The brutality of the Syrian regime must be told

More than 95,000 Syrians have ‘disappeared’ since March 2011. Alistair Burt MP, minister of state for the Middle East, introduces Amina Khoulani, who witnessed the regime’s brutality first hand

Have you ever commented online about a government policy, signed a petition or taken part in a peaceful demonstration? Freedom of expression is a fundamental human right, isn’t it?

And now imagine being arrested, tortured and detained for years, simply for this. For the people of Syria, such brutality is part and parcel of the Assad regime.

Over 95,000 Syrians have ‘disappeared’ since March 2011 according to Syrian civil society organisations, of which more than 80,000 are estimated to have been forcibly disappeared by the Syrian regime. The overwhelming majority of these people have been regular, everyday citizens. Many of them have died as a result of torture.

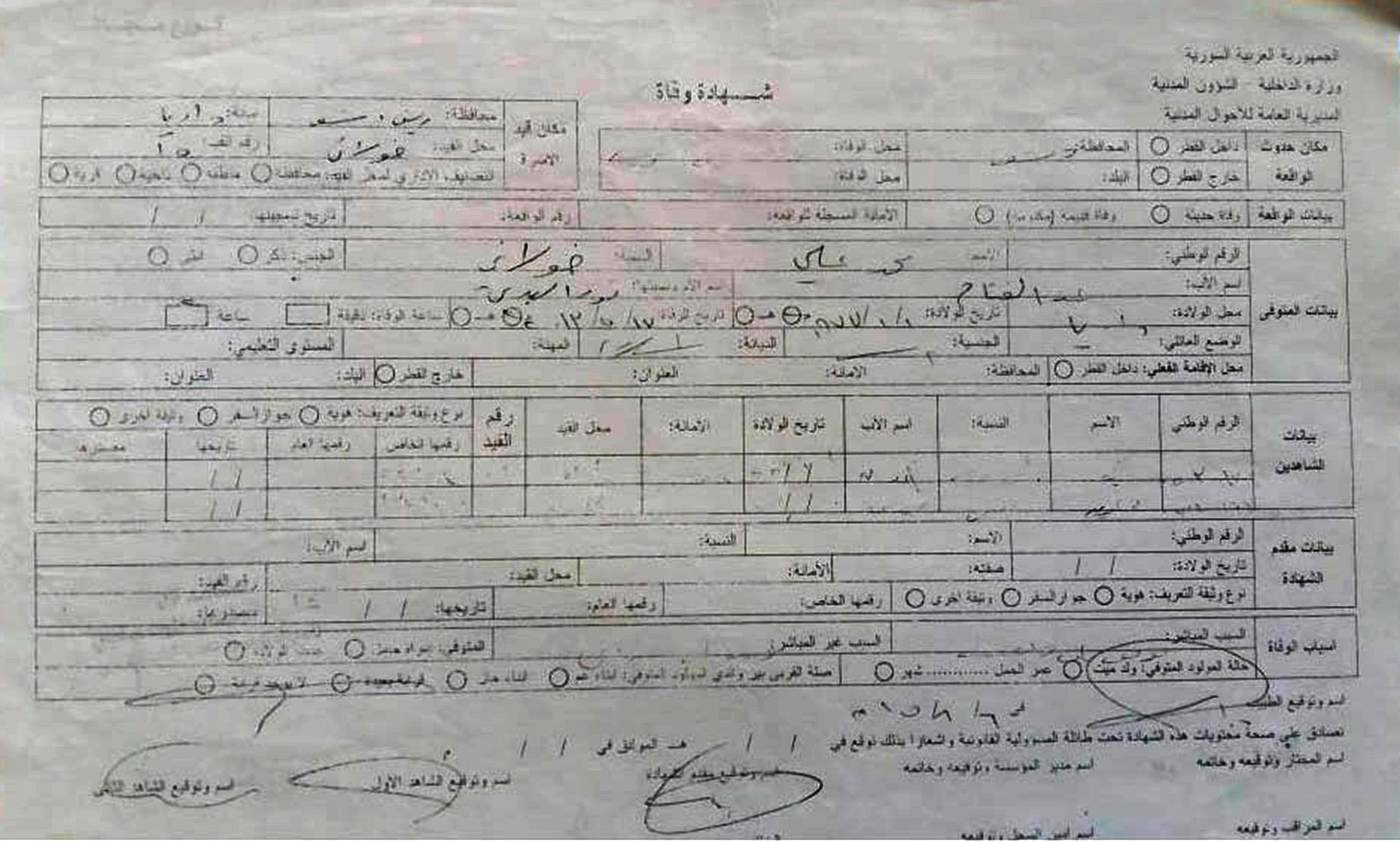

In a bid to hide its horrific crimes, in July the Syrian regime started informing people of the deaths of their loved ones, citing heart attacks or other natural causes. These “death notices” have been displayed in front of civic offices, where queues of people have stretched, desperate for news, waiting for hours.

