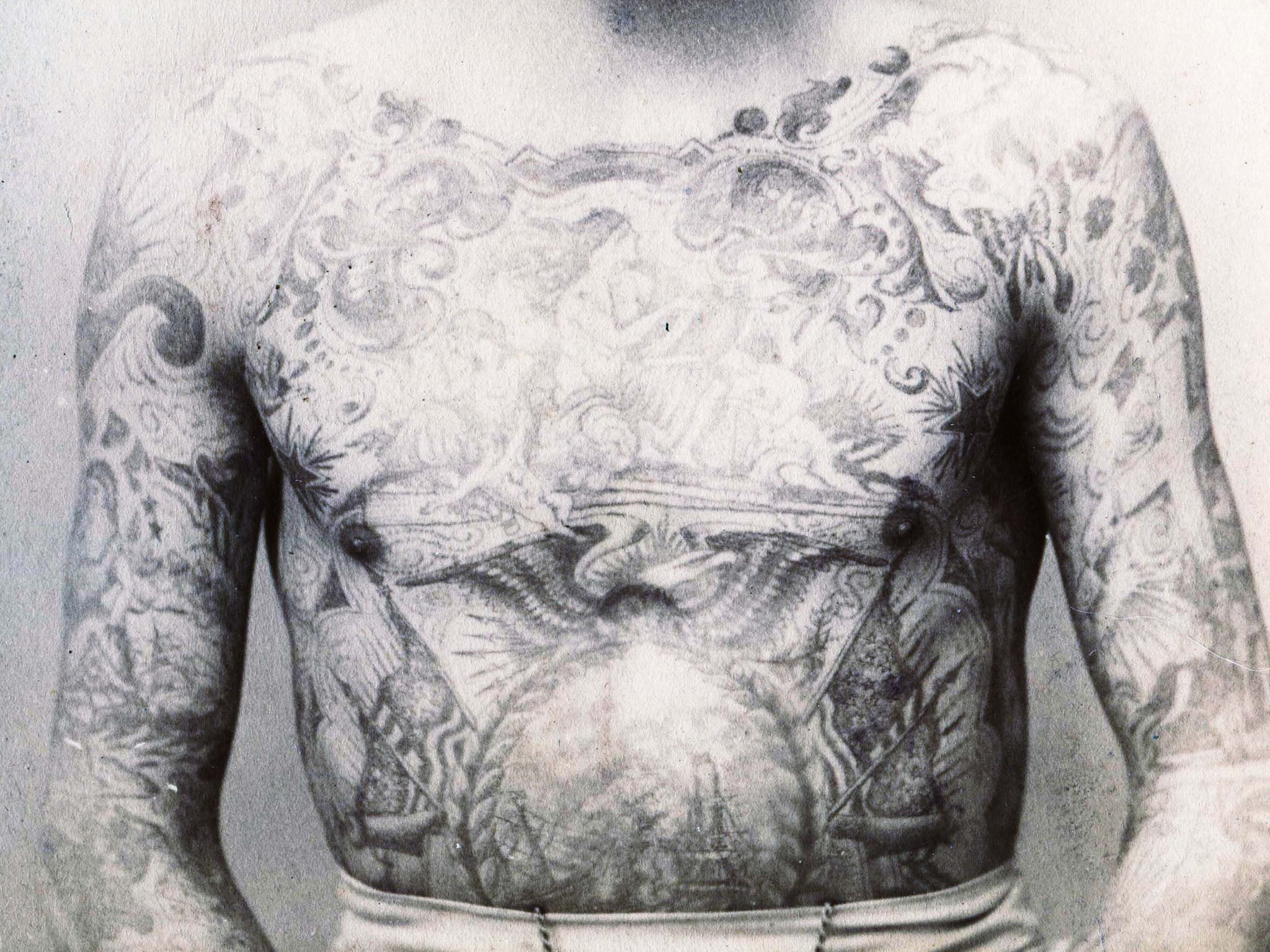

When William Lindsay arrived in Australia in 1854 his body was decorated with a full boxing match on his chest as well as several other distinctive images, including “brig in full sail”, “whale spouting”, “mermaid”, “woman on right arm”, “sailor and flag, snake and three rings”.

Sex was also a theme but Victorian clerks often obscured the level of obscenity from the records, as when part of Robert Dudlow’s tattoo was described as an “indecent word”. But images of naked men and women were tattooed commonly on visible parts of the body.

Convicts also expressed an interest in nature. There were many animals, including birds, butterflies, horses, dogs, snakes and scorpions. Flowers were often worn with animals (especially birds) or were wrapped around the wrist or neck to replicate jewellery. Frederick Ash, convicted in 1889 at the Old Bailey of the rape of a 13-year-old girl, was recorded in the Register of Habitual Criminals in 1893 as having 25 designs on his body. The designs included an elephant, mermaid, “girl on a donkey”, snake, lion and a unicorn (apparently as part of a coat of arms), chameleon, scorpion, another lion and a tree centipede.

A fashion spreads

It is not clear how the fashion for tattooing spread but the evidence suggests that increasing numbers of men and women – not just soldiers, sailors and convicts – acquired tattoos over the course of the 19th century. The birth dates of convicts with and without tattoos in the Register of Habitual Criminals shows a clear increase in the proportion of convicts with tattoos; half of the convicts documented possessed tattoos by the end of the century.

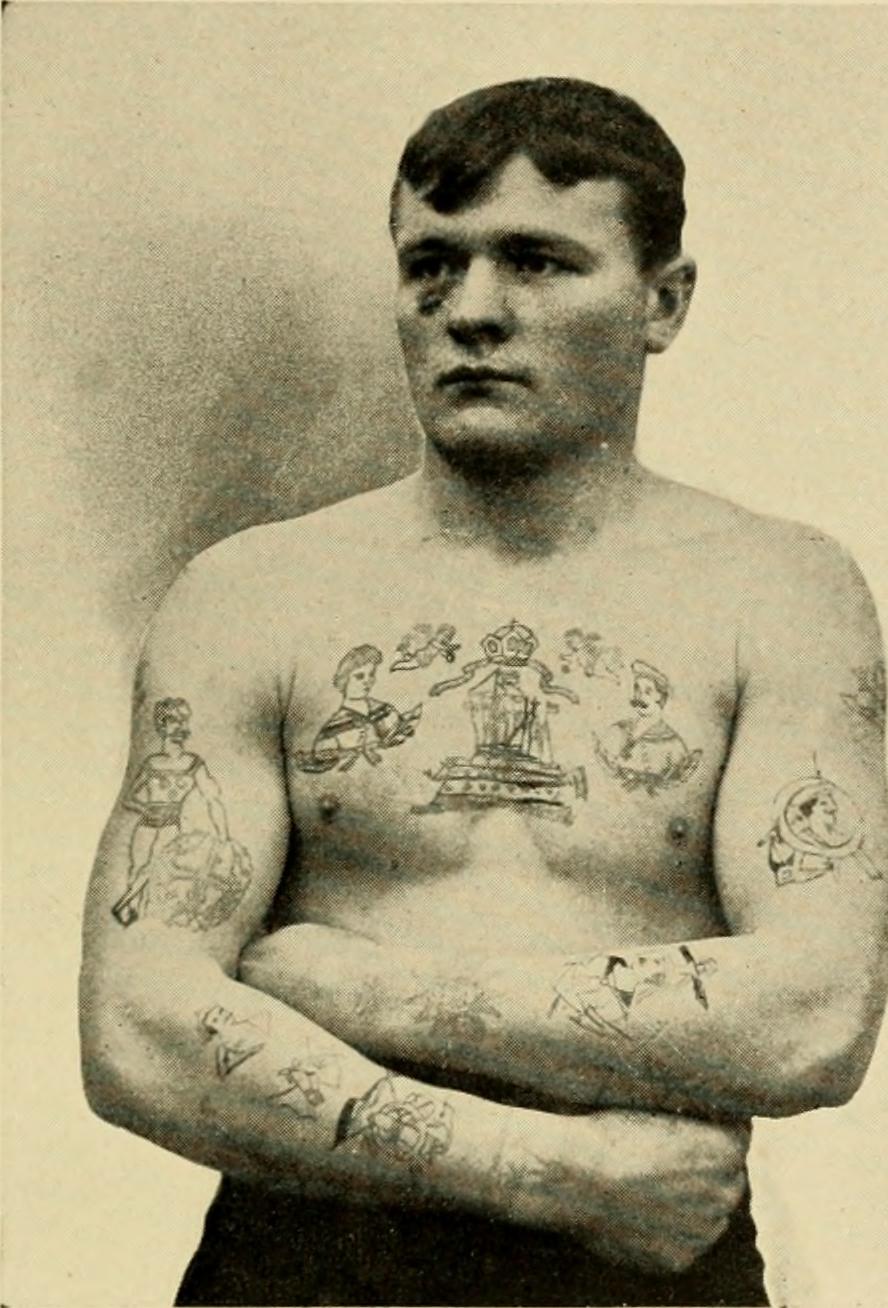

Evidence of tattooing outside the convict record is sparse but there are tantalising suggestions that people from a wide range of social backgrounds acquired tattoos. Alongside the thousands of labourers and unskilled workers with tattoos in our records were 60 clerks, 49 dealers, 22 agents, and 20 engineers. Knowledge of tattooing was spread by the tattooed “freaks” on display in circuses and fairs, and returning sailors and officers from Pacific voyages. There was also the growing publicity accorded to tattoos in print towards the end of the century.