The men and women who manage to survive detention give accounts of torture, summary executions, and sexual violence. Credible reports from civil society groups providing support to those released from detention have found that a majority – men and women alike – were victims of sexual violence, which leaves its own indelible psychological mark.

The UK has been working to shine a light on these atrocities. We co-hosted an event in the margins of the UN General Assembly last month to highlight the issue of detainees. We have used our position in the UN Security Council to raise the subject, and pressure the regime and its backers, Russia and Iran, to take action. We lead on the Syria resolutions at the UN Human Rights Council, including mandating the Commission of Inquiry to report authoritatively on the human rights situation in Syria. We co-sponsored the UN General Assembly resolution to create the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM) to document the most serious crimes committed in Syria, and have given £500,000 in funding towards the IIIM this financial year.

We have given over £8m to help survivors secure access to services and legal advice, to support alternative justice mechanisms and to fund efforts to document the regime’s brutality. And by working with allies, we have secured tough EU sanctions against over 300 individuals and entities responsible for the violent repression of civilians.

But no one except Syrians can truly speak for the Syrian people. Amina Khoulani, now living in the UK under our Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme, was detained in the early years of the uprising. Her story published here for the first time reminds us all that though the arc of justice is long, its urgency is felt by Syrians today.

Alistair Burt MP is minister of state for international development, and minister of state for the Middle East at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office

****************************

Amina Khoulani’s story

Before the civil war in Syria started, I lived in a small city called Darayya on the outskirts of Damascus, with my husband, children and other close family. I worked as a history teacher in a high school in the centre of Damascus, which I loved. And I was an activist with a huge passion for the protection of human rights. I always knew that Syria was controlled by an oppressive, brutal regime. Long before the uprising in 2011 the people of Syria had no human rights, no freedom of expression, and there was certainly no democracy in the country. Forced disappearances and detentions had been the norm since the days of Hafez Assad, who ruled before his son Bashar took over in July 2000.

I was part of a group of young men and women that was engaged in peaceful activism in Darayya. The group’s godfather was Abdul Akram al-Sakka, an enlightened preacher who adopted non-violence as his philosophy. In 2003, we organised campaigns addressing bribery and corruption, public initiatives to clean our streets, and protests not only about violations taking place in Syria but also about those taking place in other countries. We became known as the “Darayya Youth”.

As a result of these activities, we were summoned by the intelligence branch for interrogation. The women were interrogated every day for a full month from 9am until 5pm. At the time I had just had a baby, but I was still forced to go there with my baby in my hands to be questioned every day. The men who were part of “Darayya Youth”, including my husband and brother, were immediately detained and referred to military court. They were sentenced to four years in Sednaya prison, notorious for the torture and murder of prisoners. Prisoners rarely came out of Sednaya alive. When my husband was released and came home after a year, he was mentally sick with depression and physically sick with pneumonia.

Because I had been part of the protests, when the uprising started on 16 March 2011 I was called to the intelligence branch to sign a piece of paper promising not to participate in the demonstrations. But, for me, the uprising was a dream come true. It was a chance for the people of Syria to express to the government that we wanted democratic change and civil rights for all Syrians, regardless of race or religion. So I continued participating in the demonstrations.

My husband and I, and my brothers Majd and Abdulsatar, became more and more involved with the demonstrations, organising non-violent protests, handing out leaflets on the street and visiting the graves of protesters killed during demonstrations and their families to offer them bereavement counselling. My brother Majd came up with the idea of handing roses and water bottles to the regime guards attacking protesters, with a note saying: “You and I are Syrians, so why are you killing us?” This is the kind of person my brother was – sweet and peaceful. He was only a second-year law student, but he was already one of the leaders of the non-violent movement in our town.

It was after this protest that I experienced the depths of brutality within the regime’s detention system first hand. In July 2011, my brother Abdulsatar was detained by the regime’s air force intelligence. 15 days later they came back and arrested Majd. Both were transferred to Sednaya prison. Normally when people are detained by Bashar al-Assad’s regime they disappear and their families struggle to trace them. But we were lucky in a sense, as we were told by people who had been released that they had seen them in the prison.

Under the regime’s rule, those held in prison are not allowed visits, but my family and I tried everything we could think of just to see them. Eventually we obtained a visitor’s permit by paying bribes. We waited outside the prison for three hours before we were allowed to go in. It was really cold, as it always is in December in Syria, and I remember telling Majd’s children to jump up and down so that they didn’t freeze.

When the guards eventually let us in, we were treated in such a demeaning way, from the degrading body search to being insulted as we took the bus to the detention centre. In the detention centre, there was two nets separating us from the prisoners. We were told we could see each brother for 15 minutes, and we couldn’t ask them about anything except their health.

When Abdulsatar walked in, I didn’t him recognise him. I thought they had made a mistake and bought the wrong inmate. Then I heard his voice and I knew it was him. After 15 minutes, they took him away. We waited another hour to see Majd. When he was brought in, he was as confident and defiant as ever. My mother asked him: “Have you seen Abdulsatar?”, and the guards beat him in front of us because we weren’t allowed to ask that. It was heartbreaking. We weren’t allowed to comfort them and my brother wasn’t allowed to hold his children. Even so, because visits are so rarely allowed, people from our town came to congratulate us on seeing our brothers.

We were joined by all of the children and elderly people in our neighbourhood, all crammed in to a small, hot room, with no air-conditioning and one toilet between us. We had no electricity or telephones

On 20 August 2012 the Darayya massacre started. It lasted for six days. It was just after the Eid holiday. The regime blocked the access and exit routes to the city. It was then that the bombing started. They used mortars, missiles, all types of bombs – they didn’t care where they targeted. When the bombing first began, I took my family to the ground floor of our house thinking it would be for an hour, but it lasted for what felt like forever. My children were petrified. My youngest daughter wet herself from the fear.

We knew we had to find somewhere safe to shelter until the bombing stopped. As there were no bomb shelters in Darayya, we took shelter in the cellar of my neighbour’s house. We were joined by all of the children and elderly people in our neighbourhood, all crammed in to a small, hot room, with no air-conditioning and one toilet between us. We had no electricity or telephones. The toilet soon began to overflow. The sound of the bombing was so loud. We were living in the worst conditions that you could ever imagine. I will never forget how terrifying it was, but I had to stay calm and help those around me. I read stories to the children and gave them colouring books to relax. Two things about this time really stick in my mind: a woman in her twenties giving birth with no medical staff around to help her, and the moment when a dead boy was brought to his mother in the cellar so that she could say goodbye before he was buried. His mother was distraught. I couldn’t imagine how I would have felt if that was my child.

On the third day, the bombing calmed down. It was then that we were able to switch on the television using a generator. We found out that the regime had not only bombed from the sky, but had now entered the town by foot. Months before, we had heard that this had happened in other towns, with the regime killing innocent people including children. We were all scared that this would happen to us too. I tried to reassure people but in my heart, I was as terrified as they were.

When we heard that regime militia were streets away, we knew we could not wait and had to flee. I didn’t recognise Darayya when we came out of the cellar. It was like hell on earth, buried and destroyed, with bodies everywhere. It was far from the town that I knew.

We packed our family into our small car and left Darayya. I felt so guilty leaving behind those who didn’t have cars but we had no choice. We couldn’t use normal roads for fear of being stopped at check points so we drove across the orchards until we reached Damascus. When we arrived I finally felt safe, but it was also very painful. We had only travelled seven kilometres, and yet the people in Damascus were living their lives normally – going to work and school and listening to music. It was walking distance between the two towns, yet no one in Damascus was feeling the pain that we had all just experienced in Darayya.

We settled in to life in Damascus, but our second entanglement with the regime was still yet to come. The regime frequently stormed into random properties looking for young men to conscript in to the army. One day they came to our house and saw the IDs of my two brothers. When they realised that we were part of the Khoulani family that had joined the uprisings in Darayya, they took my other brothers Bilal and Mouhamed. Neither had anything to do with the protests, they just happened to be related to people who were. They were detained by the infamous 215 military intelligence branch.

After seven months, on 22 April 2013, Bilal was released: I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw him. He looked like a skeleton, a 100-year-old man waiting to die. But words cannot describe how happy I was to see him. It was then that he gave my sister and me the news that Mouhamed had been killed in front of him in prison. I hoped that he was wrong and that his troubled mental state had made him confused, but deep inside I knew he was telling the truth. I couldn’t tell my parents or mourn in front of them – it would have killed them. It was only when the regime’s photographer, “Caesar”, defected and published pictures of those that had died in custody and we saw a picture of Mouhamed that our hope faded, and we told my parents and Mouhamed’s wife. The military police told us that he died from a stroke. When he was taken, his wife was pregnant. He didn’t know his son, and his son will never know what a great person he was.

When we were menstruating we weren’t allowed any dignity and guards refused to allow us access to sanitary products. We had to use torn up rags and clothes. That was torture in itself

This made my family even more anxious for the safety of my other brothers Abdulsatar and Majd, who were still in detention. We spoke to everyone we could to obtain news about them. We harassed the police and asked other people who had been detained. Eventually we were told that they were killed in a field execution, just like all of the other innocent people who participated in the peaceful demonstration handing out flowers. Again, I refused to believe it; to me it was “fake news”. My brothers were not just my family, they were my friends. Majd was like my own baby. As he was the youngest, and I was the oldest, I had taken him to school and bought him clothes. I did for him as I did for my own children.

In October 2013, the air force intelligence of Bashar al-Assad’s regime raided our house again, but this time looking for me. One morning, whilst still in my nightclothes I heard a knock at the door, I opened it and eight people marched in, guns by their sides. They asked me my name and, when I told them, they said: “We’ve found her.” My daughter was in her pink pyjamas hanging on to my legs, crying, when they were trying to take me. I refused to go until they let me get dressed. When they took me outside, I saw my husband in one of the cars. They had arrested him too.

This is when my own journey into the detention system really began. They put me in solitary confinement in a tiny cell, for what I think was a day. It was only about two metres long by one metre wide. The next day they bought more women in there, until there were 13 of us. We had one broken bathroom between all of us, with bugs and cockroaches crawling out of it. We had to use boxes or plastic bags to go to the toilet. When we were menstruating we weren’t allowed any dignity and guards refused to allow us access to sanitary products. We had to use torn up rags and clothes. That was torture in itself. The food was terrible: small quantities of rice, bulger or potatoes. The rice had small stones in it and tasted like diesel.

One day the guard was taking me down for interrogation, all the way cursing me and using insulting sexual references. I started crying but they continued. When the lead interrogator asked me why I was crying, he laughed and started calling me names too. He wanted to make sure that I lost any humility and dignity that I had left. I was one of the lucky women in that I was not subjected to sexual violence, but I heard the stories of the women who had been.

The torture techniques used almost made me have a breakdown. On one occasion, they took my husband and me into a room, blindfolded us and made us both face a wall. They loaded their guns and pulled the trigger. A fake execution. I was in shock. It took us a few minutes to realise that we were still alive. This kind of torture was relentless.

One day, they tried to force me to confess to crimes I hadn’t committed. I refused. They cut and slapped me but I was firm in my denial. After some time, one of them asked me if I loved my husband; of course I said yes. It was then that they bought him in the room. He was in his underwear and looked like he had been in prison for a million years – he was so thin. They beat him until I agreed to confess to all of the crimes that they accused me of. Until this day, I don’t know what I signed, I just wanted to them to stop. My husband and I were sentenced to four years in prison.

After six months I was released. I am not sure why, but I think it was because my family paid guards to release me. Shortly after, I left to Lebanon. I didn’t want to leave my husband alone in prison, but for my children I had no other choice – I had heard rumours that the intelligence were coming to arrest me again. Sometime later my husband was released and joined us.

I came to the United Kingdom in early 2018. Whilst I made friends and have truly been welcomed by the people of the UK, the internal scars of this experience have not healed.

This year, I received notice that Majd and Abdulsatar had been killed in detention, with the document saying they died at the very same time on the very same day on the 15 January 2013. They had been executed. I was devastated. The Assad regime gave us no reasons as to why their lives were taken.

When I learned of their deaths through the death notices, I felt like I wanted to end my activism work and stay silent. I could not grasp that such massacres were being committed by the regime of Bashar al-Assad while the world watches on. But over time, I have begun to realise that I cannot let my brothers die in vain. They fought for what they believed in and it is my job to keep their memories alive. I want everyone to know what this regime is like. They are a lying, murderous regime. Under Bashar al-Assad the people of Syria will never have human rights, no civil rights and women will certainly have no rights at all. Human rights are a joke to this regime. It’s something they do not understand. The words are not in even their dictionaries.

I will continue to tell the story of what they have done to my family and the people of Syria. The international community and the people of Syria must never ever let the regime forget what they have done and not pay for the crimes that they have committed against us. Assad is no different to other dictators or war criminals, and history has shown that dictators face the consequences of their actions. I believe one day Assad will face justice too, and until this day comes I will not stop my struggle.