Alongside the thousands of labourers and unskilled workers with tattoos in our records were 60 clerks, 49 dealers, 22 agents, and 20 engineers

Public awareness of tattooing in the 1870s was spread by the widely publicised court case of the Tichborne Claimant, when an imposter (variously referred to as Thomas Castro or Arthur Orton) claimed to be Roger Tichborne, the missing heir to the Tichborne baronetcy. His claim collapsed in 1872 when it was revealed that Roger possessed distinctive tattoos, while Castro/Orton – as our records confirm – had none.

And in the 1880s, a tattooing craze developed in elite society after it became known that various members of the nobility and royalty, both male and female, had acquired tattoos, including Edward, Prince of Wales and Prince Albert Victor, Queen Victoria’s eldest son.

This craze was facilitated by the development of professional tattooists who set up shops, and by the invention of an electric tattooing machine in 1891, by an American, Samuel O’Reilly. By 1900 tattooing had permeated many parts of British society.

Buffalo Bill

Emblematic of the popularity of tattooing at the end of the century are the 392 convicts in the database (all male) who had a tattoo of the American showman, Buffalo Bill. The first tour of his Wild West show in Britain took place in 1887 when he performed for Queen Victoria. His London shows alone attracted 2.5 million customers and he returned for further tours over the next 15 years. It appears that tattooists took advantage of his popularity by developing templates of his image and offering the tattoo as part of the experience of going to the exhibition.

Tattoos of a bust of Buffalo Bill were frequently found on convicts with tattoos of women, a woman’s head and clasped hands – as in Charles Wilson’s tattoos, which included “two hearts (one pierced), clasped hands and an anchor” on his right forearm and a bust of Buffalo Bill and the word MAGGIE in capital letters in a scroll on his left forearm.

The frequent expressions of love associated with Buffalo Bill tattoos suggest that men often went to see the show with their lovers and obtained tattoos to commemorate both the visit and their love for each other. The men who had a Buffalo Bill tattoo included a blacksmith, a postman, a shoemaker, a painter and glazier.

A setting sun

Tattoos became more sophisticated around the turn of the 20th century. William Henry Greenway, a “habitual criminal” who was tried in 1907, worked as a Liverpool photographer. He celebrated his occupation with a tattoo of a camera on his forearm. In 1910, William Parfitt was described as having a tattoo of a propeller on his forearm, as did one of the latest convicts in our dataset, John Miller, who was imprisoned for “housebreaking” in 1924. Combining both traditional designs and modern inventions to commemorate his lost brother, Miller wore a propeller alongside “a setting sun, sinking ship, sailor’s grave, tombstone, in memory of dear brother RT and a pierced heart”.

Convict tattooing was an expressive activity, rarely specifically linked to their crimes and punishments. In their images of vice and pleasure some convicts may have signalled an alternative morality but for most, tattoos simply reflected their personal identities and affinities – their loves and interests. As tattooing became more popular and proficient, it became more inventive and creative, reflecting wider cultural trends and fashions.

But in the early 20th century, as a result of its criminal associations and increasing concerns about hygiene, tattooing lost some of its popularity and became a marginal, though still significant, activity (in particular among sailors and soldiers during wartime). And then from the 1950s, according to sociologist Michael Rees, tattooing started to regain popularity, first among marginal groups including gang members, bikers, and punks and rockers as symbols of both group allegiance and defiance of conventional society.

It was only with the recent tattoo renaissance, dating from the 1970s, that it started to become mainstream, permeating consumer culture through the media and the exposure of tattooed celebrities. It was eventually recognised as an art form. Today, one in five Britons reportedly have a tattoo.

And our research shows that the motivations for getting a tattoo may not have changed much since Whitton first exposed his skin to ink as he sailed for Tasmania more than 180 years ago.

Robert Shoemaker is a professor of 18th-century British history at the University of Sheffield. Zoe Alker is a lecturer in 19th-century history and digital humanities at the University of Liverpool. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments